Episode 87: Nate Silver and the Crisis of Pundit Brain

Citations Needed | September 18, 2019 | Transcript

[Music]

Intro: This is Citations Needed with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson.

Nima Shirazi: Welcome to Citations Needed a podcast on the media, power, PR and the history of bullshit. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam Johnson: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: Welcome back to the show. Of course, you can follow us on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed, and become a supporter of our show through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson. We are 100% listener funded. The way we can keep doing this show is because of how generous you all are. Not only our listeners, but certainly our supporters through Patreon. So, we cannot thank you enough.

Adam: And to all our supporters, a reminder, if you haven’t signed up to Patreon and you can do so, there’s about 45 mini-episodes that we have that are exclusive to those who are on Patreon. So we appreciate the support there and we, we hope to maintain that as well. That helps underwrite the episodes themselves.

Nima: Nate Silver tells us that Joe Biden’s inconsistent political beliefs are in fact, a benefit. They’re quote “his calling card” and evidence that he “reads the room pretty well”. Venality, he tells us, is “a normal and often successful [mode] for a politician.”

Adam: Insurgent progressive groups like Justice Democrats shouldn’t call Biden out of touch with their base because, as Nate Silver tells us,“only 26 of the 79 candidates it endorsed last year won their primaries, and only 7 of those went on to win the general election.”

Nima: On Twitter and through his columns, high status pundit Nate Silver has made a career reporting on the polls and insisting he’s just a dispassionate conduit of the Cold Hard Facts — registered trademark. Like Joseph Smith or the prophet Muhammad he’s just channeling the holy word of — what else? — “data.” Silver is not really interested in expressing any kind of ideology he insists, only doing what he calls “empirical journalism.” Through this schtick however, a lot ideology winds up being advanced, unsurprisingly an ideology that reflects Silver’s own self-admitted “libertarian, liberal” bent.

Adam: To pull this off Silver has perfected what one Twitter account, @InternetHippo, refers to as “Pundit Brain”, whereby one forgoes fighting for things and rests on simply describing the world in a reductionist and oftentimes bleek manner. The main feature of Pundit Brain — something we’ve talked about on the show a lot which we call The Normative-Descriptive Shuffle — which is a rhetorical trick used effectively by Silver whereby conversations about values and policy and what is good in society are, without the reader really noticing, shifted to discussions about quote “just the way things are” in a world-weary savvy manner.

Nima: In this view, nothing is really worth fighting for on first principles, politicians should simply listen to the polls and adopt policies that reflect what is generally popular and uncontroversial. The goal of this particular rhetorical trick, and the spread of Pundit Brain in general, is inherently reactionary. By prioritizing a description of the world, rather than attempts to change it, politics becomes a pseudoscience, a sport to be gamed rather than a mechanism for improving people’s lives.

Adam: The spread of Pundit Brain has trickled down into liberal discourse more generally. Now, we are all some version of Nate Silver. Average political media consumers watch polls religiously, try to figure out who is quote unquote “electable” and what ideas are quote unquote “possible.” In lieu of advancing a candidate or agenda they believe in, voters themselves have become mini-pundits, not arguing for a better world, but trying to figure how best to quote unquote “win.”

Nima: To discuss this and more we’ll be joined later on the show by Nathan J. Robinson, Editor in Chief of Current Affairs.

[Begin Clip]

Nathan J. Robinson: He’s an apolitical kind of a guy. I think he would say he doesn’t really have much of a stake in politics. He doesn’t care very much about politics except like he likes the intellectual challenge of prediction and that’s one of the things that helps you understand why he’s totally fine with saying, ‘oh well this healthcare plan that would leave millions of people uninsured and would cause needless deaths but this plays well, so it’s the best bet.’ Because he’s just a betting guy.

[End Clip]

Nima: We’re going to start this episode with a little bit of background on Nate Silver himself. Nate Silver, of course, the American media’s favorite political soothsayer. Silver’s past can actually provide a bit of insight into how he got into this kind of punditry and what that says about his ideological origins.

Adam: Yeah, so whenever we do an episode on a specific person, it’s kind of ad hominem. We want to make clear that the shows that are about a specific person are never really about a person necessarily. They’re about a, a kind of broader ideological tic or broader audiological through line and in Silver’s case, as we discussed in the intro, the issue is really about how you shift discussions of policy and values and normative debates into conversations that are necessarily reductionist and I think inherently reactionary and bleak. So to begin with, a little bit of background here. Silver graduated in 2000 from the University of Chicago with a degree in economics, after which he spent four years working for the consulting firm KPMG. He somewhat famously at the time he had several newspaper articles written about him, he quit his job at KPMG to start doing full-time online poker. He claimed he hated his job and he really enjoyed the kind of intellectual gamesmanship of poker. The second thing he did after that was he invented a tool for forecasting player — this was sort of right in the uptake of Moneyball and kind of the scientification of baseball — he was on the forefront of that. He invented a tool called the Player Empirical Comparison and Optimization Test Algorithm, which really launched his career into a kind of forecasting guru.

Nima: The Moneyball-ification actually of, you know, not only sport, really sort of explains a lot about how Nate views things, right? So he sold this tool to Baseball Prospectus in 2003, joined the company about a year later as its executive vice president. At Baseball Prospectus Silver wrote a weekly column called “Lies, Damned Lies,” which of course comes from the quote that Mark Twain made famous about that there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics. Silver also co-authored the organization’s annual book of Major League Baseball forecasts.

Adam: When we say Silver views politics as a sport, we mean that literally. His first passions were poker and baseball and they sort of didn’t really hold his interest and he thought he could bring his kind of empirical data driven gaming approach to the world of politics and elections. In November 2007, Silver begin writing and political blogging at the Daily Kos using the pseudonym Poblano. His first post was, quote, “HRC Electability in Purple States” examined polling data on hypothetical general election match-ups in so-called “purple states,” finding that Hillary Clinton underperformed in those states — trailing Republican candidates by an average of 1.25 percentage points — relative to Obama and Edwards, who both led in purple states by an average of 8.5 points.

