Episode 146: Bill Gates, Bono and the Limits of World Bank and IMF-Approved Celebrity ‘Activism’

Citations Needed | October 27, 2021 | Transcript

[Music]

Intro: This is Citations Needed with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson.

Nima Shirazi: Welcome to Citations Needed, a podcast on the media, power, PR and the history of bullshit. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam Johnson: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: You can follow the show on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed, and become a supporter of the show through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast. All your support through Patreon is incredibly appreciated as we are 100 percent listener funded.

Adam: Yes, please, if you can help us out on Patreon it helps keep the show sustainable and keeps the episodes themselves free for our listeners, but of course we do have patron-only content for those who help us out there, short little News Briefs, newsletter, we do AMAs and also live shows as well there so any help there is greatly appreciated.

Nima: “Feed the world.” “We are the world.” “Be a light to the world.” Every few years, it seems, a new celebrity benefit appears. Chock full of A-listers and lofty taglines, it promises to tackle any number of the world’s large-scale problems, whether poverty, climate change, or disease prevention and eradication.

Adam: From Live Aid in the 1980s to Bono’s ONE Campaign of the early 2000s to this year’s Global Citizen Live concerts, televised celebrity charity events, and their many associated NGOs, have enjoyed glowing media attention and a reputation as generally benign, even beloved, pieces of pop-culture history. But behind the claims to end the world’s ills lies a cynical network of funding and influence from predatory financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, multinationals like Coca-Cola and Cargill, soft-power organs like USAID, and private philanthropic arms like the Gates Foundation.

Nima: This arrangement really reached its nadir from the turn of the 21st century until today, largely in response to outrage from anti-Pharma and anti-poverty activists from the global south and anti-globalization protesters in the 1990s. Spearheaded by Bill Gates, the Bono-Gates-World Bank model gained virtually unchallenged media coverage as the new face of slick, nonprofit “activism”, in opposition to the unwieldy, anarchist-y and genuinely grass roots nature of the opposition it faced on America’s TVs each time there was a G7 or WTO meeting.

Adam: While this celebrity-NGO complex purports to reduce suffering in the Global South — almost always a monolith and mysterious place called quote-unquote “Africa,” to be more specific — suffering on a grand scale is rarely decreased. Rather, it adheres to a vague We-Must-Do-Something form of liberal politics, identifying no perpetrators of or reasons for the world’s ills other than an abstract sense of corruption or inaction.

Nima: Meanwhile, powerful Western interests, intellectual property regimes and corporate money — all the primary drivers of global poverty — are not only ignored, but held up as the solution to the very problems they perpetuate.

Adam: On today’s episode, we’ll study the advent of the celebrity benefit and the attendant Bono-Bill Gates-Global Citizen model of activism, examining the dangers inherent in this approach and asking why the media aren’t more skeptical of these high-profile PR events that loudly announce, with bleeding hearts, the existence of billions of victims but mysteriously are unable to name a single victimizer.

Nima: Later on the show, we’ll be joined by two guests. The first, returning to Citations Needed, is Jason Hickel, economic anthropologist, professor, author, and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. He is Associate Editor of the journal World Development and his most recent book is Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, published last year by Penguin.

[Begin Clip]

Jason Hickel: To me it’s amazing that Gates gets away with sort of portraying himself as this cuddly wise grandfather in wool sweaters who cares about the poor, because the wool sweaters, by the way, are clearly a PR tactic, because let’s be honest, he’s a hard nosed capitalists who cares primarily about capital accumulation. That has always been for him the bottom line, and his primary strategy for a couple of accumulation is to lock up intellectual property, create monopolies, and extract rents.

[End Clip]

Nima: We will also speak with Jaume Vidal, Senior Policy Advisor at Health Action International. Working at the intersection of intellectual property rights, access to health technologies and human rights, he leads HAI’s European advocacy on innovation, transparency and trade.

[Begin Clip]

Jaume Vidal: I think the problem with this charity-based model is that it does nothing to address the causes of the problem, and it does not really seek workable solutions in the sense it only perpetuates the problem.

