“Go Fly Yourself”: Marketing ‘Sex’ and the Great Stewardess Rebellion — An Interview with Nell McShane Wulfhart

Citations Needed | June 14, 2023 | Transcript

[Music]

Intro: This is Citations Needed with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson.

Nima Shirazi: Welcome to Citations Needed, a podcast on the media power PR and the history of bullshit. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam Johnson: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: Thank you, everyone, for joining us tonight for a live interview on Citations Needed. Of course, you can follow the show on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed, and if you are not already supporting the show, you can do that through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast. All your support through Patreon is so incredibly appreciated as we are 100% listener funded.

Adam: Yes, and as always, if you sign up to our Patreon, you can get access to over 130 News briefs for patrons that we’ve done throughout the years, show notes, live shows and events such as this one and other kinds of goodies. And of course, you can help keep the show itself, the episodes themselves free, which we’ve been doing now going on almost six years and your support has helped make that possible.

Nima: For this Citations Needed interview, we are so lucky and thrilled to be joined by journalist and author Nell McShane Wulfhart, whose book The Great Stewardess Rebellion: How Women Launched a Workplace Revolution at 30,000 Feet was published by Doubleday last year, and is already out on paperback and you should all pick that up if you don’t already have it. That book is the topic of tonight’s interview. And we are so happy to be joined by Nell, who is coming to us live from Uruguay, where you are based. Hi, Nell, how you doing? Thanks for joining us.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Hey, thank you so much. I’m excited to be here.

Adam: So on this show, we’re going to do something a little bit different than our usual format, which is, Nell is going to is going to do a little bit of a presentation based on her book and her research to help us kind of guide through this with visuals and other markers. So without further ado, I want to throw it over to Nell to sort of start the presentation we’re going to we’re going to do this and then we’re going to discuss afterwards. So it should be very interesting. So, now you want to go and take over or take it away.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Sure. Sounds great. I’m super excited to be here and talk about this unheralded part of labor history that’s all about flight attendants. So, when you think about the 1960s, like the golden age of travel, this is probably more or less what it looks like, right?

It’s glamor, drinks, cocktails in first class, somebody slicing filet mignon for you, real silverware, and stewardesses who are slim and conventionally attractive, wearing short skirts and always smiling. And this is the truth. This is actually how it was. Now, to become that stewardess and to live this incredibly glamorous looking lifestyle. It was just a really aspirational job. There was a newspaper ad from 1961 that recruited women to work for American Airlines by saying this morning sightseeing in New York, and in about five hours meet my date for dinner in San Francisco.

So, it painted this really attractive picture for young women who are in small towns or on farms or in cities all over America. The other available jobs are mostly things like becoming a teacher or a nurse or maybe a man’s secretary. So you can see that when the alternative was putting out a designer uniform jet setting around the country or the world and meeting people like Don Draper. You can see how appealing that might have been.

This shows you how hard this job was to get. There was a saying that it was easier to get into Harvard than it was to get a job as a stewardess at TWA. And this exclusivity only added to the glamor.

We’re looking here at an ad for Eastern Airlines and it’s called, “Presenting the Losers.” The copy reads,

Pretty good, aren’t they? We admit it, and they’re probably good enough to get a job practically anywhere they want. But not as an Eastern airline stewardess. We pass up around 19 girls before we get one that qualifies, it looks for everything. It wouldn’t be so tough. Sure, we want her to be pretty, don’t you? That’s why we look at her face, her makeup, her complexion, her figure, her weight, her legs, her grooming, her nails, and her hair.

They go on to list a lot more stuff. But you can see how stringent just the appearance qualifications were. And 19 applicants were rejected for everyone that they accepted. This was truly an exclusive club. You might also notice some uniformity among the women in this picture. For those of you who are listening, they’re all white. And there were some more very specific requirements for getting a job as a stewardess.

Here are some questions to get a job as a stewardess. You had to be unmarried, be childless, have straight teeth. have clear skin be under the age of 30 to have perfect eyesight, be at least five feet two inches tall, but be under five feet nine inches tall, weigh less than 135 pounds and have no visible scars. These are all real requirements and the 135 pound weight limit by the way, it was for the very tallest women. When a stewardess was hired, she was measured, and her height determined the maximum weight she was allowed to reach. They had a whole chart for this.

And if she went over her maximum weight, even by a couple pounds, she can be pulled right off a flight or even fired. And it shouldn’t go without saying that you pretty much always had to be white. And once they get the job and they graduate from stewardess Training College — at American Airlines, a stewardess Training College was known as the charm farm — now they’re prepped and they’re ready to go, but they’re not going to be flying for very long. That’s because they’d be fired. If they got married. They’d be fired if they got pregnant. And if they managed to avoid both of those things, they’d be fired when they turned 32 years old. This ad reads “Old Maid” and the copy says:

That’s what the other United Airlines stewardesses call her because she’s been flying for almost three years now.