Nima: So at the Daily Kos, Silver writes about polling from an explicitly partisan perspective, I mean afterall it is the Daily Kos right? So, he wrote stuff like “Edwards also did the worst in Blue states … what that seems to suggest is that if Edwards is the nominee, particularly against a ‘moderate’ like Giuliani or McCain, the results could fall among somewhat non-traditional lines — more states will be in play. We might have to defend New Jersey, for instance, but maybe we could win Tennessee — stuff like that.” But nonetheless, Silver’s pro-Democratic Party, pro-Obama perspective rarely contained any substantive ideological content. Silver was always in “wonk mode” focused single-mindedly on forecasting elections and electability, with very little concern for actually the policy issues at stake. What affects politics would have on real people’s lives. And his very first Daily Kos post ended with this paragraph, which is actually quite telling and it’s this quote:

“If you’re a Clinton supporter, more power to you. We’ll have to work together to fight the propaganda onslaught in the general election, and to win back those voters that she might lose in swing states. However, I would urge you to think carefully about your vote, and I would urge those of you in the Dodd, or Kucinich, or Gore, or Biden, or Ron Paul camps to consolidate your support behind either Obama or Edwards.”

Adam: Yeah, well, it’s a good thing we didn’t get behind Edwards, in retrospect. On March 1, 2008, Silver launched FiveThirtyEight.com as a standalone site to cover the 2008 election. He revealed his true identity two months later in a post called quote, “No, I’m not Chuck Todd” unquote.If you recall the time Chuck Todd was in DC’s, he was this sort of the stats guy.

Nima: Yeah, yeah.

Adam: He has since been reduced to just doing a really sad kind of Tim Russert impression, but that was back when he was the stats guy.

Nima: In May of that year, this is 2008, good ol’ 2008, Silver really wound up gaining national attention for the first time, calling the very closely-watched North Carolina and Indiana primary races within two percentage points, well ahead of every other election forecaster. He gained even more attention when he almost perfectly predicted — this is, I mean this is the thing that really blew up his profile — perfectly predicted the 2008 Electoral College result in the Obama/McCain election, he missed it by just one electoral vote which, to be fair, was a Nebraska congressional district that Obama won in an upset and Silver actually didn’t even try predicting individual congressional district results, so his guess wasn’t actually incorrect, since he accurately predicted Nebraska’s statewide result. It was actually fairly impressive by those standards.

Adam: A year later, FiveThirtyEight’s Obama loyalism earned them the distinction of becoming one of the first blogs to receive a White House press pass, and the early FiveThirtyEight maintained its pro-Obama stance that was similar to his early days at the Daily Kos, and he spent much of the year after Obama’s election pushing pro-stimulus and pro-Obama propaganda. A year later, The New York Times licensed FiveThirtyEight in the midst of a larger blog acquisition binge, they did a similar licensing deal with Freakonomics as you remember. FiveThirtyEight quickly became one of The Times most-viewed verticals, bringing in hundreds of thousands of page views a day.

Nima: By 2012, Silver kind of repudiated his past overt support for Obama, really wanting to maintain this idea that he’s nonpartisan, he’s all about the stats. And in an interview with Charlie Rose that year, 2012, he said he actually didn’t even intend to vote in the 2012 presidential election, but if he did quote, “it would be kind of a Gary Johnson versus Mitt Romney decision” end quote. Silver described himself as quote “somewhere in-between being a libertarian and a liberal.”

Adam: In late 2013, Silver announced that he would be leaving The New York Times once the three-year licensing deal he had negotiated expired. FiveThirtyEight was bought by ESPN for an amount we don’t know. FiveThirtyEight’s new life at ESPN was supposed to involve applying data journalism to every area of coverage: sports, culture, and obviously politics. Last year, in a deal widely described as “unusual,” ESPN sold FiveThirtyEight for an undisclosed sum to its sister corporation, ABC News.

Nima: So that kind of gets us up to speed. What is missing here, although you can see it running through the threads of the kind of ebb and flow of Silver’s career, is what we were talking about in the intro, which is this idea that by simply presenting data-driven forecasting as an alternative to, you know, say more traditional political punditry, right? So say the tracking the horse race, following campaigns around the country, getting on the bus, being at those press conferences and those rallies, doing investigative journalism, like just follow the data. That’s the forecast, that will tell you everything. But doing that Silver’s kind of overall work demonstrates that forecasting itself is just punditry by another name and that what he is doing and what his site winds up doing is just more horse race journalism itself. I mean this is not mind blowing of course, but like the idea that somehow following the statistics is dispassionate itself reveals an ideology.

Adam: Yeah. Cause the thing is is that in reviewing Nate Silver’s work, and you look back, especially at kind of the peak smartest guy in the room, West Wing phase of like 2007, 2008 much of which was fused by Obama because Obama kind of was that candidate, I posed the question on Twitter back in August, which is Nate Silver, wrote a tweet saying, this is from August 26 he said, quote, “Is Warren still gradually moving up in polls? Very likely, yes. Is Biden gradually moving down? Quite possibly but not as clear. Is Sanders on a bit of an upward trajectory? Maybe, but even less clear. Have there been any sudden shifts in the past ~1–2 weeks? Pretty doubtful.” So it’s like there’s all these weasel words “maybe” “possibly” “pretty” and I’m reading this and I’m just like, why would you dedicate your life to that? Like what? None of that means anything. It’s just words. It’s just, you know, and this is really the thing here, which is that horse race in general is at best a massive time suck and distraction from substantive debate and at worst — I think possibly more likely — is really just a sort of overly cynical, bloated market for reinforcing the status quo. So you read this and I think what is the virtue of this? How is this valuable? Imagine dedicating your life to this schlock and that’s the thing is that there’s no, it’s not clear what is, I don’t want to be too sort of Socratic here, but what is the virtue of this? Why is it good? And I have yet to see an answer. And the reality is that horse race in general, and really the horse race is the issue here, is that it’s not clear what value it has. It’s not clear why New York Times and ESPN and ABC dumping all these resources into paying Nate Silver presumably millions of dollars and not paying people to provide analysis that is based on first principles or based on some sort of adversarial relationship with power or — god forbid — funding journalists who actually reveal new information. Right? I don’t know what the value is. I don’t know how it contributes to society. I don’t know how tea leaf reading polls in an incessant and increasingly granular way, I mean I’m not being rhetorical, Nima, you tell me, why is that good? What is the point?

Nima: As we’ve discussed on Citations Needed before, Adam, the idea that polling is not also self-fulfilling is something that is often not really talked about all that much. The idea that you know, FiveThirtyEight and Nate Silver predicted the 2008 election pretty much perfectly like electoral college wise, doing that then gave him this authority that when he speaks about polling it’s like, ‘ooh, then that’s what it’s going to be.’ Except it’s never been that way since. He got famous off that thing and like he’s able to do statistical analysis, which is fine, but he also comes from this very, as you said Adam, it’s very cynical and it’s very snarky and his entire schtick winds up being that which you could only actually do if politics didn’t mean anything to you, if you would never really be negatively affected by anything that happens. And so it’s almost like you never know when he’s being serious and when he’s not being serious. For example, there was a tweet he posted in January of 2019 saying this “Maybe Pelosi should offer to fully fund the border wall in exchange for passage of HR 1, the Democrats’ giant voting rights/campaign finance/anti-corruption bill. It’s her top priority and the border wall is Trump’s, so everyone gets what they want.”