[End Clip]

Adam: So on May 7, we did a News Brief on Global Citizen, specifically their upcoming Vax Live concert, and their broader inaction or aggressive indifference to the call to make a global vaccine patent waiver. So that was May 7, we did an episode on them. There’s so much more to unpack on this topic, Nima, that we really wanted to sort of do its own episode because it is part of a broader cultural and ideological regime that’s really been in place for about 20 years, but of course it has its predecessors before that, but sort of the broader kind of Gates-NGO-Bono model we’re talking about in this episode really was, I think, exposed in that moment last spring. Although of course, it’s still not really supporting a patent waiver, despite doing so nominally, which we’ll get into, and it was part of a much broader kind of cultural and media and PR regime that had developed over the past 20 years or so, and we thought it really deserved its own episode, because it’s still very much with us today and gets absolutely zero critical media coverage. I mean, it wasn’t, you know, Bill Gates didn’t even receive meaningful negative political coverage other than Linsey McGoey’s book for Verso, who was our guest we had on our Bill Gates episode, gosh, three years ago, that she wrote in 2014, and obviously activists in the global south around the sort of excluded margins have been criticizing Gates, but as far as mainstream, quote-unquote mainstream American media, he went without any criticism up until The New York Times found out that he was hanging out multiple times with Jeffrey Epstein and then the kind of facade, the veneer fell off, and we think that that’s similar to the kind of NGO-Bono-Gates quote-unquote “activism” complex, which has gone completely under the radar and largely, again, except for one 2015 Nation profile, has largely avoided criticism, and we really think it needs to be skeptically addressed, because it does suck up so much oxygen with how people view anti-poverty efforts.

Nima: Even when Gates has gotten critical coverage, it really is for him being a creep, not for him running a grantmaking regime across this planet that actually wields a tremendous amount of power, influence, and gets almost no critical media coverage whatsoever.

Adam: So this will be, I think, our fifth Bill Gates-critical episode.

Nima: Yeah.

Adam: We’re not building a series on this over the years, but specifically, this focuses on the charity spectacle, because, you know, we touch on charity-ism a lot, but I’m excited to kind of get into why we’re not just being hardened cynics, that there are opportunity costs here at work, and we need to really think about whether or not the media attention, resources, energy, celebrity clout, is really worth going into these corporate limited hangouts that, again, not only don’t really do much to meaningfully solve poverty, or they’re kind of this charity model, this tokenism model, but they actually in many ways are validating and providing public relations for the very forces that drive poverty.

Nima: And also the idea that these massive multi-band, multi-celebrity, superstar concerts were taken from their models, say, like a Woodstock model, which was about gathering about certain kinds of ideology, possibly about certain issues, anti-war, et cetera, but then really changed into a fundraising mechanism. So not just fundraising for the promoters — money making — but a so-called humanitarian aid benefit. Now, the first ever massive star-studded humanitarian relief benefit was George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh, a two show event held at New York City’s Madison Square Garden on August 1, 1971, 50 years ago. It included not only former Beatles, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, but also Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Leon Russell, Billy Preston and the band Badfinger. In addition to musicians Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan. Attended by a combined 40,000 people over the course of those two shows, the concerts raised a quarter-million dollars in ticket sales, administered for relief efforts by UNICEF. The subsequent album releases and concert film for The Concert for Bangladesh generated $12 million for humanitarian aid over the next decade and a half. By most accounts, The Concert for Bangladesh was wildly successful and set the template for the superstar benefit shows to come.

Now, while The Concert for Bangladesh was the first benefit show, about a decade earlier, one of the first philanthropies or human rights organizations in this vein, the development funding, the humanitarian aid work was really Amnesty International. The organization was founded by British lawyer Peter Benenson in 1961 in response to human rights abuses in Portugal under the right-wing Antonio Salazar regime and began with a campaign called Appeal for Amnesty. Offering a glimpse into the organization’s centrist political undergirdings, Benenson published a letter headlined, “The Forgotten Prisoners” in the Observer, the intro of which was this, quote:

ON BOTH SIDES of the Iron Curtain, thousands of men and women are being held in gaol without trial because their political or religious views differ from those of their Governments. Peter Benenson, a London lawyer, conceived the idea of a world campaign, APPEAL FOR AMNESTY, 1961, to urge Governments to release these people or at least give them a fair trial. The campaign opens to-day, and ‘The Observer’ is glad to offer it a platform.