The average tenure of United stewardess is only 21 months before she gets married. This ad goes on to talk about how United stewardesses can serve dinner to dozens of people at once smiling the whole time.

And the tagline reads:

Everyone gets warmth, friendliness and extra care, and someone may get a wife.

Now, it’s true that most stewardesses got married. Within a few years, there was a huge amount of turnover, which of course benefited the airlines. Not only did it keep the stewardesses looking very useful, but they didn’t spend time fighting for things like better benefits or pay or pensions when they knew they’d only be working for a little while. Now, of course not everyone thought that being a flight attendant was just a temporary job filling in the time between high school and college and getting married, but there wasn’t really anything they could do about it. Then in 1964, the Civil Rights Act is passed. And this includes Title VII. This states that employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin is now illegal. And the airline stewardesses suddenly see a way to get rid of all those rules about getting fired when they get married, when they turn 32 Or when they get pregnant.

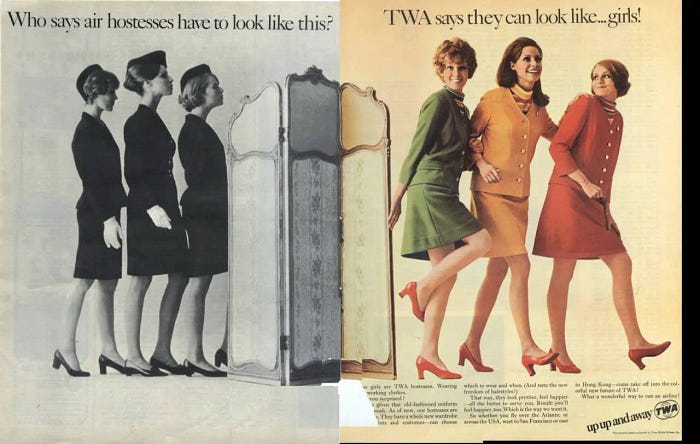

So, the main point of Title VII from the perspective of the lawmakers is to try to fix racism and employment. virtually nobody anticipates that anyone’s going to use it to work on sexism. Except for stewardesses. They start showering the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission with complaints. And then they hold a hearing at the EEOC trying to get the airlines to hire men as stewards. They reason that if men start working in the cabin, thanks to Title VII, firing women when they got married or they turned 32 would become illegal. Of course, the airlines want to keep the job exclusively for young women. You can see from this ad how the airlines created the image of the perfect stewardess if that woman was married or pregnant or old, the illusion that her only function was to cater to the male passenger would be destroyed.

And in 1968, after several years, the EEOC decides in favor of the stewardesses. Rules about marriage and age have to disappear and men can start working as flight attendants.

But it’s not that easy. Of course, the airlines fight back. They do not want to have to hire men. They don’t want to have to keep women working beyond the age of 32. And they don’t want to ruin the illusion that all of their stewardesses are single. More court cases follow this as the flight attendants take each airline to court to make it comply with the law. Now this take years and there are setback after setback, but the stewardess court cases around marriage and age become the basis for case law against sex discrimination. And in the years that follow, those stewardess cases will be used as precedent to inequality for women in the workplace. And actually many of the rights that American working women have now can be traced directly back to the stewardesses. Now, as these women start to gain more rights in the workplace and turn a job into a career, we start to see the airlines making a change in their ads.

“The Airstrip” is the first one in the mid 1960s. And this was from Braniff Airways. This was a real thing. The stewardesses would board the plane wearing Emilio Pucci designed uniforms in several layers. And as the flight went on, they would gradually begin to remove some of these items of clothing. It didn’t get too racy, but the definitely the innuendo was there and all the ads and you can sort of see that this starts the sexualization of flight attendants, right? They’re less caretakers now and now they’re sex objects in the sky.

This sexualization of stewardesses really hits its peak on this next slide with the “Fly Me” campaign. So this was a 1972 campaign run by national airlines, and it featured pictures of real working stewardesses. There’s a woman in this photo, her name really is Cheryl, and the copy reads:

I’m Cheryl. Fly me.

Now the airlines went so far as to paint the names of the stewardesses on the outside of the plane. So you could be on the ground and you could literally like watch Cheryl fly by or you could literally fly Donna or whomever it is. And this campaign is not pulling any punches, right? This is like extremely obvious what they’re trying to say here. Look, you can see “I’m Laura. Fly me nonstop to Miami.”

And then the next one is Cheryl again. “Millions of people flew me last year.”

As you can imagine, the stewardesses hate these ads, they complain to national airlines, nothing happens. They’re already having a hard time getting taken seriously by either their employers or the passengers. And these ads are everywhere. There are Fly Me t-shirts, there are Fly Me coffee mugs. There’s a Fly Me jingle. Everybody knows this campaign. So, stewardesses go out there and they pick it like crazy. One of my favorite signs from their picketing was a big one that said, “Go fly yourself.”

