Episode 98: The Refined Sociopathy of The Economist

Citations Needed | January 22, 2020 | Transcript

[Music]

Intro: This is Citations Needed with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson.

Nima Shirazi: Welcome to Citations Needed, a podcast on the media, power, PR and the history of bullshit. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam Johnson: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: You can follow the show on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed, become a supporter of our work through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson. We are 100 percent listener-funded. We have no ads, no billionaire backers keeping the show alive. It is all you, the listeners. So if you have not joined us through Patreon, we would absolutely appreciate that. It keeps the show going.

Adam: It’s true. Although technically one of our $5 patrons could be a billionaire. We wouldn’t know.

Nima: And if you are and you’re only giving $5, shame on you. (Laughs.)

Adam: Yeah. Fuck you, asshole. Give more money. Anyway. Yes, support us on Patreon if you can, everything there helps keep the show sustainable. And as always, please go to Apple Podcasts and rate and subscribe and leave a review if you can.

Nima: From its inception as an agriculture trade paper in the 1840s through the present day, The Economist has provided a gateway into the mind of the banking class. In a way, The Economist is an anomaly in the publishing industry. Not quite a magazine, not quite a newspaper; aspirational in its branding but bleakly limited in political ambitions; brazenly transparent in its capitalist ideology but inscrutable in its favorable spinning for American and British imperialism and racism.

Adam: Much of what we do on this show is to find hidden connections, ideology and subtext lurking behind the innocuous. But The Economist provides something different and to some extent challenging: a magazine owned by the wealthy, for the wealthy, that advertises itself as such. Its moral pretense: a long history of championing what it calls quote-unquote “liberalism,” a notoriously slippery term that, in The Economist’s world, views freedom to profit and exploit labor as interchangeable with the freedom of religion, press and speech.

Nima: As such, examining The Economist’s history, its connection to British and American banking interests and intelligence services, can tell us a great deal about the narrow focus of Western, and specifically British, notions of liberalism.

Adam: That is, the promotion of capital flows over justice, enlightened imperialism over self-determination, abhorring overt racism while promoting more subtle forms of race science and colonialism, all along easing the conscience of wealthy white readers that want to feign concern about human suffering but who have everything to gain by doing absolutely nothing about it.

Nima: Later on the episode, we will be joined by Alexander Zevin, assistant professor of history at City University of New York. He’s an editor at the New Left Review and author of the new book Liberalism at Large: The World According to The Economist, published recently by Verso Books.

[Begin Clip]

Alexander Zevin: One of the things that book tries to do is to bring the history of imperialism into the history of liberalism, and usually they’re not spoken about together. In fact, in many histories of liberalism you’ll get the impression that liberals were anti-imperialists, they were against the empire, but The Economist, and what I argue is the dominant strand of liberalism, isn’t. It’s consistently pro-imperial from the 1850s at the time of the Crimean War, and the Opium War in China, and the Indian mutiny, and many other conflicts all the way through to the present.

[End Clip]

Nima: Unlike a lot of the newspapers and magazines that we discuss on Citations Needed often, The Economist has an incredibly long history to examine. It was founded by Scottish hat manufacturer James Wilson in 1843 as The Economist: A Political, Commercial, Agricultural, & Free-Trade Journal. Wilson’s purpose? Quote: “to further the cause of free trade.” End quote. Pretty explicit in its ideology for even the first half of the 19th century. A hundred years later, by 1946, The Economist launched the Economist Intelligence Unit and has since acquired a bunch of consultancy and market-research firms.

Adam: Marx famously read The Economist during his efforts to develop his socialist theory and wrote many critical letters about it, especially during the American Civil War, which we’ll get into later. He said, quote, “the London Economist, the European organ of the aristocracy of finance, described most strikingly the attitude of this class.” So even since the 1850s and ‘60s The Economist was viewed as being the organ of aristocracy. Vladimir Lenin, who of course led the Russian Revolution in 1917, called The Economist quote, “a journal that speaks for the British millionaires.”

Nima: Yeah, it’s an amazing thing about looking at The Economist’s history because you can track what it is saying and who it is speaking for in real time against all of these other movements in history from pre-Civil War, through the rise of communism and socialism and then onto through the World Wars and colonialism and then post-colonialism. It’s an incredible view into the British colonial mindset.

Adam: Right. And so just a real quick breakdown of who actually owns The Economist, ‘cause we like to talk about ownership here, and the ownership of The Economist, like ownership of all media, is relevant to their ideological output. So The Economist is owned by the Economist Group, a British multinational media company. Its quote-unquote “brands” include marketing agencies, analytics firms, basically every genre of company whose self-descriptions are totally incomprehensible. In 1928, The Economist was sold by the Wilson Trust — James Wilson its original founder — to Financial Newspaper Proprietors Limited and quote, “an influential group of individual shareholders.” According to The Guardian, educational publishing company Pearson held a non-controlling stake from 1928 to 2015. Pearson sold its holding in the company for about $613 million. According to a 2012 Reuters article headlined “Private firms eyeing profits from U.S. public schools,” Pearson has made hundreds of millions of dollars off public schools, selling districts textbooks, standardized tests, etcetera.

Nima: Pearson is a British multinational conglomerate. It reportedly forecast profits of between $774 million to $840 million for the year 2019. The majority of Pearson’s stake went to the Italian holding company Exor which is owned by the Agnelli family. Their stake rose substantially from just under five percent to over 43 percent. The Agnelli family, which founded the car company Fiat, remains the largest shareholder. Why is this relevant? It is relevant because Exor has claimed to have a net asset value of almost $20 billion at the end of 2018 and assuredly more now. John Elkann, chief executive of Exor and grandson of Italian industrialist Gianni Agnelli, had been on The Economist’s board since 2009. Now, additional shareholders include what The Guardian has called quote, “a who’s who of British business dynasties, including the Cadbury, Layton, Rothschild and Schroder families.” End quote. Of course, Cadbury is the multimillion-dollar, multinational chocolate and confectionery company owned by U.S.-based multinational Mondelez International, a spinoff of Kraft Foods. Rothschild banking family is one of the world’s wealthiest families. In 2018, Bloomberg News called the Rothschilds’ wealth quote, “too diffuse to value,” end quote. The family has a 21% stake in the ownership of The Economist. The Schroder banking family, which owns a British multinational asset management company, has its wealth estimated by Forbes at $6.2 billion.

Adam: There are two articles worth reading that we won’t reference here, but we did read and did borrow some from that are worth checking out. James Fallows has probably the most famous criticism of The Economist, although it’s kind of devoid of politics and is mostly a sort of snide social critique of its kind of underwhelming writers. That’s called “The Economics of the Colonial Cringe,” and that was published in The Atlantic in 1991. Nathan Robinson, who we had on a few episodes ago, wrote an article in 2017 called, “How The Economist Thinks,” that is sort of a good rundown of their ideological output. So definitely check those out in addition to this episode.

Nima: The Economist is definitely what George Banks, the banker father in Mary Poppins would read—imperialist, colonialist—they lean on “tradition” and uh, you know, “discipline, rules, must be the tools, without them disorder, catastrophe, anarchy!” So they kind of have that tone and have had that tone for their entire history. And so what we’re going to do is, you know, we’re going to break down some of this, talk about their ‘hot takes’ on slavery, on imperialism, on coups, on cops, on, um, labor. Basically they always stand firmly on the side of power and definitely on the side of capital. As you can imagine, the voice of colonial banker and viceroy doesn’t really care much for labor rights or unions. The Economist has a long history of this stance as well.