End quote.

And here’s an excerpt from the letter itself, expressing its purpose, quote:

The campaign, which opens today, is the result of an initiative by a group of lawyers, writers and publishers in London, who share the underlying conviction expressed by Voltaire: ‘I detest your views, but am prepared to die for your right to express them.’ We have set up an office in London to collect information about the names, numbers, and conditions of what we have decided to call ‘Prisoners of Conscience;’ and we define them thus: ‘Any person who is physically restrained (by imprisonment or otherwise) from expressing (in any form of words or symbols) any opinion which he honestly holds and which does not advocate or condone personal violence.’

End quote.

Adam: So what you see was the kind of emerging negative rights, liberal mode of activism that targeted oftentimes communist countries that were seen as being oppressive. Of course, Amnesty International, infamously, as we mentioned on a prior episode, refused to make Nelson Mandela a prisoner of conscience because he would not condemn or renounce violence as a political tactic. So, what you see is this kind of left, liberal left, kind of negative rights-centered mode of celebrity activism. In 1976, Amnesty International, by then a full-fledged NGO, introduced a star-studded fundraiser series called A Poke In the Eye (with a Sharp Stick), staged in London’s West End. The inaugural performance, a live sketch show featuring famous British comedians, was organized by Monty Python’s John Cleese, Amnesty International’s assistant director, Peter Luff, and entertainment industry executive Martin Lewis.

By 1979, the benefit was retitled The Secret Policeman’s Ball. The Guardian credits the Secret Policeman’s Ball with, quote:

chang[ing] the relationship between charity and the entertainment industry, and influence the humanitarian work of stars such as Bob Geldof, Bono, Sting and Bruce Springsteen, as well as fathering Live Aid, the Prince’s Trust concerts and Comic Relief.

So what you have is you have celebrities sort of athletes in that they’re not really filtered for politics like most rich people are. You sort of filter for ideology when you’re an investment banker or real estate developer or royalty, and actors, like athletes, kind of can become rich while still being like nice people or good people with good politics, which is why so many celebrities can fund left-wing causes, obviously, you know, Jane Fonda, Leonard Bernstein funded the Black Panthers, things like that, right? Sort of was very common in the ’60s like radical politics. Obviously, Hollywood in the ’50s and ’60s funded a lot of radical politics, and so what you have is this kind of emerging NGO mode of political activism, some of which is good, and some of which is a little bit dicey.

Nima: The entire premise of the show.

Adam: Well, right, but that’s the thing is the line is not always clear, Amnesty International can do good work, but Amnesty International always also has very kind of specific negative rights politics, and maybe it isn’t necessarily a very thorough analysis of power that you and I would necessarily think is valuable. Fast forward to the 1980s. In 1986, U2’s Bono told Rolling Stone, quote, “I saw The Secret Policeman’s Ball and it became a part of me. It sowed a seed…” Similarly, Sting stated in a BBC interview that he joined Amnesty International after seeing the Ball, adding, quote, “before that I did not know about Amnesty, I did not know about its work, I did not know about torture in the world.” Boomtown Rats lead singer Bob Geldof, along with Ultravox singer Midge Ure, performed for the fundraiser series in 1981, when it was titled The Secret Policeman’s Other Ball. According to Amnesty International, “Geldof credits the Secret Policeman’s Ball series with having inspired his own charity show endeavors,” including Band Aid and Live Aid.

Nima: Oh yeah, and here’s where we get to the stuff that probably most listeners have heard of, or at least seen parodies of at this point, the kind of Bob Geldof-style benefits show. In 1984, three years after his performance for Amnesty International, Bob Geldof watched a BBC news report about Ethiopia. This report has been described as the inspiration for Band Aid, a charity supergroup founded by Geldof and Ure that recorded the historic single, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” Now, members of Band Aid included a murderers’ row of British and Irish pop stars among them, Sting, Boy George, Phil Collins, Wham!, and, of course, Bono.