Adam: Yeah, real galaxy brain stuff there.

Nima: Everyone gets what they want —

Adam: Except for the immigrants who are incited by a racist symbol for white supremacy.

Nima: Right except funding this ridiculous racist project like ‘everyone gets what they want?’

Adam: Like, nothing is sort of worth fighting for.

Nima: Right.

Adam: Again, it’s this, he’s like the last person on Earth, even Matt Yglesias has sort of come to terms with this, like he’s the last person on Earth who still thinks that we’ve reached the end of history. Like he hasn’t gotten the memo that we haven’t sort of decided on the primacy of the free market and US imperialism. And so there is Justice Democrats, which is a sort of grassroots organization that’s pretty good, they sort of back progressive challengers, sent out, this is from April and I think this is really insightful to his ideology. They said “Joe Biden is out-of-touch with the center of energy in the Democratic Party” and they had a graphic that said “Democrats’ Future” includes “Medicare for All” “Green New Deal” “Free college” “Rejecting corporate money” and then it had an image of Joe Biden saying “Past Votes” and it said “For Iraq War” “For Bankruptcy Reform Act” “For Mass Incarceration” “Against school desegregation”

Nima: Pretty clear ideological differences.

Adam: Yeah, so Justice Democrats is an insurrection group that’s trying to change the Democratic Party. Now, Nate Silver being the smartest guy in the room says quote, “It’s probably worth noting that while this group, Justice Democrats, calls Biden “out-of-touch” with the “center of energy” in the Democratic Party, only 26 of the 79 candidates it endorsed last year won their primaries, and only 7 of those went on to win the general election.” So.

Nima: Right. Don’t try and actually change anything.

Adam: Never try to change anything. That if you are — to put it in capitalist terms he’d understand — that if you’re a startup and you’re trying to take on a large corporation, if I can look at your first year returns and say, ‘oh, you lost the money and you’re getting out maneuvered by the large corporation, why are you bothering?’ Nothing should ever be tried ever. Right?

Nima: Exactly. That’s the whole point. It’s, there’s a reason why this past July Silver wrote, quote “Seems like the point of a debate should be to have the candidates who actually have a chance debate against one another.” End quote. This is the Democratic debates, obviously.

Adam: But who determines who has a chance?

Nima: Right. Nate Silver does.

Adam: That’s why you have the debate. Like there’s, there’s this rampant elitism in so much of what he writes where again, the least morally and intellectually interesting question in politics is describing the world the way it mostly is because it’s usually fairly obvious, right? The interesting question is like how do we change it? Why is it good? What is worth fighting for? What are the priorities we should have? And he’s just completely wholly disinterested in those questions. They just don’t interest him because that’s not a game, right? That’s not something you can sort of quantify and put in a ledger somewhere. And this would be sort of fine enough, but there’s a real trickle down effect that I’m, I’m certainly not going to blame this by any means all on Nate Silver, even mostly on Nate Silver. But what you see is, is you see this kind of gamification of politics trickled down into the average voter. And this is somewhat anecdotal. What I would submit that anyone listening to this as seen this where people will say, we got to listen to Joe Biden because he could win, that he’s electable. And we talked about this in our electability episode as well, which again are all these kinds of tautologies where people themselves have become little mini Nate Silvers where we, we don’t talk about who’s good or I like Warren’s plan or I like Sander’s ideas. We’re all trying to game a system.

Nima: Right. Right. What is the margin of error, right? That’s all that’s important.

Adam: And the prioritization of horse race, which you see Chuck Todd does this. Chuck Todd for the last four months on Meet the Press has been doing this extremely ideological progressive versus pragmatism dichotomy where he’s saying are progressives going to like get their wish list or they’re going to try to be Trump, which is a totally inherently and incredibly loaded-

Nima: Oh no, exactly. It’s a false, it’s a false choice, right?

Adam: And people begin to internalize that. People begin to think that they’re going to game some system. And you see this all the time and you see this when you interview voters, when you see this disparity, for example with Elizabeth Warren, where people will say, I personally think she’s great but she’s not electable. And it’s like, well, but the whole thing is circular. And so like I really think that the reason why pundits love people like Nate Silver is cause they talk about politics without talking about politics. And that is the, when you don’t want people to really talk about things that would just go to that which is bad, right? Cause then you would start, that logically leads down to the dangerous path of naming names and talking about who’s funding elections and who’s guilty. You want them to sort of look at it as, because again, the horse race by definition makes us all spectators, which is precisely the point.

Nima: Right. And that all we can do is try and bet on the results. Right? But it’s not actually our doing.

Adam: Cause what are you doing in a horse race? You’re not the jockey. You’re not the owner of the horse. You’re just fucking riding on it.

Nima: Right. And we’re certainly not the trainers, right? That’s exactly right. That is why it is called that. And so I think before we go to our guest, I will leave us with this. I want to preface this. I’m going to read a tweet from Silver from 2015. Plenty of people did not foresee what was coming in 2016. I don’t want to lay this all on the doorstep of Nate Silver, but this really speaks to what he thinks is possible and real and how that informs what he does with statistics, how he analyzes, how he views politics and how people interact with politics and how politics affects the lives of people. And this is a tweet from Nate Silver from July 18, 2015 and it’s this quote, “I’m mostly trolling but: Bernie Sanders has about the same chance to win as Trump so maybe HuffPost should cover him as “entertainment” too?”

Adam: Yeah. And it’s like how, how could you possibly know that far out how much of a chance someone has or what that even means? We’re describing the world, but also creating the worlds at the same time, which is the sort of point, right? We talked about this in the electability episode, and forgive me if I’m being redundant, but by saying what is the possible and creating the limits of possibility, you are necessarily-

Nima: Redefining what they are.

Adam: Yeah. You’re necessarily pushing the status quo. By preemptively creating the limits of debate and what’s possible you’re necessarily advancing a reactionary or conservative position, obviously.

Nima: Right, which just winds up being that everything has to stay the same.

Adam: More or less how it is because again, we’ve reached the end of history so why bother?