Unsurprisingly, a piece from 1875 says that worker solidarity is doomed to fail because everyone has different interests and it recommends that workers just focus on being more responsible with the little money they do have. If they do this, they won’t have to rely on this union nonsense to push for, you know, higher wages. So they say this:

It is certainly astonishing that people are so slow to see. They can only stand out for better wages by means of thrift, that if they save, whether individually or collectively they do not need these elaborate associations…

Two years later, an article from May, 1877, is even more explicit in its contempt for workers, remarking that for the most part working men are “ordinary or inferior or positively idle or incompetent persons,” and simply seek to “pull down if possible these superior men to their own level,” by fighting for a minimum wage that The Economist just, you know, knows they don’t deserve. After all, they are inferior men. Minimum wages, The Economist argues, are at odds with the free-market system and merely a “pure question of supply and demand.” Adding that, “whatever efforts that unions may make to establish a minimum rate of wages to secure as they foolishly say and think ‘the avoidance of competition among workmen.’ All such efforts are futile when a scarcity of employment arises.” Anything they can do to depress the solidarity of labor, The Economist is going to go that way. Throughout the 20th century, the magazine continued on this theme. Union solidarity and strikes were an inconvenience to consumers and should be made illegal. In 1911, it pondered whether workers could be arrested for striking, suggesting, “Is it still feasible, by the strong arm of the law, to deter men from embarking on disastrous strikes?” that result in “public loss and damage accompanied by general tumult and disorder.”

By the late 1950s, The Economist floated the idea that strikes should be optional for union members, a sort of proto right-to-work stance, coupled with numerous articles lamenting how powerful and oppressive unions had become. Sure, they’re important for workers not to be exploited by capitalists, The Economist would say, but now they’re too powerful and they must be kept in their place. And after all, as noted in a March 1959 article, “middle-class” unions like teachers’ unions or steel workers shouldn’t really be asking for more than what The Economist says they deserve. That is, salaries that compete with those of doctors and lawyers.

The main thing about The Economist, Adam, that we’re going to get at through this episode, is the consistent posture that it strikes in its ideology and its tone. It’s basically the periodical equivalent of a manor house dinner party conversation between an aristocrat in a top hat and coattails and a monocle and, like, a bushy-whiskered big-game hunter in jodhpurs and a pith helmet discussing their thoughts about the world after dessert plates have been cleared by Black and Indian waitstaff and they’re lighting cigars. That’s what The Economist basically is.

Adam: So yeah, in previous episodes we’ve talked about the editorial tone of editorial boards as this view from above, and Jim Naureckas made a really interesting point in the Episode 16 we did about editorial boards that I’ve been thinking a lot about while working on this episode. He said that, one thing you notice that editorial boards do, which is so obvious in retrospect, but something I hadn’t really considered until I actually reheard that episode or when he initially said it, is that editorial boards never speak to people, they speak to politicians and elites and CEOs. So they’ll say, like, ‘It’s important that Jeff Bezos do this,’ ‘It’s important the president do this.’ Which if you think about it is quite strange. They’re not saying you ought to do this. There’s never a call to action. There’s never ‘Go protest this,’ ‘Go boycott this.’ Right? The New York Times and Washington Post speak to leaders-

Nima: Yeah, it speaks either up or laterally.

Adam: Yeah, you’re allowed to vote, right? That’s sort of your one input into the process, but you’re never allowed to protest, boycott, you’re never allowed to ever call a politician. There’s never a sort of specific call to action beyond passive voting. And the purpose of this, he’s told, is that ‘Politics is a spectator sport for you, while us serious people sort of sort things out.’ And the voice of The New York Times Editorial Board is this collection of 15 anonymous journalists who are there because they’ve made a career off turning in clean copy and not offending anyone. They’re going to tell you the way things are in this kind of detached voice without a byline. And The Economist is that but for a whole publication.

Nima: Right. For a whole publication for nearly 200 years. (Laughs.)

Adam: What’s striking about The Economist more than anything, and this is also true for The New York Times editorial board, which we also mentioned, is how little their tone has changed. It’s frozen in time to basically, like, the 1870s, like, you could, I could, aside from the kind of linguistic artifacts in terms of nouns and word usage, the tone itself is pretty much unchanged, which is quite remarkable when you consider how much other forms of writing have changed.

Nima: To put an even finer point on it, very occasionally there will be a bylined piece, but generally, the 99.9 bar percent of what it puts out is spoken with its own editorial voice and not specifically bylined. So on this episode we’re going to run down just a number of broad topics that The Economist has covered over the years that give quite an insightful, and I’ll say, stark, view of just that tone, just that voice, just that ideology that we have been discussing here. So what better to start with than something that shouldn’t be that hard to get right, which is The Economist’s take on slavery. Let us remind you all that The Economist started publishing in the 1840s. So with the prohibition of slavery within Great Britain in 1833, the British empire still of course continued to work with slave-holding societies to importing goods from slave economies, of course including the U.S. South. So, beginning their publishing before the Civil War, in the antebellum period, we can track what its viewpoint was in real time of the Abolition movement and then throughout the war.

Adam: Yeah. And so the reason why the context is important is because one thing we need to do while we go through these is, like, whether or not The Economist was, where they were on the kind of norms at the time. Not that that sort of justifies it, but slavery by that point in English proper society, even amongst the wealthy, was seen as very vulgar and sort of déclassé. It was, it was seen as corrupting white morals. And The Economist is always sort of going to be slightly just to this center-right of public opinion, but with a lot of just to the center-left optics and handwringing. And you’ll see this throughout this, they go sort of more hardcore to the right in certain things. But even that’s kind of a, a judgment call, I suppose. But what’s notable is that at the end of all their articles, the one impression you’re left with is that nothing’s really worth changing.

Nima: (Chuckles.) Right.

Adam: Um, it’s a roller coaster ride of handwringing. And ‘maybe this is important, it’s important to do this, and we need to have this right tone.’ But once you end up back at the end of the roller coaster, you are back to where you started.

Nima: So a perfect example of this, let’s take The Economist article entitled “The Slave Trade And Slavery,” from Saturday, June 28th, 1845. The article characterizes Africa and, yes, Africa as a continent, as quote, “uncivilized, unemployed, and unfed,” end quote, and positions the United States as the possible antidote to this. It frets that maybe slavery wasn’t the best approach, but still asserts that the United States and the slave trade was a necessary intervention for Africa’s benefit, Africa writ large. The article also argues that the forcible removal of African people was, quote, “a positive good,” but that slaveowners simply did it wrong, right? So we get to a process critique. According to the article, there’s nothing really wrong with American control over huge parts of Africa. In fact, it really, it says that that is necessary and essential, but maybe there should be more regulations, maybe, and enslavement itself wasn’t, like, the best policy, but hey, we are where we are.

This position by The Economist was reiterated year after year. Six years after that quote that we just read—this is from June 14th, 1851—an article came out called “United States — How To Get Rid Of Slavery” and in it, it basically takes at face value the notion that slave owners are there to protect and nurture those that they have enslaved, drawing parallels between — what else? — enslaved people and beasts of burden: animals, horses, oxen. The article paints a picture of some sort of quote “ethical capitalist,” the slaveowner who knows slavery is evil, but is basically just kind of waiting for the right time for emancipation and the European owner of capital who will eventually improve conditions for his own workers because of their importance to society.

Adam: Yeah. This was a pretty pro forma, sort of centrist, middle-way argument about slavery at the time, which is that we all want to end slavery. ‘We all know it’s evil, but we just can’t because if we do, the Africans are going to kill all the white people, and we can’t let that happen so there has to be a slow process.’ It’s kinda like Saudi reforms, right? There’s a 250-year reform plan and, like, we’re always just in your—but it’s like watching your child grow. You can’t really notice it because it’s just such a slow process. And this was pretty par for course at the time among people who were making a lot of money off slavery, but knew at that point, and this is important to understand that by this point, slavery was unique in the quote-unquote “Western World” to the United States. It was, it had been abolished all throughout Europe and the Confederate States of the United States were way out of whack with the general norms of Christendom.