The song — “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” — paints a picture of Africa, the continent in its entirety — obviously just one place, a magic place called Africa — as a dreary, desolate wasteland where people must be rescued by the largesse of kindly Westerners and their Christian traditions.

Adam: Needless to say the lyrics of the song were a little dicey. I know they technically can’t be orientalist, because Africa is not the Orient, but whatever the analog for that is for Africa, what you see emerging is this politics without politics that really defines this NGO model. This is really when it starts to kind of cement this world with victims, but no victimizers, and in doing so you sort of come up with this essentialist reduction of what Africa is and what its problems are.

Nima: Along with this like very creepy kind of missionary —

Adam: White savior, Christmas mode. So let’s listen to that now.

[Begin “Do They Know It’s Christmas” Clip]

It’s Christmas time, there’s no need to be afraid

At Christmas time, we let in light and we banish shade

And in our world of plenty we can spread a smile of joy

Throw your arms around the world at Christmas time

But say a prayer, Pray for the other ones

At Christmas time it’s hard, but when you’re having fun

There’s a world outside your window

And it’s a world of dread and fear

Where the only water flowing

Is the bitter sting of tears

And the Christmas bells that ring

There are the clanging chimes of doom

Well tonight thank God it’s them instead of you

And there won’t be snow in Africa this Christmas time

The greatest gift they’ll get this year is life

Where nothing ever grows

No rain nor rivers flow

Do they know it’s Christmas time at all?

[End Clip]

Adam: So yeah, the chorus is “Feed the world, do they know it’s Christmas?”

Nima: That is just magic.

Adam: 1984, obviously, different awareness around these things, and again, we don’t to be too cynical in the sense that I think there was a famine at the time in Ethiopia, but one of the trademarks of these charity events — in case we’ve not been fairly clear as to the thesis of our show — is that they’re totally removed from politics, so there’s no sense, Geldof and others who are involved in this project, seemed totally disinterested in the politics of Ethiopia at the time, namely the history of colonialism, the repressive feudal monarchy that created the conditions for the famine, including a major famine in the 1970s, and so Geldof acknowledged suffering without identifying any cause or perpetrator.