Nima: To discuss this more we’re going to be joined by Editor in Chief of Current Affairs, Nathan J. Robinson. Nate will join us in just a moment. Stay with us.

[Music]

Nima: We are joined now by Nate Robinson, Editor in Chief at Current Affairs. Thank you so much for joining us today on Citations Needed, Nate.

Nathan J. Robinson: Oh, thank you. It’s so nice to be here.

Nima: We’ve been talking about Nate Silver today. It seems to us that the story of Nate Silver as you and others have also observed, is kind of one of becoming what you most hate, the living embodiment of the axiom you either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain in that like his early work is very critical of the pundit class, letting their horse race coverage be informed by ideology. But since 2016 really this is mostly been his own online shtick. So before we get into some more specifics, can you just talk to us a little bit about maybe this tragic arc of Nate Silver and what it says about the specific political environment that he grew out of versus kind of what now exists in his own persona?

Nathan J. Robinson: Sure. Well, it’s not that tragic because he was never, he was never great, but like he’s definitely gotten much, much worse.

Adam: From mediocre to tragic. How’s that?

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah. Yeah. Right. I mean like, I don’t miss Nate’s, I don’t feel like we lost much. But, so, he first became famous, right? Because he called 49 states right in the 2008 race. And he became known as someone who was more careful as a maker of political predictions and as a statistician than many other pundits. He was more evidence-based. He got away from gut feeling and he started trying to figure out, you know, which polls are reliable, which aren’t and aggregate things carefully and well using sound judgment. And he was very successful doing that. And he wrote a book in 2012 The Signal and the Noise: Why Some Predictions Fail and Some Don’t. And that book is really a book about humility as a predictor, as a forecaster. And it’s about the errors that people make, the way that ideology can influence people’s judgment and how to be more humble and careful in the calls that you make. And there are parts of it where you can see that he thinks of himself as a person free of ideology. Right? And he’s very critical of those who have ideology. He uses the kind of the old hedgehog and the fox metaphor where he says, you know, I always forget which is which but like —

Nima: The hedgehog knows only one thing.

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah. The hedgehog knows one thing and he’s like very critical of the hedgehogs. Right? And the hedgehogs are like the ideologues. These are the people with a, they’ve got, you know, strong political beliefs that influence their view of the world. But he’s a fox. He takes lots of different sources of data and he pieces them together and as a result, he’s much more accurate cause he’s more of a scientist. And then throughout 2015, 2016 you really see where hubris takes Nate Silver because he thinks of himself, he’s been anointed the king of data. That guy who gets it right. The Nostradamus of the American political scene. And yet he starts to tweet things and write things that in retrospect begin to look idiotic. I mean, he really strongly argues that Donald Trump has no chance even when the polls support, Donald Trump was actually a very strong in the polls from the moment he entered the race. And in August 2015 Nate Silver said that Donald Trump was winning the polls, but he was losing the nomination. He issued a prediction in August of 2015 Trump won’t be the nominee. He said, Trump is, he called him the Nickelback of presidential candidates. He super popular with a few people, but most people just hate him. He said, don’t take the Trump surge seriously. He said this over and over and over. And of course he was completely wrong and completely blindsided. And he looked back on what he did after he was wrong and he said, what I did was I had made the mistake of becoming a pundit and I had just gone with the kind of gut feelings that I was critical of others with going for. And that’s true. That’s exactly what he did. Unfortunately, he’s now doing exactly the same thing again. And if you look at Nate Silver’s tweets these days, you see right now he’s, it changes constantly, but right now he’s confidently predicting that Elizabeth Warren as the favorite to win the Democratic nomination but the top three are Biden, Harris and Warren, and they’re the three with a chance. And he’s doing so, now Warren’s not leading the polls generally, so he’s doing so on the basis of, once again, his judgment and his judgment is deeply flawed. That’s what we saw in 2015, 2016, that’s what we can see now. And so my position is that basically we should just ignore him because he’s gotten completely detached from his, he still calls himself a quote “empirical journalist” but I don’t think there’s anything empirical about it.

Adam: Yeah, so there’s this thing we talked about earlier in the show, which we’ve referred to before we call the Normative Descriptive Shuffle, whereby one sort of inserts a descriptive observation, typically a poll showing how some really crappy right-wing idea is actually very popular into a conversation that’s really a values based conversation or even sort of a normative policy conversation. Silver kind of does this a lot. This is popular with Ezra Klein, Matt Yglesias, you’re kind of typical data journalist crowd, where you’ll sort of say something’s bad ‘Biden’s racist’ and say, well that, you know, ‘Democrats love Biden’ and it’s like, well, okay, but that’s not really what we’re talking about. And Silver is kind of a greasy operator in this way in that he consistently kind of launders what is clearly his opinion, as you touched on before, through some kind of empirical reductionist observation about popularity or whether or not something is this sort of close cousin of popularity, which is feasibility, that it is possible. How much do you think that this sort of, you said empirical driven journalists or data-driven journalists, not just with him but in general, a little bit of a way of kind of laundering what is effectively conservative ideology for lack of a better term?

Nathan J. Robinson: Well, I mean we could call it conservative, we could call it centrist, in Nate Silver’s case, I think he’s a neoliberal, right? I think he is from the Obama wing of the Democratic Party. And yeah, I was just combing through the recent tweets and one of his big ones is Biden’s healthcare plan is more popular than Medicare For All. And he said, well that’s, you know, first because one reason is because you don’t, nobody explains Medicare For All to the people that they’re polling. And usually they say, how would you like losing your insurance and paying a bunch more in taxes? And then people go, well, that sounds awful. And then they go well see if you really explain the details of Medicare For All then people hate it.

Nima: And they’re like, what Biden’s plan? And they’re like, not that. And they’re like, okay, I like that.

Nathan J. Robinson: Oh fantastic. Please give me that. And that’s used to prove that moderation is pragmatic as well as being correct. And in fact, there was another one that I saw that was kind of in this vein recently where he said that, um, the idea that moderates are more electable is backed up by a lot of political science research. Now, he didn’t cite the political science research that proves that. He says this a lot. Like he’ll say like, ‘oh, there’s tons of research on this,’ but he won’t tell you what the research is. And now it’s Twitter. But also one of the reasons that you can’t cite the research is because it really is almost impossible to prove that quote “moderates are more electable.” Because if you think about what it would take in order to prove that, you’d have to control for all the variables other than the variation in ideology. So you’d have to take two candidates who are like equally dynamic and charismatic, equally well funded, and had basically like an equal shot in everything except one was to the left of the other one.

Nima: Right.