Nima: And so what we see, yeah, is this idea that emancipation and abolition can come only when it’s most comfortable for who? White people. So the article says this:

The greater relative increase of the slaves than the free coloured population, and of the whites than the negroes, leads to the inference that to emancipate the slaves is to weaken and slowly to destroy the negro race in the States. When the fear of their predominance is removed, there will be less difficulty in recommending emancipation. It will come naturally to the slave-holders, just as a desire to improve the condition of the labourers in Europe has become prevalent in consequence of the evils which their deterioration inflicts on the whole society. Slavery is a great evil to the slave-owner, and he will willingly get rid of it when he sees no danger from emancipation.

Adam: Slaveowners are notorious for willingly getting rid of their slaves who are a source of great profit and allow them to do literally no work.

Nima: (Laughs.) So the article continues, quote:

The slower progress of the slave states, their inferior domestic regulations, the less security in them of life and property, the fearful passions encouraged both in masters and slaves, their loss of political power, and the danger which threatens the union — disturbing all the federal relations and alarming all reflecting men for the future fate of America — are all the consequences of the slavery which is preserved more from habit than a conviction of its advantages. The superior race continues itself in slavery by continuing the slavery of the coloured race. Every slave must have a slave-keeper. To emancipate the slaves is, in truth, for the owners to emancipate themselves.

Adam: This is totally off-topic, but if you ever want a good book on the internal handwringing of anti-slavery liberals, there’s a book called The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772–1832 by Alan Taylor. It won the Pulitzer prize, I think, in, like, 2013. It definitely does a lot of, like, reluctant-slaveholder kind of soft pedaling, but it’s a very, very, very good book with a lot of original research. Anyway, totally irrelevant. Just want to throw that in there. I really enjoyed that book. And so this was a very standard refrain that, and you have to keep mind to the point, this is key here, is that at the time, the British banking class was very, very aligned with the Confederacy. They had a lot of their debt and were invested in their economy to a great extent. This is reflected in The Economist’s editorial line. They wanted to keep the gravy train going or at the very least, if it did stop, they wanted it to stop over a course of, you know, a hundred miles and slow down. The abolition of slavery was a threat to their bottom line. But they also understood that they had to have this liberal pretense. So they’re constantly saying, ‘Theoretically, yes, slavery is evil, but, but, but, but…’

Nima: So, you’ll see in The Economist this consistent appeal to the softest kind of incremental emancipation. I mean, and they are not shy about this. The previous article is completely explicit, right? It says, it says, uh, “The fate of an inferior race when it comes freely in contact with a superior race.” You know, it’s like they’re really worried about what’s going to happen to freed slaves. They say this, quote, “To get rid of the negroes, though the process may be painful, the slaves should be gradually emancipated.” End quote. So that’s good. But then they say this, quote, “In fact their emancipation, and the slow, but not inhuman, extinction of the inferior race, seem identical.” End quote. So basically by freeing Black people, they will get rid of Black people, which means how do you make them survive? You keep them enslaved. So a couple years later, in 1853, they published an article called “Can Slavery Be Abolished?” As we know when you ask that question in a headline, what you’re actually saying, you know, and that clearly slavery cannot be abolished immediately. That’s simply just too rash a decision.

Adam: The article said:

But it can no more be put down than serfdom can be restored. Our reason and our hearts call on us to abhor it and to strive against it, and we hope to improve it. We ourselves will have none of it, as corrupting and degrading all alike; but it is a different question whether our abhorrence is a justification for making common cause with the enthusiasts of the Northern States in a crusade against slavery in the Southern States. The party in the North feels the pollution and the degradation which afflicts the whole society; but we have no more business, as a nation, to take up the cause of the abolitionists in the United States, and declare a war of opinion against the Southern planters, than we have to take up the cause of Mazzini and Kossuth, and assail the Governments and people of Austria and Russia.

And so you have this idea that it’s just not practical. It’s not going to happen.

Nima: And if we do it there, we got to do it everywhere. Right? Like, that’s the argument that you still hear.

Adam: I was told Russia invented whataboutery. But, man, that sounds, that sounds a lot like whataboutery to me.

Nima: (Laughs.) And so you see for years, even after the Civil War in the United States began, The Economist continues to do this in December of 1865, so this is eight months after the war has begun. The Economist published this, quote, “The economic value of justice to the dark races,” end quote, and insist that if slaves are eventually emancipated, there will still be a system of racial hierarchy in place and argues that nonwhite people would actually prefer that as long as white people control them in the right way. Which is amazing to hear that there’s again this sense of ‘Well, hey, you know, either way that this war goes, we’re still going to see the same kind of superior race ruling an inferior race.’

Adam: Right.

Nima: What is striking about this — we could go kind of week by week, we are not going to do that — we are going to jump now to January 18th, 2014, and The Economist publishes a review of a new book by Greg Grandin called The Empire of Necessity: Slavery, Freedom, and Deception in the New World under the headline, this, quote, “The Slave Trade: Not Black and White,” end quote.

Adam: See, guys, there’s a gray area here. There’s like, there’s the pro-slavery and anti-slavery, and we have to meet somewhere in the middle. Uh, and they said, the end line of the article is — I wish I could read it in a British accent, but I’ll just sound like a bad high school production of My Fair Lady so I’m not going to do that — “Unfortunately, the horrors in Mr Grandin’s history are unrelenting. His is a book without heroes. The brave battlers against the gruesome slave business hardly get a look in, although it was they who eventually prevailed.” So the general gist of the critique is that Greg Grandin gives short shrift to white anti-slavery forces and liberal forces. Now, you would think that maybe, I don’t know, there’s some sort of, like, institutional reason why they would want to make sure that people don’t think that, which is, there’s never, like, a mea culpa. There’s never sort of an examination in this review of, this was a posture taken by The Economist, which was, ‘Let’s outlaw slavery sometime around 1936.’ There’s this weird institutional defensiveness in this review. And then there’s a subsequent article in September of 2014.

Nima: Well, yeah, this is even better because there’s another review. They review another book that addresses slavery. Uh, Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and The Making of American Capitalism. And as you can imagine with that sub-headline for Baptist’s book, The Economist is not really thrilled about this book. And it reviews the book in an article they headline “Blood cotton.”

Adam: So the review begins by saying that they can see that the U.S. economy was driven by slavery, but are upset that they didn’t mention technological advances that increased the outputs of slavery as one of those things. So they sort of give short shrift to-

Nima: ‘You don’t give it its due, Baptist.’

Adam: Yeah. Uh, so they were really offended that they didn’t recognize the sort of liberal progress of the tools that slaves used. And then it ends with quote, this is the author, “Mr. Baptist has not written an objective history of slavery. Almost all the blacks in his book are victims, almost all the whites villains. This is not history; it is advocacy.”

Nima: (Laughs.)

Adam: Yeah. I don’t know what to say to that, man. I don’t have a glib remark for that except to say that it seems like the nuance police sure have a — and by the way, this of course is not a nuance they afford to left-wing governments they dislike, those are all just a bunch of genociding evil bastards — but slavery really needs a huge, a lot of gray area there. We’re not really sure if the whole owning people-

Nima: It needs more white heroes, Adam.

Adam: Yeah, they, they’re pretty upset that, like, the white people are villains and it’s, like, to paraphrase Ben Shapiro, ‘Facts don’t care about your feelings.’ That’s not something he seems to care about. So Edward Baptist, the writer, penned an op-ed in The Guardian calling them out, which you should read, it’s called “The Economist’s review of my book reveals how white people still refuse to believe black people about being black.” Which basically says that The Economist is a racist dinosaur. Again, their institutional soft pedaling of slavery for 30, 40 years and subsequent anti-Black colonialism in Africa. So the idea, they wrote a whole article critiquing the argument for reparations in just this last year, June of 2019, and they did the, they even did the, uh, Bradley Whitford from Get Out where they basically said that ‘We endorsed Obama.’ So it’s, like, that’s okay. And Obama opposes reparations and then they in the article saying we’ve elected an African American president, I think we’re always a work in progress in this country, but they’re sort of in progress. So now we’re going to move on to colonialism and imperialism.