And they made headlines because angry stewardesses is a really good news hook. But they’re starting to realize that the only way that they’re going to make real change is through the union. Now, flight attendants are unionized. And they always have been at almost every airline, but they’re affiliated to much bigger unions like the Transport Workers Union or the pilots union. And the union leadership tends to treat them in the same way as the company executives do. Like these women are mascots, they’re not workers. They’re not workers in the same way that a mechanic as a worker or a pilot, as a worker, or the person who cleans airplane is a worker. And the union leadership is making all the decisions for these women. When it comes to sexist ads like Fly Me, they don’t care and they do nothing. Now, this is far from the only issue that the stewardesses have with the union leadership, but it’s definitely the most visible one. So, in the 1970s, they make a change. Tens of thousands of flight attendants break away from male-run big labor federations and pilots’ unions, they break off and they form their own unions. These have names like the Association of Professional flight attendants, and the use of the word professional in there is not an accident. These new unions are led by women and they begin negotiating directly with the airlines. Now, this is really a big moment in labor history. And the flight attendants, it’s important to point out are not leaving labor. They are not questioning that necessity for unions, but they are making sure that is working for every one of them. It isn’t really about representation. Big labor doesn’t want to represent them. They’ll represent themselves. And these are some of the very first women-led unions in the United States. You can see a sign here from Delta Airlines.

These actions I’m talking about now happened in the 1970s, but flight attendants today are still a really powerful force in the labor movement. There’s only one major airline in the United States where flight attendants have never been unionized, Delta Airlines, they have a long, proud history of union busting, as you can see from the image. But there is a big vote coming up this year and more than 20,000 Delta flight attendants will vote on whether or not to unionize. That campaign is being led by this woman. I’m sure some of you are familiar with her. This is Sarah Nelson.

She’s the president of the Association of flight attendants, which is a union of around 70,000 people. And she’s kind of the natural culmination of the flight attendant tradition of union organizing and communal work. She’s one of the most powerful people in labor right now. And she was a United Airlines flight attendant. So looking at Sarah and thinking about the story of the stewardesses past and present is really a great reminder that feminism and labor are inextricably intertwined, that women can’t succeed without unions, and the unions can’t succeed without limit. So that is it from me.

Nima: That is so awesome. Now, thank you so much for walking us through that.

Adam: Yeah. Again, thank you for that, that was wonderful. Um, I want to I want to sort of begin to focus the discussion in about the book in your presentation, by talking about the advertising industry in popular depictions and media that sort of sold as you as you note in detail, so excruciatingly, the, the flight attendants is kind of sexualized objects and as you also know, kind of, quote, wife and wife and training, right, this sort of supposed to be training wives, the general idea is that if you fly with us, you could, the women will be sexually available, there’ll be someone you could propose to, at some point and or, you know, whatever be with us actually, both for both for the people who work at the airline, their bosses, and also, of course, the consumers. Now, I want to sort of talk about just generally how that was used to kind of achieve product infringe differentiation, but also I want to talk about the kind of romantic depictions of 1960s flight, both in pop culture contemporaneously at the time, but also in retrospect, we’ve seen this trope and many you know, movies and film I it’s not really seen as in credit, it’s not really done critically, but some exceptions. I know there was a show TWA guy used to wait tables with was on it. That was maybe a little more critical of this. But also kind of a movie catchphrase.

Nima: The movie Catch Me If You Can does like the opposite of that.

Adam: Of course. And can you talk about how like this sort of swinging trope of where everyone’s kind of sexually available maybe sort of obscures that this was not a choice for a lot of people?

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Oh, sure. I mean, even when I was researching this book, just Googling things about flight attendant turned up so much pornography, like there is just such an established idea of flight attendants as sex objects that you know, I detail in the book, and as you could tell from the presentation, I did that, like, even when I had the idea for the book, I was like, Okay, it’s about labor. It’s about feminism. And it’s about stewardesses. And I just knew that was like a good hook. Because we do have this sort of association even with the word stewardess of yes, this swinging ’60s of sexual availability. And there’s definitely an idea that like these women were flying from, you know, they had a man in every airport, you know, that they were like, really sexually available. They were living these glamorous, glamorous lives. And that is honestly a construction of the airlines. Adam, you were asking how the airlines use these ads to sort of differentiate themselves from other airlines?

Adam: Yeah, because they’re going after a largely male audience. And I mean, again, I don’t think, we could clone 10,000 Freuds and I don’t think they could begin to unpack some of these ads, right. Like there’s this is, there’s such a weird combination of sexuality, but also motherhood and or both in the same ad. And it’s like we got there’s definitely some issues going on here. And I’m, again, I’m sure half of these people on Madison Avenue were Freudians.