Nathan J. Robinson: And you’d have to run that over and over and over.

Nima: The media covers them exactly the same.

Nathan J. Robinson: And so it’s very, very difficult to prove that moderates are more electable because we haven’t really had vibrant left candidates for a long time. So it’s not clear what research you could even pull up to show that like a moderate is better against, for example, against Donald Trump. We didn’t run both Clinton and Sanders and then see what happened. We just ran Clinton. So how can you possibly show that? But he says it as if it’s, I mean, he says science, it’s political science. This is hard data, but it isn’t hard data at all. And you don’t notice the way that your own preferences are filtering into your assessment of the empirical facts.

Adam: It’s such a bleak view of politics too. It’s like, what are we doing here then? You know, the goal is not to convince people or to use the bully pulpit of elected office or the campaign it’s sort of to just put your finger to the wind, see which way it’s blowing. And it’s so depressing. It’s like the idea that you can get Medicare For All as this sort of pariah issue until Sanders popularized it in many ways and others of course had done it before and had done it obviously before him, but he kind of brought it into the mainstream and now it’s, it’s fairly popular even among Republicans and it’s like, but if Nate Silver had his way, we would still be doing the thing that was popular in 2002 ad nauseum.

Nathan J. Robinson: Well, this is why there’s a huge flaw in the entire approach because even if we say that he’s a pretty good statistician, it’s very difficult to forecast unknown unknowns and you can take a snapshot of where things are at any one time but one of the things we’ve learned about politics in the last few years especially is just how much is unknowable and unpredictable. And, you know, the best mathematician in the world can’t tell you the answers to certain questions. And so if Bernie Sanders had looked at polling in 2014 when he was trying to decide whether to get into the race and he would have gone and probably did say to himself, you know, ‘I have almost no chance of beating Hillary Clinton.’ Of course it turned out that polls change, they change when you expose people to a message, they change when you run a really good campaign. And so often the question is not what do things say now, but what things could alter in the future and what is going to alter those? And Nate Silver really, really doesn’t have anything to say about that. I mean basically the thing he is saying now, the reason he thinks Elizabeth Warren’s going to win the nomination is it’s just a pundit observation. He says, Elizabeth Warren has the best chance to unite the left and the center of the Democratic Party. She has the largest possible constituency and that’s a story you can tell and you can kind of see how it might be plausible, but I don’t know that that’s true at all. It could be that like it turns out that Bernie Sanders is running a very good ground operation and that people really trust him after a long career. You know, I don’t know. I can tell a bunch of different stories and the only way that we know which one of our different stories about what’s going to happen is true, is to find out which one of them turns out to be true because he doesn’t know. And he’s saying it, he says like Elizabeth Warren has the best chance. Like that’s just, that’s just math. I’m just using math.

Adam: I made this point repeatedly in 2016 and I guess I’m making it again now we’re sort of doing this over again, in 2015, you know, Jamelle Bouie wrote two different articles saying Trump can’t possibly win, obviously David Brooks did and I just, every single one of them, I wouldn’t say Trump is going to win, but I’d say you don’t know. And people get paid a lot to talk about politics and they sort of have to have a prognostication, but like why? Like why are we all in the business of making these predictions when we have no fucking idea? Why can’t people just say ‘I don’t know?’

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah. So in February of 2016 the consensus was that Trump wasn’t going to win. And I wrote an article saying that he probably was going to win. And the way that I framed it was not, I have a bunch of polling data that you don’t have. What it was was I have a different story that I can tell you now, see if you find this plausible? And I said, here’s what’s going to happen when Trump runs against Clinton. Trump is gonna run to Clinton’s left on the Iraq War. He’s going to highlight all of the qualities about her that people don’t like and she’s going to have a very hard time defending herself. He’s going to make criticisms of her that you will realize are valid because they’re true and he’s going to have a very successful economic populist appeal that she is going to be unable to counter because she’s associated with Wall Street and all of the horrible aspects of the political class that people hate. That’s what’s going to happen. In the event, that is what did happen. Now is not because I had, as I say, I didn’t have access to any better data, but it was just, there was a different story you could tell and if you knew more things about the world then people like Nate Silver know then you would understand that this story resonated. One of the reasons that Nate Silver is so limited in what he could tell you is because he doesn’t really understand the world very well. He understands numbers very well and he understands polls very well, but like he mocked a guy in 2016, there was this right-wing pundit who said Trump was going to win and everyone was mocking him and Nate Silver mocked him because he said, ‘well, I don’t see any Hillary Clinton yard signs in Michigan, but I sure do see a lot of Trump yard signs.’ And that was a, you know, anecdotes are data, they are data points. They’re not systematically collected data, but they are pieces of evidence and a lack of enthusiasm could well show itself in the fact that like nobody’s putting bumper stickers on their car and they’re probably not going to go to the polls either. That wasn’t actually a thing to really mock. It was just qualitative piece of data from the world. The same way, if you went out and you started talking to people and you realize that they weren’t very enthusiastic or, or they were going, ‘yeah, I’ll probably vote, but I don’t know if I’m going to vote.’ It’s qualitative data, but it could tell you a lot. So, you know, you have to get away from your computer and stop just to, you know, refreshing FiveThirtyEight in order to have a better predictive power.

Nima: Right. Because it seems like the reliance that FiveThirtyEight has on data, on polling, and we’re just going to crunch the numbers and we will tell you who is going to win. They do this now for the Oscars, they do it for whatever, right? Everything. But it’s missing what you’re talking about, which is this core component of like of narrative, of societal and cultural narratives that are not adequately reckoned with in these data points. And so I think that, you know, what then winds up happening is Nate Silver’s since 2008 like gotten a lot wrong. He keeps getting things wrong. And yet the reaction that he has to that is then moving the goalposts. And you’ve actually written about this, Nate, a bit, and forgive me for quoting you at length back to you-

Nathan J. Robinson: By all means quote me.

Nima: So you wrote in 2016 that quote:

“The myth of Nate Silver’s continued usefulness is based on a careful moving of goalposts. His initial claim to fame was based on number of states correctly predicted. But in 2016, if we measured by that number (especially if we subtracted the states whose outcomes were most obvious), Silver wouldn’t look good at all. So now we’re invited to focus on a different statistic, the percentage chance of an overall Trump win. Conversely, when it’s the percentage chance that goes wrong, Silver reminds us how many races he called correctly. Like a television psychic, Silver is able to carefully draw your attention to that which he gets right and ignore that which he gets wrong.”