Nima: Yes. What better than to transition from one kind of racism to the same kind of racism? So, obviously, having been publishing for as long as it has and being the aristocratic voice, the banking investment voice, the very high-society voice of the British empire, what better to advocate for than colonialism and imperialism? And it has done this from its inception. On September 23rd, 1843, issue number five of The Economist, there was an article, “The Prospects and Progress Of Australia.” And the article is basically just this brazen public-relations piece. It’s just like a press release for colonialism in Australia. It echoes tropes that Europeans were the first to quote-unquote “discover” the continent. And it really just does this, you know, fawning, this very obsequious gushing over British development in the region as you can imagine. So they say, quote, “…we may turn to Port Philip, a colony which has sprung up within these few years, unsustained except by the natural impulse of speculation and adventure. Four or five years ago, the very country was unknown.” End quote. And then it, you know, it talks about the British colonials who found it and named it. It was a quote “interesting region.” And so then you get this:

Scarcely, however, had the news been promulgated, when men, and flocks, and herds poured into it; that region which so recently echoed only to the footfall of the wandering savage, now boasts two thriving towns, with villages to match, a steamboat for its capacious bay, a judge, a court, lawyers, police magistrates, police constables, custom-house officers, three or four newspapers, a magazine, and an almanac; doctors, quacks, auctioneers, benevolent societies, mechanics’ institutes, botanists, prodigious flocks of sheep, wool merchants, candle manufacturers, and not a few tons of shipping.

Adam: When we did the episode, Episode 25 on the CIA-curated definitions of democracy, we talked a lot about how Max Roser, who’s an Oxford researcher, who’s quoted in all the Vox articles talking about how much democracy we have, in their definition of democracy, the Polity IV criteria, which is funded by the CIA, does these historical analyses of democracy, and the one democracy that exists in 1842 when they start the clock, and you see this in the Vox graph, is the United States. And so when you see these democracy maps where democracy starts spreading from the United States to, you know, sort of Europe and this and this, and then there’s these large blank swaths in Africa and Asia and Latin America, right? And you say, I emailed Max and I said, like, ‘Well, what exists in these blank slots?’ And he says, ‘Oh, well they weren’t sort of civilians or citizens, so we didn’t count them.’ And this really speaks to, I think what we’re talking about here, which is like this liberal, like liberalism for citizens without ever questioning who’s a citizen. And this was, this is a common critique of John Locke and other kind of quote-unquote British “liberals” who of course supported slavery, that it’s liberalism for those who sort of are worthy of it, and everyone else is either enslaved or a serf or poor, but they somehow don’t count against the nominal liberalism of a society because they’re not people. And even under the current definition that’s used in Vox today, if you’re a society that doesn’t have, that, you know, whatever, women can’t vote or this person can’t vote or, like, that’s the sort of not included. Palestinians can’t vote in Israel, but they’re not included. Israel is a nine out of 10 democracy because they’re not part of that citizenship.

Nima: Incarcerated people in this country, which has more people locked up, doesn’t count against the democratic nature of this society.

Adam: Correct. We are 10 out of 10 according to this criteria. And you, and so this ethos is not an ancient thing. In The Economist, Vox, sort of Max Roser crowd, the notions of liberalism are totally indifferent to who’s considered a human being. And I find that something fascinating, because in their minds, the extent to which colonialism is a moral stain, it is only a moral stain because it’s vulgar to whiteness and white morality because those are considered people and everyone else isn’t.

Nima: And so at every turn, The Economist keeps referencing back to its initial founding ethos. It’s not just about colonialism and whiteness and imperialism. What does it fundamentally also come down to? Free trade. So in the same article about Australia from 1843 it says this:

With free trade, our vast colonial empire may be made the natural draining field of our population for ages yet to come; without free trade, we but struggle in vain, and the grander the scheme for getting rid of an industrious but unemployed people, the more certainly may we calculate on ruinous reaction, involving hundreds, if not thousands, in destruction.

Nima: So again, colonialism is good for what it does for white people who don’t have jobs because they can then go and become colonialists themselves in the colonies.

Adam: Right.

Nima: And then of course as societies become less colonial, when there is more independence in the burgeoning postcolonial age of the mid-20th century, The Economist is struggling to figure out its place and its perspective. I say struggle reservedly, it’s not really struggling. But, uh, we will see, uh, for instance, and the article from December 13th, 1958, this view on, quote, “Africa and the West,” end quote, and the article unsurprisingly emphasizes the importance of Western influence across Africa, lamenting — what else? — the end of colonialism. And so you get this, quote:

African prosperity and progress depend almost wholly upon the outside and western world. Only in the Union have local resources and local production reached a pitch at which they offer some genuine independence of external influence. Virtually all the trade of Africa south of the Sahara is conducted with western Europe and north America.

Adam: So The Economist leaned heavily into the very far right-wing oppressive stance during the Mau Mau Rebellion. The history, by the way, we didn’t even really uncover much about it until about the last 10 years, which was from 1952 to 1960, the British brutally suppressed an uprising by native Kenyans against the British colonialists. Between 320,000 and 450,000 Kenyans were moved into concentration camps. Thousands of them died. More than a million were put in what was called quote-unquote “enclosed villages.” This was a brutal regime of killing, you know, thousands of people at a time and The Economist was very much for it. And you can see this in the kind of dehumanizing language they used. This is from an article from July 16th, 1955. The headline says, “Mopping-up Mau Mau” and it would go on to say, “The setting up of a semi-permanent man-killing department of the Kenyan government would be a bitter tailpiece to the emergency; it can only be hoped that the Mau Mau terrorists will not long stay on the run.” The whole article refers to them as terrorists. “The main object of the terrorists now must be to inculcate the myth of patriotic resistance.” It says that they were basically a bunch of ignorant natives who didn’t sort of know better. And of course they didn’t really report on the atrocities going on at the time. And at this point there was not really a distinction between British intelligence and The Economist. The Economist was basically an outpost of MI6, and their coverage of Mau Mau was basically just a reprint of the British Home Office telling them what to say. And so you sort of get these loaded terms, “terrorists,” dismissing their grievances and as always, there’s always a veneer of more liberal reforms that the Mau Mau need to consider to come to the political process and be civilized. This obviously goes along with their favoring of eugenics, population control, population handwringing, evolutionary biology. So in 1934, The Economist and, you know, eugenics was sort of mainstream in the 1910s, ‘20s, started falling out of favor after World War II. But, uh, in the early ‘30s with the rise of Nazi Germany, which of course was a regime based on eugenics, they discussed documents issued by the Departmental Committee on Sterilisation, recommending voluntary sterilization, quote-unquote “voluntary sterilisation” of people with disorders and disabilities. The Economist roundly approves of this decision by the Departmental Committee on Sterilisation in the United Kingdom, deeming this to be a more humane alternative to the compulsory sterilization, which they viewed as kind of déclassé and then they would say that there was no need for sterilization, which was only in Nazi Germany. They said, quote:

In Europe, so far, only Germany, Denmark and the Canton Vaud in Switzerland have sterilisation laws in force; but in Finland, Norway and Sweden laws are under consideration.

Nima: Please note that the Germany of note there is Nazi Germany.

Adam: Yeah, Nazi Germany. And so they, uh, they leaned into eugenics even after World War II. So they had an article called “Intelligence and the Birth-rate” in The Economist from January of 1947, they use the Eugenics Society as a credible source, taking its report at face value. It perpetuates the canard that quote, “intelligent parents tend to restrict the size of their families” and doesn’t explain how “intelligence” is determined, and leans heavily into IQ.

Nima: Yeah. It’s basically the pre-Idiocracy.