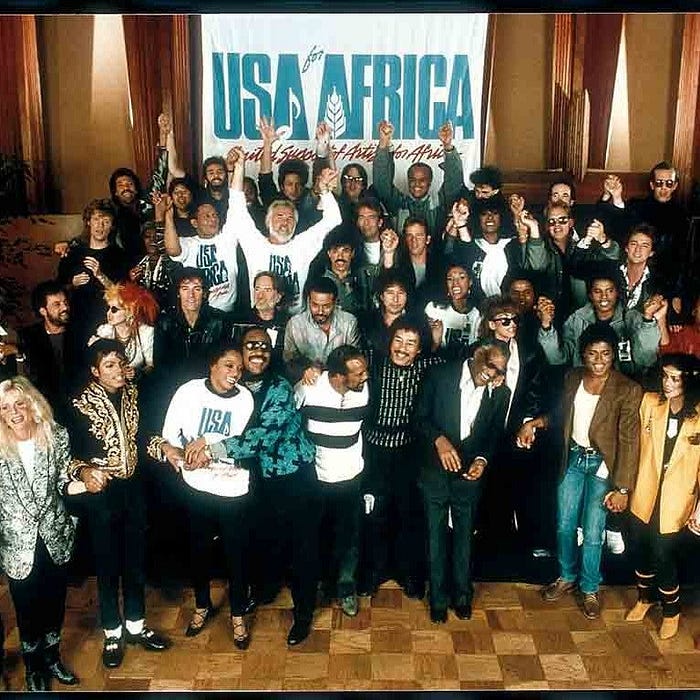

Nima: So this idea of Africa as a country also really gets embedded through this kind of song, of course, you know, 54 countries, 11.7 million square miles, more than 1.2 billion people boil down to a single story, a single kind of sad story, maybe two stories, right? There’s one for North Africa and one for Sub Saharan Africa, this is the Sub Saharan Africa one, just sort of perpetually lingering in the Western imagination is like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, right? Which also has to do with what we’ve talked about on Citations Needed a lot before, and actually with one of our guests, Jason Hickel, this idea of the post World War II, post colonial shift in the Global South, and that a new story was needed for the West, right? A new kind of master narrative to make sense of why the world flush with inequity, look the way it did, which birthed the notion of international development, which actually Harry Truman, in his 1949 inaugural speech, sort of introduced into the political lexicon, the sentimental narrative, Western benevolence, not exploitation or extraction, right? It’s just kind of happenstance, the Global North I guess is just developed somehow and the Global South isn’t, and the plight of poor countries is corruption or poor infrastructure, tribalism or religion, primitive thinking, and that this kind of idea that they live like that over there, and we live like this over here, so we have to then help them. So this idea of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” with its extreme kind of evangelical missionary chorus served also as a springboard for Live Aid, a benefit concert and fundraising campaign. This in turn famously spawned a kind of mini-cottage industry of charity supergroups and their attendant megasongs, foremost among them — my favorite, Adam — USA For Africa’s 1985 hit, just the next year, We Are The World, written by Michael Jackson and Lionel Ritchie, co-produced by Quincy Jones. It features Jackson, Ritchie, Geldof himself, of course, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan, Stevie Wonder, Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Tina Turner, Cyndi Lauper, both Kennys, Rogers and Loggins, Diana Ross, Dionne Warwick, Willie Nelson, Al Jarreau, Journey’s Steve Perry, Hall and Oates, Huey Lewis, Kim Carnes, alongside a celebrity chorus including the rest of the Jacksons, Pointer Sisters, Waylon Jennings, Bette Midler, Sheila E., Smokey Robinson, Harry Belafonte, Lindsey Buckingham.

What was the effect of Live Aid, though? It’s hard to gauge. The BBC in 2010 published an investigative story claiming 95 percent of the $100 million in aid that went to the northern province of Tigray, Ethiopia in 1985, of a total $144 million, had been diverted for military use by the rebel forces in the area. This infuriated Geldof and his “Band Aid trust,” which filed a complaint against the BBC’s reporting, without offering proof to counter these claims. Nevertheless, the BBC retracted the story, namely because of Great Britain’s libel laws, they’re like, ‘That’s not worth it.’ This was an early indication of the inefficacy of “aid” projects, particularly those devised by Western liberal celebrities, without political education and a coherent ideological framework. Decades later, Geldof would become chairman of 8 Miles, a private-equity firm investing in Ethiopian companies, in a move that The Wall Street Journal would call a, quote, “shift from aid to trade,” end quote.

Adam: So here’s Geldof being interviewed by The Wall Street Journal in 2015.

[Begin Clip]

Reporter: So if you, if 8 Miles makes a profit from these investments, you’re making a profit?

Bob Geldof: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, this is capitalism, red in tooth and claw.

Reporter: If you have no idea who Bob Geldof is, he’s the pop star who raised charitable funds for starving people in Ethiopia and now he’s investing in companies in Ethiopia and stands to make a profit. Some people struggle with that.

Bob Geldof: Well, what I do with the profit is my business.

Reporter: Sure.

Bob Geldof: But what the investors do with their profit is entirely their business, and what they will do is reinvest in other companies.

[End Clip]

Adam: Yeah. So again, the framework was always capitalist in nature, and then charity is kind of the thing we use after we get rich when we sort of feel bad about things happening. So this brings us to about the 2000s, where you have the kind of Geldof, Bono, and Bill Gates braintrust gets together. In 2002, Bono and Bill Gates announced at the World Economic Forum their plan to, as CNN put it at the time, quote, “focus the world’s attention on issues confronting Africa.” They called the effort their “DATA agenda,” DATA being an acronym for Debt, AIDS and trade for Africa in exchange for — and here’s the kicker — “democracy, accountability and transparency in Africa.” So again, poverty is a moral failing on the part of Africans. The Gates Foundation was a major donor.

Elaborating on the agenda, Bono stated at a news conference, quote:

It’s a deal, and it’s a tough deal, but we think if we follow that through, by this summer’s G-8 we can get governments to agree on a kind of Marshall Plan for Africa.