So, beyond just kind of, like, dunking on Nate Silver, what lessons do you think can really be gleaned from this wrongness?

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah, so yeah, I think I was completely right there. I stand by that. Um, it’s true that in 2008, right, everyone’s like, ‘oh, he got almost all, 49 in 50 states’ and then in 2016 he didn’t get any. But he said, ah, look, I was less confident in Hillary’s victory than many other pundits. And that’s actually true, right? There was a guy at the Princeton Election Consortium who was saying she had a 99 percent chance of winning. The Huffington Post criticized him for thinking she had anything less than certainty. And Nate Silver, and so one thing is he’s quite cautious. He hedges a lot. And I think hedging is a good thing. But what it means is that you’re less useful than, there’s no real way to be useful, but he makes a lot of contradictory statements. Like at one point he said like Trump was going to win.

Nima: When his job is literally not to hedge.

Adam: Yeah. ‘Cause at some point it is not meaningful.

Nathan J. Robinson: Right. So he said, oh Hillary Clinton, I forgot what the ultimate percentage he gave her but it was lower. And he said, ‘ah so I gave her a lower chance than other people so I was better predictor.’ But you still missed the whole story. You still thought she was going to win. And he’s still got a bunch of races wrong in the primaries where he missed, for example, the Michigan upset, where Bernie Sanders defeated Hillary Clinton. He thought that Hillary had a 99 percent chance of winning Michigan. Now I knew people on the ground in Michigan who said Hillary’s chances of winning in Michigan are much lower than people assume. ‘She doesn’t have a ground operation here. Bernie is doing really, really well. Everyone in rural Michigan Loves Bernie. They’re all gonna turn out.’ So if you had qualitative data, you would understand that that number was wrong. So it is actually possible to do better than he is doing. And so that’s I think the big lesson here, right? Interestingly, like in his book, he does kind of advocate this approach. I think there’s one anecdote where he’s talking about how some guy improved his political forecasts of candidates’ prospects by doing interviews with the candidates. And like there was a candidate where he was forecasted to win but in the interview with the candidate, something seemed fishy. It seemed like the candidate might have something to hide and sure enough, a scandal came out and destroyed the candidate. And so if something seems fishy, you kind of lower that candidate’s odds. And because you have that qualitative data from the interview of like, which is just like a vibe, you got a bad vibe, that vibe actually led you to make a better and more cautious prediction. And that’s kind of, it’s a frustrating truth, but it’s important if you want to understand politics and make good predictions, is that like feelings can be kind of important. The unquantifiable really matters a lot. The reason that I did quite well in 2016 with the election was because like I just got a really, really bad feeling that people were too confident, they didn’t really understand, they weren’t really thinking about how things could go wrong and there seemed to be these factors that they weren’t taking into account in their stories. And that’s also true for people who predicted the financial crisis correctly. You know, you might notice that people seemed really not to be thinking about what would happen if everyone defaulted on their mortgages. And you might go around and talk to homeowners and people say like, ‘yeah, I don’t know how I’m going to keep paying this.’ And it might not show up in the numbers that you have, but if you want to beat, if you want to beat the forecasters, having a better knowledge of the, I’m not saying the emotional reality, cause that sounds very squishy, but it’s often quite true is that you can be, emotions can offer you sometimes a better guide to empirical reality than a set of numbers that have been collected by people who don’t really understand how other people feel and think.

Adam: I think the damage of a Nate Silver, as it were, is actually not so much limited to him, which, you know, we’ve kind of established is sort of just a kind of grumpy rich guy who doesn’t like lefties, is that I do think there’s something that comes up, which we talked about called Pundit Brain, where like your average voter becomes Nate Silver, where we now have this game theory where people, we talked about this in our electability episode where people start to try to play pundit in play prognosticator by guessing who’s electable. And this shows up in some of the polls. Specifically, I think it’s hit Elizabeth Warren the hardest where people say she’s popular and they like her, but then they’d say she’s not electable based on some nebulous idea of electability. To what extent do you think you’re going to have to sort of do some guesswork here? Do you think that the Nate Silver-ification of sort of the average person, and then of course he’s not the only one responsible for it, this has been a thing for a while now, but the average person getting a case of Pundit Brain can actually have a deleterious effect on how people view politics and the participation in politics.

Nathan J. Robinson: Well, it’s devastating, you know? I mean you also, you become a spectator and you start, this was the thing that happened in 2016 was everyone was refreshing FiveThirtyEight all the time. That became kind of a thing as I’m refreshing FiveThirtyEight to see what’s changed and then what you become is you are a recipient of the numbers rather than the creator of the numbers. And this is very damaging because it has a status quo bias, as we talked about, whatever the numbers are, all I can do is sit here helplessly and hope that ticker goes more towards blue. So I just interviewed a guy Shahid Buttar, who’s running against Nancy Pelosi in San Francisco for Congress — he’s awesome — and he ran against her last time and got about 8 percent of the vote. And you might say, ‘oh, he’s not electable, he’ll never beat Nancy Pelosi.’ But that’s a self fulfilling prophecy. Look at AOC, right? You could have said to AOC and people obviously did, ‘you’ll never beat Joe Crowley because incumbents,’ oh, we have a formula, right? The political scientists can tell you like an incumbent with this much money in an economy like X, they always win. I mean, they have lots of things that they can tell you like that. And she had to defy that and she had to say, ‘well, f the polls, f the funding difference, I’m going to go out and do every possible thing it is to beat him and then just see what happens.’ And she won. It was a massive, stunning upset that forced people to reevaluate the received wisdom. Trump’s victory should force people to reevaluate the received wisdom. And so what you need to do is you need to find those things where the received wisdom could be wrong and you need to figure out how you change it. So the theme of the article was, do not say he can’t win because in saying that he can’t win, you’re going to make it happen that he can’t win. You’re going to make it that much harder for him to win if people assume it. And so what you have to do is say the future is unknowable. I have no idea whether he could win because I don’t know the future because I’m not a prophet. The Republicans, Eric Cantor, who was the speaker of the house, he got thrown out by a Tea Party person on the right. It’s perfectly plausible to me that that could happen on the left. It obviously faces formidable obstacles, but I can envision the headline in my mind, speaker of the house thrown out after 30 years in stunning upset. I can envision it. I don’t know whether it’s going to happen, but I certainly don’t want to accept the existing state of conventional wisdom as a fixed, immovable reality because then what point is there as to joining a political movement as we’ve said?