Adam: Yeah. And so they advocate that the state discourage “intelligent” families from limiting their size but actually incentivizes them to have more children so we can have presumably smarter families, which of course has the causality backwards. People have smaller families, not because they’re wealthy but because they’re rich and don’t need them. The article conflates income level with intelligence level and uses a very common term up until the ‘70s called “problem families,” which were seen as being families that were a drain on society by using too much welfare. And then in 1950 they also again, in December 1950, in an article called “Defining Problem Families,” The Economist also endorses the Eugenic Society of the United Kingdom and uses the term “problem families” to mean large families or working-class families. And they say quote:

The main purpose of an investigation sponsored by the Eugenics Society into problem families in Bristol was to explore a method of enquiry which could be applied to the country as a whole, and thereby indicate how many families live in such subnormal conditions as to be classified as ‘problem.’

And so basically again, something like eugenics and inferior families and problem families and they’re poor is not because of capitalism, right? It’s not because of some system. It’s because they’re either genetically inferior, where they have a moral failing and the notion of children being happy or loved in a problem family just doesn’t exist. They say these problems families have a quote-unquote “animal existence.”

Nima: It’s pretty clear the perspective that they are pushing here. In March 1958 The Economist published an article about, “The Hundred Million. Question,” and it is about how population growth remains, quote, “the root of almost all,” end quote, of Japan’s problems. So you can imagine where this goes. Japan, The Economist writes is quote “uninhibited by western breeding habits,” end quote, and therefore, the society demonstrates the, quote, “classic Asian pattern” end quote, of a birth rate that exceeds their young death rate. And so this then creates population growth problems, per The Economist, which writes this, quote, “Japan’s death rate and birth rate are both low enough to place it in this respect among the world’s advanced countries.” End quote. So they’re not living up to the advancement that they should have because they are not being Western enough in their breeding.

Adam: Yeah. Well, it’s eugenics. So they’re kind of soft eugenics, where also, they also engaged in this in the 1990s which was common in places like Charles Murray in The New Republic, Andrew Sullivan, et cetera. They also were huge promoters of The Bell Curve by Charles Murray. And they say that, quote, “inequality might be inevitable” and that while this might be a hard pill to swallow, it has to be swallowed nonetheless. And they imply that intelligence and income levels are inextricably linked in their review of his book and they tell anti-racist, anti-capitalist IQ opponents to calm down, writing, quote, “What the IQ debate needs more now is a dash of cold water. Opponents of testing should forget their overheated rhetoric about legitimizing capitalism and racism.” Um, and they support IQ tests. They suggest that IQ tests aren’t the problem, but only Charles Murray is the problem because of his kind of right-wing white-nationalist baggage. So again, you have this gesturing towards liberalism, but then ultimately sort of buying in the fundamental basics of what’s being argued.

And the reason why race science keeps popping up on the radar, aside from never really going away, the fundamental contradiction of neoliberal capitalism is that if you believe people don’t succeed and a certain race of people as it were, continue to not succeed, and you can’t blame the system as being fundamentally racist at its core and conservative at its core, and yet people of certain races remain poor and remain incarcerated, the only logical conclusion you can reach from that — because you can’t say it’s the system, right? Because the system’s good — the only logical conclusion you can reach from that is eugenics. It’s that they’re genetically inferior. That is why they keep turning up in prison and why they keep being poor. Because the only alternative to that is that the system itself is fundamentally flawed, and you cannot acknowledge that, especially when you’ve built your entire brand on it for 150 years. So they frequently soft pedal and dabble in race science and kind of poo-poo the, uh, the college-campus left as being overly precious about the sort of hard reality of evolutionary Darwinism.

Nima: The Economist is always in favor of making the world safe for democracy, mostly in the form of capital investment, but only of course when it fits their own interests. So take, for example, to start this from September 12th, 1970 in an article about the recent election in Chile that brought President Salvador Allende, the first socialist president to be elected in South America, to power. And so The Economist reacted this way. They wrote, “The marxist-leninists have staged a revolution by ballot box in the one country in Latin America where the armed forces are unlikely to intervene in the name of democracy.” That was published pretty much exactly three years before the U.S.-backed coup that overthrew Allende on September 11th, 1973. Just days after that coup, The Economist was exalted in an article headlined The End of Allende, saying this, “The temporary death of democracy in Chile will be regrettable, but the blame lies clearly with Dr. Allende and those of his followers who persistently overrode the constitution.” So clearly the military coup is not the problem. It’s the unconstitutional leadership of the elected president. The article goes on, stating with an impressive level of indignation this, quote, “General Pinochet and his fellow officers are no one’s pawns. Their coup was homegrown and attempts to make out that the Americans were involved are absurd.” End quote. Now echoes of The Economist’s take on Allende could be seen late last year in November 2019 when another elected socialist leader was overthrown in a coup, this time, Bolivian President Evo Morales. In its article reacting to those events, those recent events in the article The Economist published called Was There a Coup In Bolivia? that had the subheadline, quote, “The armed forces spoke up for democracy and the constitution against an attempt at dictatorship.”

So The Economist is clear where it stands about this act, and it should be no surprise, they don’t believe this was a coup. And why not? Well, because they say there are basically no coups anymore. Quote:

Since the democratisation of the region in the 1980s, coups have been rare. But the very idea has become a potent propaganda tool, especially for leftists. Scarcely a week goes by without Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s fraudulently elected dictator, claiming that he is threatened by one. Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua says the same. Dilma Rousseff, a leftist president in Brazil who spent her way to a second term in violation of the country’s fiscal responsibility law, also claims that her impeachment in 2016 was ‘a coup’ even though it followed strict constitutional procedures.

Nima: End quote. The article also offers a mere policy critique of what was clearly a coup in Bolivia, including some classic handwringing about the militarism of the coup, they don’t say coup, but of the coup. This also reinforces the narrative that, uh, it wasn’t a coup, right? What The Economist is trying to push, this could and should have been done peacefully. The intentions were ‘pure.’ The article says this, quote:

That the army had to play a role is indeed troubling. But the issue at stake in Bolivia was what should happen, in extremis, when an elected president deploys the power of the state against the constitution.

Nima: To discuss that and so much more, we’re now going to be joined by Alexander Zevin, assistant professor of history at City University of New York, CUNY, and an Editor at New Left Review. He’s the author of the new book Liberalism at Large: The World According to The Economist, which was recently published by Verso Books. He’ll join us in just a moment. Stay with us.

[Music]

Nima: We are joined now by Alexander Zevin. Alexander, thank you so much for joining us today on Citations Needed.

Alexander Zevin: Thanks for having me.

Adam: I want to start off by doing what you did in high school debate, which is sort of set the terms of what we’re talking about, because so much of this relies on that. You detail in your book quite a bit, and this is in fact your entry point and in the title of how you talk about The Economist, about this label of liberal or liberalism. One thing The Economist does really well is this very slippery definition of liberalism where we conflate, like, civil rights with IMF restructuring programs. It’s sort of, they’re all part of liberalism in their world. And you go into detail about that specifically even how different countries, you know, from Spain to France to the UK to the U.S. have different definitions of liberalism. So before we start off, I wonder, I wanted to ask you is, what is your definition of liberalism? And how do you think The Economist editors, if they were standing here, how do you think they would define the term?