Nima: The caretaking and the constant service, right.

Adam: Yeah.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Yeah. I mean, you can really see the evolution of it. And there’s tons more of these ads in the book. But like in the ’60s, it’s all about like special care. And the images are of these women like straightening amounts ties, he gets on the plane and, and welcoming them with a big smile on her face. You know, they’re these men are 40 years older than her. And then as we get into the ’70s, and they’re sort of like the sexual revolution, it goes the other way entirely. And these are literally like flying Playboy Bunnies. And airlines, yeah, they they lean really heavily on this, because there’s a point at which, you know, they were all flying to the same places, and the prices were set by the government. And there wasn’t that much to distinguish between the airlines except for the stewardesses. And there was also some sort of well known ideas among among the women who were applying for the job that like, each airline had a type. So if you were sort of a Girl Next Door type, American Airlines was a good fit for you. If you were maybe more curvaceous and a little more sexy, then maybe United Airlines would be more likely to hire you. And then we also get into like the crazy uniforms that they put these women in which get more and more interesting, I guess, as the years go on, but this was truly just a marketing strategy. Like that was what they were selling tickets on.

Adam: I have a somewhat tangential follow up. One theme I’m interested in which we’ve I don’t know if you’ve really got into in the show is I feel like you saw this with a lot of these retrospectives when Hugh Hefner died. Where there was this conflation, I think sometime around the late ’60s with women’s liberation with like sexual objects, objectifying from patriarchal systems that were not owned by women were not run by women, but were only run by men. That was somehow liberatory in and of itself, and you saw you saw that with a sort of the more racy ads in the ’70s, that it was like, somehow feminist to sort of be an object. And I don’t wanna get too much into feminist theory here, because it’s certainly out of my pay grade. But I’m sort of curious if you want to touch on that a little bit, because I definitely there’s definitely some, the whole swinging ’60s thing and then the ’70s. It sort of plays into this idea that like, Oh, they’re just being free, but then you read these testimonials and you see this stuff and you’re like, oh, wait, no, this is me to the extent to which it’s it’s a very kind of libertarian, rose-tinted, you know, perspective, I think.

Nima: But it’s also really interesting that, like, once the strength of a union started to be realized, the ads went from like, gross to lurid. I mean, like, the airlines reacted in a way that you thought things would kind of get tempered and they actually got ramped up.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Yeah, the airlines, you could definitely see how like, the more right through it, the stewardesses started winning in the workplace, the more the airlines, sexualized them in the ads and really, like controlled them that way. And when we think about sure, like the ’60s and the ’70s, as a time of sexual liberation, absolutely. But it’s certainly one thing to feel sexually liberated yourself, and another to be told that you’re, like, a flying sex object.

Adam: Yeah, there’s a conflation of those two things.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Totally. And some of the stories that the women told me were, were not so much about like their own sexuality and their expression of that, which was something totally different. It was the fact that these ads were losing them respect. You know, there was a woman who was told me that her husband’s friends all thought it was really titillating that he married a stewardess and people would make jokes about them. And if they wore the uniform on the subway, people would cat-call like, that mean any stories that get much worse than that, but there was just a general like, lack of respect towards the profession entirely. And that was thanks in no small part to those ads.

Nima: Yeah, you know, the story of frustration and fury and then like support and solidarity, the move from labor organizing to real unionizing, right is told throughout this book in amazing detail and research and also like great anecdotes throughout. And I’d love to hear a little bit more about this trajectory and you and you mentioned it in your in your, in your presentation, but just to dig a little deeper into this trajectory from stewardesses initially being members, right of a larger union, right like being part of the Airline Stewards and Stewardesses Association, which is an affiliate of the Transit Workers Union, that TWU, but then how the advent and rise of the Stewardesses for Women’s Rights organization, the SFWR, led them to the creation as he said of the new union, are you one of them, you know, a number of them, the Association of Professional flight attendants, right and you can even see out the language shift is so deliberate, as you said. So, how now is the story of unionization also a story of necessity breeding innovation and this subsequent independence of these women-led unions?

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Sure, well, they do start out affiliated to the Transport Workers Union part of a much larger union. And eventually each airline gets their own local, so American Airlines stewardesses were Local 552 Transport Workers Union and United Stewardesses were something else. I mean, the whole thing is very complicated. And I would say a little bit boring to describe how they got to that point.