Nima: But it’s also the element of both horse race punditry in general, but really just in this specific case, talking about predictions, based on data, based on polling that those predictions themselves and you’re kind of alluding to this, Nate, the predictions themselves change the next prediction. Like there’s no neutral ‘oh, we’re gonna look at the polling and the predictions up on this big board but by us seeing that it has no actual effect on the people believing the things that they believe and thinking that they’re going to do the thing that they’re going to do.’ Like no, it actually does saying so and so is unlikable again and again and again and again either makes more people think that they’re unelectable and look to other people because it’s already been determined or conversely can also serve as a galvanizing call to action. Like fuck that deplorable thing. Leveraging something that has been thrown at you and just kind of working to then undermine that given ending that you’ve been told is going to happen. So like these predictions actually do have effects on the actual next poll.

Nathan J. Robinson: You know what Nate silver’s said recently? He said, um, ‘I don’t see why we don’t just have debates for the candidates that have a chance of winning.’

Adam: Right, the whole point.

Nathan J. Robinson: Well, that’s interesting. You’re deciding. What about the chance for people to look at the candidates and figure out which they think have a chance of winning.

Nima: That’s literally like hating on the idea of democracy.

Adam: Oh no, he, yeah, he has runaway contempt for democracy.

Nathan J. Robinson: Well, we set the chair. Oh, these are the ones that have a chance of winning because these are the ones we’ve showed you, by the way, we’re not going to show you any of the others. Think back to Ralph Nadar, right? We’re not going to show you Ralph Nadar because he doesn’t have a chance and you’re never going to see him and therefore he doesn’t have a chance. Again, this kind of self fulfilling thing where like people only find out about candidates through the media. That’s the, I mean nobody, very few people are going to run into these candidates in their day to day life. They find out because these are the people that they’re presented with on the televisual. So if it’s, so he’s just calling for limiting the ones who are presented to people. So I think, yeah, obviously, now it’s easy to say like, I think we all want like half of the sort of miscellaneous white man candidates off the stage, right? Because they’re just-

Nima: Right because it’s exhausting and it’s, it’s exhausting to like cover everything.

Adam: But ultimately, you know, it’s certainly better to err on the side of having more than less.

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah. I mean it’s so happens that they’re all terrible, but if there were someone who were quite good, we would want that person to at least have an opportunity to present their case to people so that they could make a decision.

Adam: Yeah, you definitely see the whole self fulfilling prophecy thing more in its most essential form when you see the post-debate spin where there’s the debate and then everyone goes on their panel and says who won and then later everyone’s like, ‘oh, so-and-so won.’ And I’m like, well yeah, there’s, there’s some objective criteria but a lot of that’s just informed by who the pundits told you won. You saw that a lot with Bernie and Hillary where it would be like ‘Hillary won.’ ‘Hillary won.’ It’s like, well, I, okay? I mean-

Nima: Right. Like I didn’t agree with anything she said so, okay?

Adam: But there’s some like, yeah. But yeah, then you get into the kind of meta meta of like who did well, we’re again, we’re all just playing the part of Stephen A. Smith and some guy at ESPN, right? Sort of gaming it.

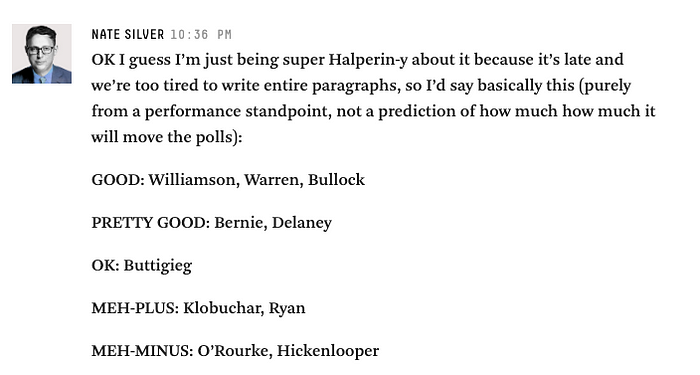

Nathan J. Robinson: Well, the debates, I, when I watched Trump debate Hillary Clinton, my reaction to watching Trump debate Hillary Clinton was, oh my god, he’s better than I think. She’s not doing very well against him. She should be creaming him, but she’s not. But the people I was with said, ‘wow, she really destroyed him.’ And Ezra Klein ran an article that said the debates left the Trump campaign in ruins as if like debates are the campaign. Right? And she said the things he agreed with. And Nate Silver had a thing after the July debate where he said, I dunno if you saw this, but he ranked the performances of people using the highly objective ratings: “Good” “Pretty Good” “Okay” Meh-Plus” and “Meh-Minus.” Now I don’t know the difference between “Good” and “Pretty Good.” I don’t even know which one of those is better.

Nima: (Laughing.)

Adam: Oh yeah. Wait, wait. Hold on. Wait. Which one is better?

Nathan J. Robinson: “Good” is better than “Pretty Good.” I think. Um, and “Okay” is better than “Meh-Plus” which is odd to me because I think meh and okay are kind of synonyms.

Adam: Why not just give them numerical values or the color scale that Homeland Security used?

Nathan J. Robinson: Well, this is science. This is political science.

Nima: Right, exactly. I mean, haven’t you ever heard of meh-plus and minus?

Adam: My apologies.

Nathan J. Robinson: And he calls himself an empirical journalist.

Adam: This is an extremely absurd question, but I want to ask you this question because I’m curious to sort of tease out which way you land on this. If I was to create a world whereby which under the Johnson regime all polling and all horse race was illegal and everyone had to talk about politics and specifically, oh, it’s a matter of first principles and normative terms, do you think, let’s say that had to happen over the next year, do you think our body politic would be worse or better than it is?

Nathan J. Robinson: Oh better. That’d be great. Wouldn’t that be great if we had no idea who was ahead? If we had absolutely no idea who was doing well and who wasn’t. And it was a surprise on election day.

Adam: Because you’d have nowhere to go really then to about what you thought was good and bad.

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah. And his entire, I mean Silver would have to disappear, which would be a bonus because his entire Twitter feed is horse race stuff. It’s all who’s up, who’s down, who’s gaining.

Adam: The most egregious example, Ryan Grim was criticizing Biden for being venal specifically that he was corrupt and that he was letting big donors inform his policies. And Nate Silver said quote, “His calling card is also that he reads the room pretty well and is pretty open/transactional about adopting his views to reflect the consensus of D voters and leadership. It’s not, say, Warren’s approach, but it’s a perfectly normal (& often successful) one for a politician.” So he sort of takes this thing that we would normally consider bad — arbitrarily just randomly changing your opinion based on the whims of donors — and says ‘actually it’s good’ and I feel like that that right there is the most essential Nate Silver moment right there.