Alexander Zevin: I’ll do my definition first and then we’ll see about what The Economist editors would say. The way that liberalism is usually defined and the thing that I’m pushing against is as a kind of grab-bag concept, everything that’s good about the West or anything that the person in question wants to associate with a kind of middle-progressive path through history gets added to liberalism. And so it’s very difficult to actually understand or decide what that means. One of the ways I try to get around that is by offering an historical definition of liberalism. So, instead of starting in the 17th century with someone like John Locke and you know, his concept of life, liberty, and property, the recent history textbook on political theory by Alan Ryan begins right there. That’s liberalism: life, liberty and property, with a few things added on. Or with Adam Smith, author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations in the late 18th century, who talked about liberal systems and liberal policies, but didn’t mean what we mean by that. I start in the early 19th century, basically at the moment when capitalism, the French Revolution, had begun to revolutionize and change our, our understanding of what politics and economics are, and when for the first time people called themselves “liberals.” And I think that’s important, the moment at which people begin to actually identify as liberals and to group themselves together as liberals. That’s the moment when the history of liberalism begins. And from there I try to establish an actual sort of record of what liberals have said and done. And then speaking to the actual definition, what did early liberals call themselves? Or what did they mean by liberal? So on the continent of Europe in the 1810s and ‘20s, liberals that, you know, in Spain in 1810 to 1812 the Napoleonic armies swept the Ancien Regime away and they’re looking to expel them, get rid of Napoleon’s armies and a group of people in the Cortes in Cádiz begin to call themselves Liberales. What do they mean by that? They mean something like, in contrast to the Ancien Regime, constitutional monarchy, responsible government, a kind of minimum of civil liberties, of freedom of association, freedom of the press, and careers open to talent. And in the case of Spain, they also mean universal male suffrage. Although that’s not the case for all liberals in France. That won’t be the case. And there are specific historical reasons for that. So the definition is political in Spain as well as in France, the definition of liberalism is political. It has to do with sort of responsible representative forms of government, but it isn’t necessarily economic. And that’s what makes liberalism in the UK unique. The word “liberal” travels from Spain in the 1810s to France after 1815 and the Bourbon Restoration, when Napoleon was defeated, the Bourbons are put back on the throne from 1815 to 1830, people begin to call themselves liberals. And there they mean something like a middle path between both the ultra-royalism of the Ancien Regime and the calamitous popular radicalization that was Jacobinism and the terror after 1789. So it’s a kind of middle path, again, primarily political in orientation, looking for a constitutional monarchy limited in scope with some forms of civil liberties and some accountability to a highly restricted electorate. Political liberalism triumphs on the continent of Europe, right? But one of the things that makes The Economist so important is that alone in Britain uniquely, we get a combination of political liberalism of the kind I just described to do with civil liberties and representative government with economic liberalism, which foregrounds theories of the free market, free trade, an absolute right to private property, low taxation. And this sort of synthesis of economic and political liberalism gives rise to what we would call classical liberalism. And in the 1830s and ‘40s, The Economist kind of emerges as the greatest champion of that kind of liberalism.

Nima: Which inherently goes hand in hand with racism and imperialism and colonialism. Right? It’s kind of inseparable from those.

Alexander Zevin: Right, and then the story moves on from the 1840s to narrate the fact that once that classical liberalism has emerged, what do classical liberals do about the three things that classical liberalism doesn’t have an answer for, right? Which is the rise of demands for mass democracy from working class people, which don’t figure in the core doctrine, there’s no sense that there needs to be democracy, just some form of responsible government. Somebody has to be accountable, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be to the people — far from it. Then the spread of empire. Right? What do liberals say about the fact that, you know, not just Britain, but all of these other European, and then of course America, is going to get in on the imperial act, do liberal civil rights apply to the colonized or not? Right? They have to have an answer to that, and often they have very bad answers, which gets to your racism point. And then, thirdly, what about the rise of high finance within the global economy? Right? Classical liberals are not thinking about banking, money, speculation. They’re talking about agriculture, trade and industry. So what the hell do liberals have to say about the fact that, you know, people are sending their capital this way and that to invest all over the place? Is that productive of value, or is it just kind of speculation and greed? Right? So those are the, yeah, the story kind of picks up from there and then becomes more kind of contemporary because we’re still dealing with those problems.

Nima: That seems to be a very consistent piece of what you see in the reporting and the commentary in The Economist over the years. There are some real touchstones. Some are uber-obvious, like imperialism and colonialism, pro-war when it suits the interest of capitalism, maybe less so when it does not. But earlier in the show, we went through some of the history of the publication, talked about its founder, Scottish hat manufacturer, James Wilson. Can you sort of unpack for us what this structure is, what the culture is there, and maybe how that’s different from other magazines or newspapers like it?

Alexander Zevin: Right. Well, The Economist starts out, it’s on a shoestring. It’s really James Wilson’s publication and there are a few other people that work there. At first, Herbert Spencer, the guy who comes up with the notion of social Darwinism, the idea that we should apply evolutionary concepts laid out by Darwin to classes within the nation, works there. So do a few other important figures that I could discuss. But it’s a small operation and it’s a vehicle for James Wilson to basically parlay his expertise as a theoretical economist talking about free trade, making arguments for free trade, to catapult him into parliament. And in 1847, a year after the Corn Laws are abolished, he begins his ascent, which is really remarkable and rapid, through the hierarchy of the British state into the treasury. And eventually he becomes the first chancellor of the Exchequer of India. And if he hadn’t died in India, he might’ve become the chancellor of the Exchequer back in Britain.

Nima: Right. So it was like his campaign book, you know, like, politicians publish a book with their theories on basically their platform in order to move their career along. But then it turned into this other thing.

Alexander Zevin: Exactly. Once he enters into government, The Economist serves to amplify his political career and his message.And that’s one of the fascinating things about the early Economist. We can read it to better understand government policy in Ireland during the famine in the late 1840s because Wilson is seeing these reports that are coming in from Ireland about the Irish poor laws, and he’s making recommendations to the cabinet and he’s writing minutes for the treasury. So the direct kind of link between the laissez faire attitudes of the British state towards that famine, which resulted in over a million Irish dead and a million more that emigrated, fled. You can see it clearly. Now the culture changes, though. Wilson is, he’s a rich kid, basically. I mean, he, he inherits a lot of money from his father, gives him a lot of money to buy his hat factory and to start out in business. And so he’s not exactly coming from the bottom up, but nor is he an aristocrat and nor is he particularly well-educated in the way that future Economist editors will be. The Economist kind of grows and expands. It becomes more and more linked to the sort of highest echelons of British society. And by the 20th century, it’s changed quite a bit. And then it begins to look a lot like what we think of now as this extension, sociologically, of Oxford and Cambridge, the kind of creme de la creme of British society. And you know, many people will discuss The Economist as a common room, uh, with people having arguments about the big issues of the day. And some people find this a very irritating aspect of The Economist.

Nima: (Chuckles.) Yeah, I mean, I’m sure. And as the former Economist editor Gideon Rachman told you, which is in your book, he said, quote, “The lack of diversity is a benefit.” End quote. And so, I mean, this is embraced. This is really the culture of super elite intellectual aristocracy, is really embraced by this publication still.

Alexander Zevin: Yeah. Well what he meant by that, to be fair to Gideon, what he meant when he said that was that he was speaking about the kind of sociology of the place. When you think about, and this is something I failed to mention, it’s the most obvious thing, is that what do we know about The Economist? It’s that there are no bylines, right? There are no bylines at The Economist, which was fairly common in 19th-century British journalism, but just isn’t today almost anywhere else and I think what he was trying to explain to me, and I would agree with him, is that for that cohesive voice that pronounces from on high, ‘Give Zimbabwe three things that it must do tomorrow if it’s going to save the currency,’ you know, which would usually involve privatizing the sewage system and abolishing public schools. I can’t think of a third thing. But in order for that to actually work, there does have to be some kind of basic, shared, taken-for-granted assumptions.

Adam: Well, right, ‘cause in a contemporary context, I mean, anonymous writing is supposed to protect people who are scared of power. The Economist does the inverse. It uses it to protect and to promote the interest of capital. So it has this very warping effect. I think the one argument that I’ve seen, and I think it’s an argument I’ve made, is that the extent to which everyone else started shifting to more traditional bylines, I think, one of the main reasons The Economist doesn’t, and I think the reason why editorial pages don’t, is because so much of their stuff they publish is just power-serving schlock that nobody really wants to put their name on it.

Alexander Zevin: At The Economist.