Nima: Our listeners love boring.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: (Laughs.) Well, they can get they can read the book if they want more detail. But um, there are basically a number of different unions, each airline there stewardesses are in their own union. And they’re usually affiliated to either a big male run union, like the Transport Workers or to a pilots union that makes all the decisions for them. But either way, the people who are negotiating at the bargaining table who are talking to the company leadership, these are men, the intermediator, engineer intermediaries, excuse me, and they are not really listening to what the women are wanting. Like there’s a great story in the book about how, at one point all the stewardesses and American Airlines want is single rooms on layovers, right. Like this was an issue where pilots always got single rooms at the hotel and the layover, and now that they had started hiring men, the men always got single rooms at the hotel on layovers, but the stewardesses always had to share. And this is kind of, I think, one of those classic labor things were like the things that workers are mad, the thing that workers are mad about is not the thing that the public thinks is important, or in this case, what the TWU people thought were important. And there was sort of an epic showdown over the single room thing. I mean, it was a strike issue, like there was a huge, a huge thing. And it was essentially because the the greater leadership, the big labor leaders, were not listening to what the actual workers wanted. And part of that is course like they were women. And like they were not really workers. And the Stewardesses for Women’s Rights, which actually, if you’re watching, you can see behind me, I have my sign up there. This is their real logo, which is, like beautifully Seventies. And this was a group, it was not a union. This was a group that never had more than 1,500 members. And it only existed from 1972 to maybe 1976.

Just Stewardesses for Women’s Rights, a small group that got a huge amount of press, calling attention to the issues that the union leadership was ignoring. Gloria Steinem was a huge supporter of theirs, she would turn up at their meetings in this little church in the village, they just got like an outsized amount of attention for what they actually were like a tiny group. And they were not a union, even though the Transport Workers tended to treat them as a threatening union and really wanted to destroy this group. But they managed to call enough attention to these issues that, you know, people really started to pay attention and to notice things like, you know, the sexist ads.

Adam: I want to talk a little bit about the way in which the sexism also was cultural, obviously, for obvious reasons, and was a marketing gimmick for obvious reasons. But also really was very convenient from an anti/labor standpoint, where if you have these phase fade outs at 32, if you have all this precarity, weight gain, you basically create a very transient, or a very transitional workforce, similar to what a lot of employers do, right, for various reasons. And they talk about the kind of all the people who apply for them, right? Walmart does this all the time, Walmart say, we’ll just use the same line, we’re harder to get into than Harvard, I think that’s bullshit, for the most part. And I actually would be curious to the extent to which that was actually true for the airlines. I imagine, it probably was somewhat competitive. But you know, they have a tendency to inflate those things to add glamor to it, right, just as colleges do. But that idea that like, you’re lucky to be here, to the extent to which you’re here, you’re going to be here for a very short period of time, again, obviously works very well when you’re trying to make labor weak and precarious. And divided. So I want to talk about the ways in which like you said, the sort of sexism was baked into the cake of anti-labor practices and how they reinforced it and how did those women kind of overcome that because it is true that that is anyone who’s ever tried to unionize a restaurant knows right sort of people are there for six months, nine months, they’re in and out, the more they built, they build in transient this to the job, the harder to unionize. So how did they overcome that? What were the ways they push back against that? I imagine getting rid of some of these criteria for these horrific criteria for being fired was one way they did it to get a little more stability. Can you kind of talk about that? And how the fight against these, these sexist barriers were also at the same time a fight for more labor security?

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Yeah, sure. And I think the point about, you know, like workers and restaurants, kind of having jobs for a short amount of time is relevant. And when you think about, you know, trying to unionize or to get communal action, collective action for a group of people that are constantly on the move, like they’re based all over the country, they work for the same company, but they’re in bases all over the country, and they’re constantly flying from place to place like just the logistics of it, especially back in the ’70s are mind-boggling.

Adam: There’s no Signal chat for that.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: (Laughs.) I’ve looked through archives of like so many handwritten letters that people were sending to each other, usually on hotel stationery, you know, they’re writing from their layover in Des Moines or, or wherever. But yeah, I mean, the whole idea of sexism as a, I mean, it’s a classic way of dividing the workers, right? Like you have them segregated. If they’re in the same union as the pilots and they’re all in it together, things start to look a lot different. But the pilots are all men, they make three times as much as the stewardesses do they have job security. And when you have them sort of cordoned off and their own locals, not even with other stewardesses in the one union, I mean, it becomes becomes a real issue. And then you further sort of winnow the crowd and suck away power by putting an age restriction in putting a marriage restriction in putting a pregnancy restriction and putting a weight restriction in. And of course, that sows division among the workers, I mean, there were plenty of flight attendants who thought that these weight limits and again, these weight limits were like stringent like you had to be very slim and remains limp to be a flight attendant, like they were really tough. Half of them were hopped up on speed, and I’m not even really exaggerating, or just by like a tiny amount, which, of course, terrifying. And, and so even within the ranks of the stewardesses, you have like, oh, well, like some of the stewardesses thought the weight limits made sense and somebody even used the term, ‘Yeah, we need to get the fatties out.’ Like, you know, there’s plenty you know, the you create a hierarchy, you know, and that comes that comes from the company down it doesn’t come for the workers up.