Again, what Bono has to do with any of this is never really, you know, he wasn’t elected, he’s not an expert, but anyway:

It’s a good analogy I think, particularly post-September the 11th. … The United States invested in Europe after the Second World War as a bulwark against Sovietism. And it had debt cancellation as part of it, and trade, etc.

At the moment, Africa is in the same kind of vulnerable position that Europe was — to other extremists and ideologies. And I think it would be very smart for the West to invest in preventing the fires rather than putting them out, which is a lot more expensive.

Bono continued to decry corruption in Africa at the time, something he has done countless times since. In 2006, he gave a speech at a conference in Nigeria telling finance ministers of the country that they must strive for, quote, “more transparency, not more bribes.” According to the Irish Times, this occurred just days after the US state department called on Nigeria to make anti-corruption policy a priority.

In 2004, Bono co-founded the ONE Campaign, a Gates-Foundation-funded NGO centered again on, quote, “ending extreme poverty” and preventable disease, especially in Africa. DATA and ONE merged in 2007. ONE now counts among its funders Bank of America, The Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, Cargill — a major contributor to deforestation in Brazil — Coca-Cola, Google, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg.

Around the same time, in 2005, Geldof revived Live Aid as Live 8, another celebrity benefit for Africa, so named because it was held in the mostly Western and Western-aligned G8 summit countries. Geldof reportedly told the manager of an unidentified performer, quote, “Please remember, absolutely no ranting and raving about Bush or Blair and the Iraq war. We want to bring Bush in, not run him away.” Unquote.

Nima: Yeah, this is 2005, remember.

Adam: So again, you have politics without politics. There is some nebulous force causing poverty and to the extent to which it’s named it’s corruption and a lack of transparency. So, around the same time in 2005, 2006, Bill Newcomb, who from 1977 until the time he left Microsoft in 2002, was the head intellectual property lawyer at Microsoft. Around that same time in 2006, he founded the World Justice Project, which is a NGO, that quote, “Works to advance the rule of law around the world.” The World Justice Project created the most famous and most well known Rule of Law Index, where they measure a country’s adherence to rule of law. Now, what does a former IP lawyer, to what extent is he concerned with the rule of law? He is concerned with the enforcement of WTO agreements in the Global South primarily, and uses that as one of their primary criteria, along with some sort of good government liberal criteria that they probably don’t really care as much about, they use that as something they’re very concerned with when it comes to enforcing intellectual property law, which we’ll get into more in just a second.

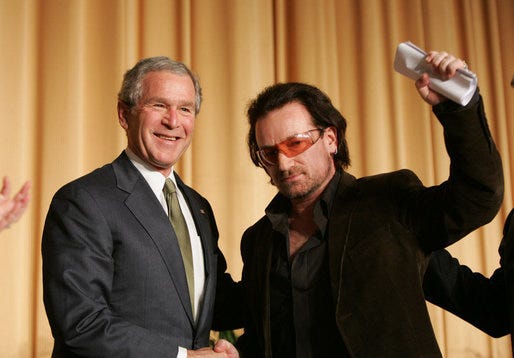

Nima: So what we see through all of these events, all of these benefits is really PR work for American Empire and Bob Geldof and Bono really seem to thrive on this. The same year as Geldof’s Live 8, in 2005, Bono was on Meet the Press and was asked about then US president, George W. Bush, at the time, presiding over a number of criminal occupations in the Middle East, and Bono said this, quote:

I think he’s done an incredible job, his administration, on AIDS. And 250,000 Africans are on antiviral drugs. They literally owe their lives to America. In one year that’s being done. But it can’t just be AIDS. It has to be the environment in which viruses like AIDS thrive, or malaria. I mean, 3,000 Africans die every day of a mosquito bite. Can you think about that, malaria? That’s not acceptable in the 21st century and we can stop it. And water-borne illnesses — dirty water takes another 3,000 lives — children, mothers, sisters.

Yes, there’s a lot of pressure on President Bush. If he, though, in his second term, is as bold in his commitments to Africa as he was in the first term, he indeed deserves a place in history in turning the fate of that continent around.