Adam: Well, anywhere. I meant like specifically the existence of editorials. We did a whole episode on the artifact of editorial pages. And you know, writing a sort of, ‘cause, again, there’s this on-high scoldiness to it that, um, you read these things and halfway through you’re like, ‘Who the fuck are you?’ Like who are you to tell Bolivia what they need to do? Or who are you to tell Zimbabwe what they need to do? You’re just some guy. You’re just eight people who went to a good college. Like, you’re not. So the anonymity allows you to sort of launder your conflicts, to launder your, obviously your sort of racial and gender dynamics. It’s, I don’t know, I think it’s the editorial tone is this weird 19th-century artifact that still exists, and I find it amusing more than anything.

Alexander Zevin: Yeah. I just would add to that that I agree, and the thing that’s interesting to me is that the tone develops out of this really unique worldview, this unique politics that’s based on something new in the world when it first appears, which is the spread of British capital abroad. And so this voice that can be so jarring when we hear some anonymous voice at The Economist telling Bolivia what it should do or that there was no coup there, for example, most recently.

Adam: Right. It was right after they scolded Maduro for being a conspiracy theorist for claiming there were coups when they, when there was literally an open coup ongoing right now.

Alexander Zevin: Well, of course, anything Maduro says is wrong, I guess.

Adam: Wild conspiracy theory, even though it’s on the U.S. State Department’s website, you can go look at it.

Alexander Zevin: Well, for a long time, even using the word “imperialism” was a mark of kind of insanity and inanity.

Adam: And the extent to which it did exist, it always existed 30 years ago. Right? It sort of disappeared 30 years ago. Somehow the British elite and capital became super woke magically, and imperialism no longer exists or, God forbid, morphed into something more sophisticated.

Alexander Zevin: Exactly. Yeah. No, I was going to say about the tone of voice is that it emerges as the voice of capital. Basically The Economist is the first magazine anywhere in the world to tell British investors or investors where to place their money and what risks they run in placing their money abroad. And so it’s this ingrained, calcified way of speaking about things that’s based on the fact that in the 19th century, people read The Economist to understand if investing in the Argentine waterworks or buying Indian government bonds was a good bet. And I think that’s where it rises. Yeah.

Adam: Yeah. And this brings me to one of the main problems with doing an episode on The Economist, which is so much of what we do on the show is showing unseen or hidden forces, right? The libertarian astroturf of Mike Rowe or something. But The Economist is very overt about its capitalist imperialism. Like, it’s not, there’s not a ton there that’s really a mystery.

Nima: They actually publish all of it.

Adam: And they lean into it, they’re like, ‘Oh, we’re, you know, we’re the magazine of Air Force One and we’re the magazine of the elite, like, go fuck yourself.’ And of course it’s very aspirational as well, right? It’s a marketing thing. And one of the things I do want to talk about is their interesting relationship with imperialism. Which is to say it’s pretty much 90 percent for it and indeed we can go into detail about how they’ve worked with it. I think that their relationship with apartheid South Africa is actually an interesting gateway. We spent a lot of time reading their history of through the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s about the relationship with South Africa and apartheid, which is sort of an interesting kind of moral litmus test and you tell me what you found in your research, but it’s, like, they do a lot of scolding, like, they’re definitely critical of apartheid, but then it’s like, ‘Oh, well, Nelson Mandela deserves to go to prison because he’s guilty.’

Nima: Right.

Adam: So it’s sort of, when, you know, earlier when I asked you to define liberalism, I feel like that’s actually a pretty good definition of British liberalism. It’s sort of like ‘There’s this problem, but you can never do anything about it.’

Alexander Zevin: Hmm. I like that.

Adam: I want to ask you about their history with British imperialism sort of generally. We can get into the specifics later. They, they were very hardcore militantly opposed. They obviously promoted imperialism in India. They promoted imperialism of Africa specifically. They called for what you said was the “pitiless repression of the Mau Mau terrorist” — those were their words, not yours. And then of course, they supported the invasion of Iraq, invasion of Libya. I mean, you sort of name it, they supported the war. What does their support for imperialism say about their notion of liberalism and how they view freedom and even notions of liberation or liberty?

Alexander Zevin: Right. So one of the things that the book tries to do is to bring the history of imperialism into the history of liberalism. And usually they’re not spoken about together. In fact, in many histories of liberalism, you’ll get the impression that liberals were anti-imperialists, they were against the empire. But The Economist, and what I argue is the dominant strand of liberalism, isn’t. It’s consistently pro-Imperial from the 1850s at the time of the Crimean War and the Opium War in China and the Indian mutiny and many other conflicts all the way through to the present. It’s extremely consistent. And I think in the 19th century, that has to do with the fact that when the liberals who start The Economist, when they begin, they accept the theory by which free trade equals peace and goodwill among men, right? This is the Cobdenite vision of liberalism. But within a few years, James Wilson and Richard Cobden have a terrible falling out, and it’s over this issue of empire. James Wilson, right? We know he entered government and there prosecuted numerous wars. He realizes that in order for free trade to triumph, we’re going to have to actually fight. In other words, free trade doesn’t equal peace. In other words, free trade is going to require us to attack China.

Nima: Yeah, demands war.

Alexander Zevin: Right. And we’re going, you know, the unequal treaties with China, which to this day, fuel Chinese sentiments of nationalism, were imposed in the 19th century to open it up to Indian opium and the narco-capitalism that the British were peddling there. And so I think to zoom out on your question, I can talk about individual cases that interest you, but to zoom out on your question, basically the spread of capital globalization in its 19th-century and 20th-century forms have required imperial rule domination, dominion, management, administration, and The Economist has provided a very clear illustration of that.

Nima: Well, yeah, I mean, I think that’s what’s amazing about having The Economist as a document. I mean we mentioned earlier on the show that their archives are not just readily accessible, you need to actually pay to really gain access to all of their archives in a way that is very different than even, you know, The New York Times, like, and that once you start digging in there you realize why — maybe — because even though they’re still peddling the same stuff now in a way that they were then, it just sounds a whole lot worse then, because for instance, The Economist’s relationship with slavery for a publication this old, you can actually look at what was written contemporaneously with the American Civil War.

Adam: Both sides. Both sides, Nima.

Nima: (Laughs.) And so, you know, can you maybe talk about that, The Economist’s relationship with now what I think in retrospect we can see as probably a pretty bad take on that, but at the time it really just sounded exactly the same as then its later defense of not supporting boycotts over apartheid. You know, that it’s, it would punish the slaves as well as the British consumers and the economy, you know, it’s the same thing as like, ‘Oh, well, Black South Africans will be unemployed if there’s a boycott, so therefore’—it all winds up being the same thing. You can kind of document this for nearly two centuries.

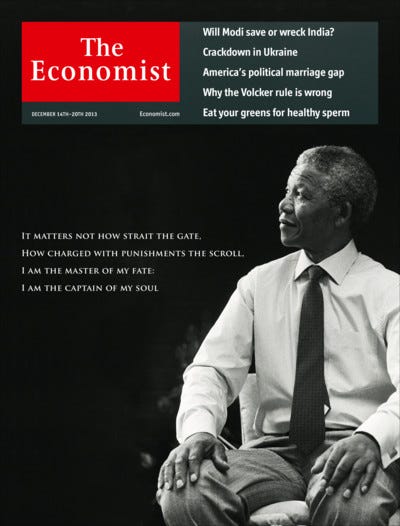

Alexander Zevin: Yeah, I like the line through that you’re drawing between the Civil War and South Africa. There is a lot of consistency there and it is just as disturbing in the 19th century as it is in the 20th, although of course, you know, by the time Mandela dies, The Economist runs a cover with him on the front. You know, that implies that all along they had stood with him for freedom.

Nima: Of course. Of course.