Nathan J. Robinson: Right. I would agree with that. There’s so much of that where he takes qualities that are just repulsive and goes like, ‘well it gets you elected,’ which you go like, well people have gotten elected who have done that. That’s certainly true. Whether having some principals would hurt you or maybe it would make it even better for you is an open question. It goes back to that thing that you mentioned at the beginning. This conflation of taking things that you’re fine with or you think are good and suggesting that the data recommends that you do them, even though that’s not actually an inference that you can rationally make. One important point is that, I think Doug Henwood is the one who cited the fact that Nate Silver once said that he didn’t give a shit about politics, which I think tells you a lot. He’s an apolitical kind of a guy. I think he would say he doesn’t really have much of a stake in politics. He doesn’t care very much about politics except like he likes the intellectual challenge of prediction and that’s one of the things that helps you understand why he’s totally fine with saying, ‘oh well this health care plan that would leave millions of people uninsured and would cause needless deaths, this plays well, so it’s the best bet.’ Because he’s just a betting guy.

Nima: Well, because also you can only do what he does — and it’s not just him, a lot of other people do this — you can only do that job of kind of horse race prognostication soothsaying in a way if your life won’t change at all regardless of the outcome. Being so removed from the actual issues being discussed and their potential consequences that it just does stay Moneyball, you know, and I think that he’s like a perfect example of that.

Nathan J. Robinson: What do you care about? What are you invested in? The answer is nothing. I mean, I, you can look through his Twitter feed and prove me wrong, but I really think that’s what you get. And that’s true of so many pundits. Aren’t you suspicious of anyone for whom politics is fun?

Adam: Yeah.

Nathan J. Robinson: Like one reason I like Bernie Sanders is that he doesn’t seem to be having fun. He seems to resent having to do it.

Adam: No, that’s his most endearing quality. He is entirely incapable of sentimentality.

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah. He’s pissed!

Nima: Right, like this stuff might actually fucking matter.

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah. I’m not having fun.

Adam: Maybe that’s why people who make less than $30,000 a year like him.

Nima: Well, I think we should leave it there. Nathan J. Robinson, Editor in Chief at Current Affairs. Nate, it has been so great to talk to you today on Citations Needed.

Nathan J. Robinson: Yeah. Anytime. Great to talk to you.

[Music]

Adam: Yeah. I mean, I, you know, I sort of say this somewhat rhetorically, but it’s like, I really, I think if you did run two permutations and one had polling and one didn’t, I would think that the one without polling would almost certainly be considerably better. I’m not sure because it’s all sort of meant to game everything right?

Nima: Right. You’re like projecting a future that doesn’t have to be certain, but making it more certain by projecting it.

Adam: Yeah. It’s like this weird thing that happened in the run up to the November 2016 election where Clinton’s people were saying, ‘oh, we’re like a shoo-in we’re gonna win.’ Not all of them, but most of them. And I’m thinking like, why do you want to say that? What would be the point of that other than just sort of suppressing turnout, which is I think, and I don’t have evidence to support this, but I suspect, and I apologize for that, but I suspect that that may have informed some of the depressed turnout because the assumption was she was going to win and so why bother? Right? And, and I’m not sure why as someone running for office or running for polling, I mean I get that you’re trying to like fight a media narrative that your candidate is dwindling and you have to kind of address the sort of meta meta voter psychology of electability that you sort of want to trump good polls early. But within the four weeks before an election, I don’t see any fucking point at all in talking about polls ever because (a) it can only breed complacency and (b) who cares? Like what difference does it make? Like how is this going to convince someone? How is this gonna make whatever the proverbial undecided last minute voter, how is it going to make them come to Jesus? And it’s not clear to me how any of that does.

Nima: Well because I think part of it has to do with pushing group think, right? It’s like this weird kind of statistical bullying which is like ‘so and so is up by eight points.’ And so if you’re not there, you’re like, well like what am I getting wrong? As opposed to investigating actual reasons why you would not be in line with someone.

Adam: One theory that has been advanced by Silver and others that I think is probably true is you have this kind of like underdog bias where there’s a sense that there’s an underdog and the media will sort of either consciously or subconsciously either through accident or conspiracy will begin to kind of tip the scales and be like, ‘oh’ I really think you saw that in the last because it is absolutely true that the coverage of Clinton was way overwhelmingly more pro-Clinton in the same but in the sense that this is Trump and we’ve talked about this before, it is objective true the media was biased against Trump but the media is also biased against cancer. Like it is objectively true but then in the last week and a half after the Comey letter there was this bizarre corrective that I think ultimately cost Clinton the election that they somehow needed to like show how serious they were.

Nima: By really scolding her right? By having that be a really serious problem.

Adam: Yeah. And of course it was a total non story though, which we’ve talked about before and don’t need to get into, but I do think, but that was largely driven by the polls. It was driven by the assumption that the polls had shown she was going to overwhelmingly win and that we were all now safe to like punch Clinton to show how serious we were.

Nima: Right. Because at that point, what the polls said is that nothing was actually at stake.

Adam: And I think that’s partially why Comey himself did all that posturing-

Nima: Did it? Oh absolutely.

Adam: Because yeah, he’s like, ‘oh, it’s not going to affect the election because she’s a shoo-in.’

Nima: ‘It’s not going to matter and I wind up being more serious, nonpartisan, I can’t be accused of withholding something until after the election.’ Yada, yada, yada. When actually relying on polls to tell you what’s a foregone conclusion already was part of the problem and why cancer was then made president.

Adam: Right.

Nima: So that will do it for this episode, always ending positively Adam.

Adam: Yeah always.

Nima: That will do it for this episode of Citations Needed. Thank you everyone for listening and supporting the show. You can follow us on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed, and become a supporter of our work through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson. We cannot thank you enough for your support. We are 100 percent listener funded. It keeps our show going and an extra special shout out, as always, goes to our Critic-level supporters. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: Citations Needed is produced by Florence Barrau-Adams. Production consultant is Josh Kross. Production assistant is Trendel Lightburn. Research and newsletter by Marco Cartolano. Research and writing for this episode by Ethan Corey. Transcriptions are by Morgan McAslan. A very special thanks to Alex Cox of Cards Against Humanity for your generous support. The music is by Grandaddy. We’ll catch you next time.

[Music]

This episode of Citations Needed was released on Wednesday, September 18, 2019.

Transcription by Morgan McAslan.