Adam: I’d be remiss not to ask about the intersection of this with race because what you know that this is obviously a very white feminist enterprise here. So I am curious to know from your book when they when they did begin some kind of integration to the system. How would you grade the union’s approach to that? Again, I know it’s a different time. But what did that look like? And how did the issue of basically having racial criteria as well make unionization that much harder?

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Oh, my gosh, the black women I talked to would tell me stories of being at, you know, the stewardess Training College, the charm farm. And they were given like pantyhose that was not the color of their skin, hair products they couldn’t use, makeup that looked like clown makeup. Like that was just where it began. This is like when integration was starting. And they hired a few black women as flight attendants. And then you know, the other flight attendants also exhibited, you know, same racism. Like I said, they had to share rooms on layovers. And a lot of the time, if a white stewardess was paired with a black stewardess, she would like race to use the bathroom first, so she wouldn’t have to use it after the black woman used it. Things like that, like so many stories like this, like really depressing. And I have tried very hard to see if I could find more women of color in the unions as this was happening, like who are actually taking action. But what a lot of women of color that I interviewed told me was that if they had been lighter skinned, they would have felt more welcome that this really was sort of like a white feminist enterprise. And yeah, certainly some of that is of the time, but they, there was not a lot of representation. Let’s put it that way.

Nima: Yeah, you tell this one amazing anecdote in the book, Nell, of you know, it’s wrapped up into obviously, sexism and racism, but also this division between pilots and stewardesses, right, who’s kind of at the front of the plane, who’s who’s in the back of the plane, where a pilot like comes over the speaker and asks, the stewardess is like, hey, when we, you know, touchdown, like, we’re all going to, we’re all going to go to some like meeting and you’re all welcome to join us. And then so, you know, so like, where are your good clothes, and they all like meet, like in the lobby hotel, and the pilot realizes that one of the stewardesses is black. And they’re like, oh, nevermind, and it’s because they were inviting the stewardesses to the John Birch Society meeting. And like, so even just the, the idea that, you know, oh, that’s like, that’s what the pilots were up to, like, on their lay overs. Do I mean, like, going to those meetings and then wanting to like, bring along their, like, arm candy coworkers, and then how that’s wrapped up into, like, their own politics and, and obviously, the politics of the flight attendants themselves and how those kind of butted up against each other?

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Totally. I mean, so many of these women told me that it was the Republicans in the cockpit and the Democrats in the cabin. And that didn’t really seem to be true. But a lot of the pilots, you know, there were ex-military. You know, they fly in the military than they then they get a job in the commercial airlines, they will definitely have a certain type. Let’s put it that way. And yeah, it was it was it was pretty depressing. I mean, all these stories were, were really horrifying.

Nima: You know, one other story you recount in the book is how the Stewardesses for Women’s Rights fought against harms and like dangers in the workplace. Airlines would frequently transport hazardous materials. And you write this:

“In 1973, one out of every 10 planes carried radioactive cargo. And it was estimated that an astounding 90% of this cargo was improperly packaged, thus exposing crew and passengers to high doses of radiation.”

So, can you tell us more about like this particular episode? What happened because of this? And also, you know, you know, maybe some other instances of how organized flight attendants work to change federal safety regulations for definitely the better?

Adam: That definitely explains why my parents were so weird, but go ahead.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Yes, that’s why I have this little tic now. Yeah, it was this was really horrifying to learn about and again, like this radioactive cargo, it was mostly for medical use, and the transport of it was mandated by the government, but the airlines got paid to transport it. And they ended up finding out that the you know, the FAA was kind of in cahoots and didn’t care about the passengers, was not worried about the safety of the people on the plane, and especially the people working the plane who are in the air, maybe eight hours a day, you know, being exposed to this, this radioactive cargo. And this is like the first time that Ralph Nader pops into the book. I did not expect to have to read so much about Ralph Nader when I was learning about flight attendants, but he becomes super concerned about this radioactive cargo. He carries little Geiger counter around with him to measure it. And the Stewardesses for Women’s Rights group I met — remember, this is only like 1,500 at its largest point, but these are very active stewardesses — and they work with Ralph Nader’s organization, and they form a group called, I think it’s called Safe Transportation of People. So stop, to basically fight against this, like improperly packaged cargo. And they do what they did for the sexist ads, they do informational picketing. They get out there, they get an incredible amount of press. And eventually they make a change. And airlines have to stop doing this. Like, it is literally like grassroots action that they take. And it was it was really effective. And yes, flight attendants kind of have a tradition of this, the first federal smoking ban in the United States was on airplanes. And that was a we know the work of flight attendants who are like, I mean, I’m old enough to remember sitting in the smoking section of an airplane with my dad, just like watching the smoke, you know, billow up above, but if you imagine, like working in those conditions for however many hours a day, you know, it takes its toll. So they definitely they took a lot of action in regards to safety.