Alexander Zevin: I mean, I think that editors at The Economist are themselves not always aware of the kind of record and the Mandela cover would suggest that. In the 19th century though, again, in terms of what the book reveals, I’ve read many books that suggest that The Economist and liberals in general in Britain were opposed to slavery and took the side of the North in the Civil War. They were fans of Lincoln and so forth. The Economist shows a liberal periodical led by Walter Bagehot, who, first of all, he’s totally unimpressed by Lincoln. He thinks the American Constitution is a shambles. He’s not totally wrong about that, by the way. He has a pretty good read on some of the problems inherent in the American Constitution, which he says, you know, nobody can even, they’ve given themselves a Constitution that nobody can ever change — which seems to be the case — but in terms of slavery, he actively roots for the South to hold out. He thinks that a unified America will be a threat to the British empire. They’re going to be able to levy tariffs on raw cotton. Right? The South is offering to basically ship cotton to British mills in Lancashire at a very low tariff for no tariff at all. He views it through the prism of kind of what’s good for business and also what’s good for British imperialism. And, you know, he doesn’t take what one of his friends calls a high-minded view on the issue of slavery. So here we see where pragmatism leads you. You know, the so-called center, moderation, pragmatism can lead you down some pretty dark paths, and Marx is reading The Economist. He’s a consistent reader of The Economist. One of the fun things about doing this book was, as I read The Economist and was shocked like you at some of these positions that they take, reading Marx, who in notes to Capital or in his own journalistic writings about the American Civil War, about Lincoln or about the Civil War in France, constantly refers to The Economist and he really goes to town on Bagehot and the editorials about slavery, he says, you know, finally when Bagehot says, you know, it’s an issue of tariffs and he wants the South to hold out, Marx says something like ‘At last, the cloven hoof peeps out.’

Adam: Oh, nice. That’s a good take.

Nima: (Chuckles.)

Adam: They had such better insults back then. So I think today, people are super precious about journalists working with intelligence agencies, but it was, it was pretty common during the Cold War. There, you know, there are reasons people will give that it was sort of, there’s an existential battle against communism, et cetera, et cetera. Now it’s sort of seen as being tinfoil-hat stuff, but it was quite common back then. And The Economist again leaned into this as well. You touch on their relationship with MI6, CIA, especially in Latin America where they view themselves as being part of an intellectual bulwark against communism.

Alexander Zevin: Yeah.

Adam: Can we talk about the relationships with intelligence agencies and to what extent it was sinister? To what extent it was just ideological alignment, and the extent to which we actually don’t really know?

Alexander Zevin: I guess the answer is all three. But I did find individual cases of both ideological alignment and of the sinister. So, you know, again, part of the story here is the way that liberalism, far from being kind of anti-statist, requires the state to do things for, to create the conditions in which people will behave as good liberal subjects. They will accept the market, they will work for a wage, they will not rely on welfare and so forth. So the same holds true when we’re talking about foreign policy and since The Economist is drawing its staff from the elite universities and has been since the 1840s connected to the British state, the treasury, the City of London, it’s only to be expected that through it would be channeled spooks. And so one of my interests was to find out the way in which this worked. In some cases, we have kind of these, um, real characters — to put it, I guess, quite mildly — who are actively planting misinformation or disinformation in the economy. This is what fake news used to be called. I know that for certain sections of the Democratic Party, fake news only came about with the election of Trump, but actually it proceeded it and it was, um, it was, it was-

Nima: (Chuckles.) What!?

Alexander Zevin: I know, I know. Don’t tell Rachel Maddow.

Adam: Are you suggesting that Western intelligence agencies can engage in disinformation? I’m only told that it’s teenagers in Moscow. Sorry, go ahead.

Alexander Zevin: No, no. Yeah, it was a shock to me too. So I can talk a little bit about the individual cases. One of the institutional connections that is really clear-cut though, and thus structural, is that the Labour government — though this should tell us a little bit about what Labour Party in Britain was like in the post-war period — set up a thing called the Information Research Department out of the Foreign Office in 1948. And this was basically designed to write negative stories about Soviet communism and the potential spread of Soviet communism throughout the world. This is pretty early on in the Cold War and many Economist journalists, not just the ones who were kind of explicitly working for or with intelligence agencies, accept packets that are sent to them by the Information Research Department of articles that they might be interested in or bits and bobs of text or so-called secret files that they might be able to put in a story, or a lead, or you know. So this kind of management of the press might not have appeared to them to be at the time anything untoward, but it certainly should give us pause when we contemplate the so-called freedom of the press.

Nima: In the post-Cold War era, you know, The Economist has remained relatively consistent. I mean, it was publishing Jeffrey Sachs calling for shock therapy in post-Soviet economies, precipitating an enormous collapse that hurt a lot of people. But when we talk about today, how do you, after all your research, after writing this great book, like, how do you see their take on Trump insofar as if you actually dissect a lot of what Trump is trying to do and has done, it intersects very, very closely with what The Economist has been calling for for well over a century and yet there’s a uncouthness. Is it simply personality that they are disagreeing with, or how do you read their kind of dissatisfaction with the current state of things?

Alexander Zevin: Yeah, so obviously for them, the election of Trump, the victory of Brexit, and there are other examples in the last few years, have been shocking. They failed to see those coming, and they’ve worked assiduously against them. I think that in many ways the hype around Trump is, well it’s over-hyped because, you know, what he has managed to achieve and the degree to which he has diverged from America’s foreign policy consensus I think is pretty minimal outside the realm of discourse. There is the issue of free trade and for them that is fundamental to the liberal DNA. And there it looks as though he is willing to try to renegotiate these trade deals to get a better deal for, well, I guess U.S. multinational corporations, or whoever is going to benefit from those trade deals. It’s not clear that it’s the American worker, but I guess I agree with you that basically the style that Trump represents, the fact that he takes the mask off of American bullying, and unlike Obama or Clinton, is not sort of sugarcoating the American imperialism abroad is deeply disturbing. And you know, of course it’s truly upsetting for them to hear someone, let alone the American president insult the glorious North Atlantic Treaty Organization. This, uh, you know, alliance, the idea that the, we can’t question the purpose of NATO over what more than two decades after the end of the Cold War, about three decades when, uh, when it’s fighting a war in Afghanistan that, what, is 17, 18 years old now, it seems reasonable to me, but-

Adam: To me, Bolsonaro, you know, they have that infamous tweet that said quote “Bolsonaro is a dangerous populist with some good ideas.” Pretty much thumbs up The Economist right? And you actually see this with how they respond because we also spent a lot of time looking at old articles about how they responded to Nazi Germany and it’s so-

Nima: It’s not dissimilar.

Adam: Yeah, they’re just handwringing. A lot of it’s tonal. It’s, you know, ‘The rhetoric’s bad. They’re a bunch of nasty racists, but, like, they’re developing or they’re progressing in this front.’ And you’re, like, I mean, again, I get their whole shtick is to sort of look at both sides and kind of like provide a sober analysis, but then they smuggle in moral content. Like, it’s not just calling balls and strikes right? At the end, they’ll sort of be, like, they’ll give a policy proposal, which of course has moral content. You know, we need to wait and see or do this.

Nima: Right, like support Mussolini.

Alexander Zevin: Right. Oh, well, yeah. I mean there, I mean there’s all kinds of, yeah. I mean The Economist is thrilled by Mussolini. Why? Not because he’s not a Democrat, but because he is going to tame inflation in the battle of the Lira in 1920s Italy, you know, he’s basically going to impose an austerity package on the Italians to bring down the inflation and make Italian debt sustainable.

Adam: And also fight communism.

Alexander Zevin: Right, right. And so we’ve talked about empire, right? We’ve talked about the fact that liberals, well, in my view, don’t really acknowledge the fact that they are deeply complicit, at least this dominant form of liberalism with imperialism, but what about democracy? You know, for me it’s quite consistent. They have supported Bolsonaro to an extent. They’ve supported Macron in France. You mentioned these other historical examples. Well look, liberals traditionally haven’t been in favor of democracy. So when a strong man comes along, who offers to impose market rigor on an economy that, you know, or a society where workers are running rampant, demanding, you know, proper wage or conditions of work or let alone something as wild as the ownership of the means of production or, in our own day, healthcare.

Nima: Or a vote.