Adam: So again, you have this kind of benevolent charity model for which only can come from American Empire and corresponding or parallel NGOs and corporations. There’s no other moral vision of activism, the total elite capture of this charity model fronted by celebrities is laundered away at this point, and one thing I want to sort of touch on real quick is we talk a lot about celebrities, and we mostly sort of look at them as sort of good natured, and I think to a large extent that’s true, I do think though, it’s important to understand that people like Bono, international recording artists, actually do have quite an incentive to have strict enforcement of national property, especially around that time, with the, you know, the advent of Napster and other kind of streaming services, that they themselves take, in addition to their charity work, that they sort of buy into this capitalist WTO intellectual property enforcement regime, which kind of leads to our next point about vaccines, which was the impetus of this episode, is something we’ve been criticizing Global Citizen on the show in our own writing for a few months about, which is Global Citizen, as a largely funded by Bill Gates endeavor, is either agnostic to or hostile to efforts from activists in the Global South to undermine what is viewed as the sanctity of this WTO and IMF lead capitalist order. It’s a little weaker now than it was in the 2000s, this sort of before there was a counterweight with China, this was back when it was just basically you had to take an IMF loan or you were fucked. There was literally no other option so you have to put in that context as well, and this kind of speaks to the motive and why Gates pivoted so aggressively to the global health sector. We are going to quote extensively from an article from April of 2021 in The New Republic, which is extremely excellent, you should read, it’s called, “How Bill Gates Impeded Global Access to Covid Vaccines. Through his hallowed foundation, the world’s de facto public health czar has been a stalwart defender of monopoly medicine.” It was written by Alexander Zaitchik, and it really needs to be read in its entirety. We’re gonna read you a fairly long excerpt because I think it sort of sets the table for what the kind of motives are for Bill Gates specifically, without commenting necessarily on others and give some context as to why he was suddenly so concerned with global health and how that dovetailed with his primary avenue of financial investment. You have to understand also around the years 1999, 2000 and 2001 he was the richest person in the world, he was the richest person in the world for well over 10 years, and his foundation, the Gates Foundation, for several years was 10 times greater than the next biggest foundation, the Walton Family Foundation. So this is someone with tremendous power, as we mentioned in our episode on Gates in Africa, this is someone whose personal net worth is greater than 90 percent of the country’s GDP in Africa. So he has tremendous influence over that sector. So we wanted to read this excerpt from that article.

Nima: Yes, and so this excerpt that I’m going to read actually relates also directly to what Bono was saying on Meet the Press, you know, ‘Hey, George W. Bush may have been invading countries and murdering a lot of people but, hey, he really helped out Africa, right?’ So we’re kind of recenter on how the United States dealt with Africa, and especially when Bill Gates was concerned. So this is from the Alexander Zaitchik article in The New Republic, quote:

By 1999, Bill Gates was in his final year as CEO of Microsoft, focused on defending the company he founded from antitrust suits on two continents. As his business reputation suffered high-profile beatings from U.S. and European regulators, he was in the process of moving on to his second act: the formation of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which commenced his unlikely rise to the commanding apex of global public health policy. His debut in that role occurred during the contentious fifty-second General Health Assembly in May 1999. It was the height of the battle to bring generic AIDS drugs to the developing world. The central front was South Africa, where the HIV rate at the time was estimated as high as 22 percent and threatened to decimate an entire generation. In December 1997, the Mandela government passed a law giving the health ministry powers to produce, purchase, and import low-cost drugs, including unbranded versions of combination therapies priced by Western drug companies at $10,000 and more. In response, 39 drug multinationals filed suit against South Africa alleging violations of the country’s constitution and its obligations under the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS. The industry suit was backed by the diplomatic muscle of the Clinton administration, which tasked Al Gore with applying pressure. In his 2012 documentary Fire in the Blood, Dylan Mohan Gray notes it took Washington 40 years to threaten apartheid South Africa with sanctions and less than four to threaten the post-apartheid Mandela government over AIDS drugs. Though South Africa barely registered as a market for the drug companies, the appearance of cheap generics produced in violation of patents anywhere was a threat to monopoly pricing everywhere, according to the drug industry’s version of Cold War “domino theory.” Allowing poor nations to “free ride” on Western science and build parallel drug economies would eventually cause problems closer to home, where the industry spent billions of dollars on a propaganda operation to control the narrative around drug prices and keep the lid on public discontent.