Adam: So, the stewardess movement for women’s rights, I imagine they were obviously retaliated against quite a bit. I would think they had a big target on their back. I assume there was a lot of reaction to that. What were some of the ways in which they would retaliate? What were some of the ways that they would have media counter messaging? Did the airlines, because I’m trying to put into chronology when the airlines were deregulated? So maybe that was what, was under Carter, right, like in the late ‘70s .

Nell McShane Wulfhart: That was ‘78.

Adam: ‘78, yeah. What were some of the ways they they they push back against this union? Because the Empire always, of course, Strikes Back. So can you talk about that?

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Well, the Transport Workers Union which is you know, the airline to which the stewardess is in my book, at least were affiliated. They hated Stewardesses for Women’s Rights. And they while this the stewardesses weren’t like, they were not affiliated to a particular airline. They were not a union, but they were getting an incredible amount of attention. Somebody even gave them, for sort of a very small sum, an office in 30 Rockefeller Center, like they were they were really like calling a lot of attention to themselves and the airline or the Transport Workers leadership first of all killed accused them of dual unionism, and threatened to like expel these women who belonged to the group from the Transport Workers Union, which is a very serious threat. And there was another scene a very dramatic scene in which one of the leaders from the Stewardesses for Women’s Rights group. Her name was Tommie [Hutto], she’s kind of one of the heroines heroines of my book. She’s in a big meeting and the vice president of the Transport Workers gets up and he starts talking about Stewardesses for Women’s Rights. And he gets so angry and he’s like, ‘I want her out of here. These are dual unionists.’ He’s like spitting everywhere. And he starts pointing at her and says in the 1950s, we got rid of the commies and now we’re gonna get rid of the feminists. And okay, it’s true. The Transport Workers Union did have a Communist purge in the 1950s. But just the fact that he was so threatened by this group of 1,500 stewardesses and the headlines they were getting, I think, says a lot about like the outsized amount of power that they had.

Adam: Was Jane Fonda involved? Because I remember Jane Fonda was very much involved with secretaries’ unions in the mid ‘70s. That was the entire basis of “Nine to Five,” the Dolly Parton film. I think she even made it at their request.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: I wish, I wish.

Adam: Because she’s always good. She’s always good for it.

Nima: You just, unfortunately, you just had Ralph Nader and Jimmy Hoffa pop up. No Jane Fonda.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Yes, yeah, and Gloria Steinem. There’s a lot of famous people who end up in the book, but not Jane Fonda.

Adam: I feel like she always pops up in these stories. They’re like, ‘Yeah, and then we were about to close down and Jane Fonda gave us $10,000.’ Fuck yeah, Jane Fonda shows up!

Nima: And then Donald Sutherland shows up.

Adam: I was reading a story earlier about the secretary strike, which had a lot of parallels, 1973 in Boston, where they all the secretaries just stopped working for their scumbag bosses, because they were constantly being sexually harassed. And I was just curious if there was any connection there? Or if I mean, I get I’m sure there were in discussions, those two unions.

Nima: Maybe secretly bankrolled.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: I think the main connection is that they were like women-led unions, and like, the only are like, really the first women-led unions for sure.

Nima: Yeah, you know, you mentioned Tommie Hutto, I believe? And can you just tell us a bit more about, you know, these kind of two main characters that you kind of follow through through the book? The other one being Pat Gibbs, you know, they, you right, that they kind of approached their organizing tactics and their and their, you know, power building in very different ways. I mean, they were definitely allies, but definitely, but definitely in different ways. Can you tell us a little bit more about them, because you write so wonderfully about them in the book.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Yeah, thank you for mentioning that. Because people always talk about how well-researched the book is, but I want to talk about how much how many great character stories are really in there. Yeah, so Tommie Hutto Blake was a flight attendant who started working for American Airlines in 1970. She’s kind of a social justice warrior. You know, she, she she was always interested in social justice. She never imagined she’d be a stewardess for that long. But she was 60 something by the time that she retired, and she is absolutely like she becomes a leader in the stewardess union. She is a peacemaker, a deal maker, somebody who was like really interested in worker power, but through collective action. And her counterpart is kind of the other star of the book, a woman called Pat Gibbs, who I think is about 10 years older than Tommie and started working in the early 1960s and about at American Airlines. And she starts out life as like a 19-year-old from Springfield, Missouri, whose biggest dream in life is to become a stewardess supervisor. And then once she starts to encounter some of these incredibly sexist rules and appearance regulations and sees the way the company is treating the stewardesses, she flips completely the other way, she becomes a militant labor leader, a union organizer and kind of a professional pain in the ass. She is amazing, truly amazing. So, she taught me have a lot of the same goals. You know, they’re all about about advancing the rights of women in the workplace, and specifically flight attendants. They’re both feminists, they’re both, you know, labor is super important to them. But the book sort of culminates in a real face-off between the two of them, because Pat decides, along with some others to lead a campaign to leave the Transport Workers Union and to form an independent women led union, that is only American Airlines flight attendants. And this unit will negotiate with the airline directly, they will not have any intervening labor organizations, they will not pay dues to anyone, they’re just going to be out on their own. While Tommie takes the other tack, she says their safety in numbers. If we stay here, we’ll be running the damn union, and that she wants to stay with the Transport Workers, which is where the other airline workers are, you know, the cleaners and mechanics. They’re all with it and the pilots there with the Transport Workers Union. So there’s there’s a really big conflict that comes in the two of them are sort of facing off. And Pat wins, they have a vote. And the flight attendants at American Airlines decided to leave the Transport Workers Union and formed their own independent woman led union, which is a really, really groundbreaking moment in labor history, I think. And to get there, many, many other women decided to do this at the same time. I think the Transport Workers Union lost like 10 to 15% of their membership, because so many flight attendants left, it was like it was a huge blow. But I think they felt that they had no other choice.

Adam: So, final question. Before we let you go, I want to ask about some of the sort of bigger lessons in the present day. Obviously a lot of feminized labor, domestic workers and nurses, teachers, either are subject to dismissive anti-union rhetoric, even if they’re in a union, like a lot of teachers are nurses are, what are from your experience writing this book? Obviously, now we see an emergence of more unionizing. Not entirely “feminine,” quote unquote, but disproportionately such like things like Starbucks, which you’ll oftentimes hear push back saying, ‘Oh, well, these are just kind of, you know, sissy jobs basically.’ Right. Can you talk about lessons from your, from writing this book that you think that modern day labor activists or or union organizers can kind of take away from that? Because again, I think so much of what we depict as labor is, as we talked about in the show a lot, is this hard hat man, working in the sparks and steam factory, and how those how those prejudices kind of inform anti-labor attitudes.

Nima: Which was exactly like the airlines’ perspective, as you said.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I feel like the number one lesson is every worker is a worker, right? Like, there are no such things as like, some good workers, some real workers and some fake workers. That every worker is a worker.

Adam: Except for podcasters, they’re not real. Exception, I wasn’t gonna say that. But that’s a fake job. But go ahead.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: (Laughs.) There’s a real lesson to be learned, I think about fragmentation, right? So when you have this sort of like mass exodus of flight attendants from the Transport Workers Union, they do they get fragmented into these smaller unions, and there’s a strong argument to be made that then they had less power. But there’s also an argument to be made that when they were in the Transport Workers Union, they didn’t have that much power either. Like they were, their concerns were getting dismissed all the time. And that, you know, when it comes to forming and industrial union, fragmentation is everywhere, right? Like, that’s why it’s so hard to make one because like someone, there are some pilots here. And there are some flight attendants here. And they’re all working in like for their own needs. And, and, of course, that is to the advantage of the bosses. So even Pat now today says that she’s not sure that she made the right decision when she like, led this when she led the women out into their own independent union. And that she doesn’t know but maybe it would have been better to stay with the Transport Workers. So I think I think that’s hard to, I mean, it’s impossible to tell now, but I think the lesson we could apply now when we see so many people unionizing, but in like tiny unions and like independent, one store here, one store there, one warehouse here, is that like, it’s going to take a lot longer that way. And that I think that the lesson we could learn from what happened with the flight attendants is that like you can do the same thing everyone always says right, power in numbers.

Nima: Well, this has been so wonderful, Nell. We’ve been speaking with Nell McShane Wulfhart, whose book The Great Stewardess Rebellion: How Women Launched a Workplace Revolution at 30,000 Feet is out on paperback, in paperback, I should say in paperback now. Everyone should just read this book, which is absolutely wonderful and we cannot thank you enough now for joining us today on Citations Needed.

Nell McShane Wulfhart: It was my pleasure. This was really fun.

Nima: Awesome. And so that will do it for this citations needed. interview. Thank you, everyone, for listening. Of course you can follow the show on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed, and become a supporter of Citations Needed through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast. All your support through Patreon is incredibly appreciated as we are 100% listener funded, but that will do it for this episode. We will catch you very soon with more full length episodes and other goodies that we do from time to time. So thank you all for listening. Citations Needed’s senior producer is Florence Adams. Our producer is Julianne Tveten. Production assistant is Trendel Lightburn. Newsletter by Marco Cartolano. Transcriptions are by Morgan McAslan. The music is by Grandaddy. Thank you so much, everyone, for listening. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: And that will do it. We will catch you next time.

[Music]

This Citations Needed live interview was recorded on Thursday, April 6, 2023 and released on Wednesday, June 14, 2023.