The companies suing Mandela had devised TRIPS as a long-term strategic response to the south-based generics industry that arose in the 1960s. They had come too far to be set back by the needs of a pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. U.S. and industry officials paired old standby arguments about patents driving innovation with claims that Africans posed a public health menace because they couldn’t keep time: Since they could not be relied on to take their medicines on a schedule, giving Africans access to the drugs would allow for the emergence of drug-resistant HIV variants, according to industry and its government and media allies.

In Geneva, the lawsuit was reflected in a battle at the WHO, which was divided along a north-south fault line: on one side, the home countries of the Western drug companies; on the other, a coalition of 134 developing countries (known collectively as the Group of 77, or G77) and a rising ‘third force’ of civil society groups led by Médecins Sans Frontières and Oxfam. The point of conflict was a WHO resolution that called on member states ‘to ensure equitable access to essential drugs; to ensure that public health interests are paramount in pharmaceutical and health policies; [and] to explore and review their options under relevant international agreements, including trade agreements, to safeguard access to essential drugs.’

End quote.

Adam: So the long and short of it is that around 1999–2000, Gates eventually just started donating to Mandela’s charity, donated $10 million to his charity at that point. I think it was headed by his father and he took it over when he left Microsoft later that year. So what they realized what the AIDS crisis in the ’90s, that the biggest threat to the intellectual property regime, which again was central to Gates’ wealth, that’s how we became a multi-billionaire, because Microsoft is infinitely copyable, the only way it works is if you have some kind of global enforcement regime and punishment mechanism, that the biggest threat was public health.

Nima: So the generic Microsoft is illegal.

Adam: Yeah.

Nima: Whereas the Microsoft-Microsoft is the one that everyone has to buy.

Adam: Right, and of course, now most of his money is in Apple, actually, through Warren Buffett.

Nima: Yeah.

Adam: And so what he sort of did when he left Microsoft, around the turn of the century, was, you know, he had made his money, made his billions, that he was going to pivot to public health, I think maybe on some level he thought he was going to do good, maybe, I don’t think he’s a total psycho, but in doing good, he was going to throw his money around the world of public health. Public health was seen as being the greatest threat vertical, if you will, to intellectual property enforcement, because of the obvious moral and emotional sight of watching Africans die when they have $10,000, AIDS drugs, that this was bad for public relations, which the article does a really good job spelling out, and that if he could go in there and basically crowd out the competition, and basically own the sector, through his charity, that he could steer activism and pop public policy and global health policy away from undermining intellectual property regimes, which again, were central to his wealth creation at the time, his billions and billions of dollars, and put it more into this charity model — and where, Nima, have we seen this rear its ugly head over the last two years? — we’ve obviously seen this happen with the COVID vaccines, and this kind of charity model where you prevent the Global South from having political power and agency and the ability to produce generics and the ability to meaningfully negotiate with the Global North by ignoring these arbitrary World Trade Organization patent laws, which of course, themselves were written by Pfizer in the 1980s, you had this charity model where they sort of turned around and they gave table scraps, something one of our guests, Jason Hickel, writes about a lot. So it sort of looks like they’re doing good, and within a sort of, if you accept the premises of the sanctity of IP regimes and global capitalism, it sort of is good in that there’s not really any other option, right? And the holy sanctity of that global capitalist IP enforcement system was not going to be touched by any kind of public health movement, and then of course, you have at the time, you know, you’ve got to understand, two weeks before Bill Gates decided to meet with Nelson Mandela and talk about AIDS in Africa, and he had developed this bad reputation, you know, he was in Seattle at the time during the Battle of Seattle in December of 1999. This was only two weeks after. You have to put it in context, there was this anti-globalization movement, which was still kind of fringe, but had some popular support, you had Global South activists during the South Africa episode in the mid-90s to the late ’90s, you had ACT UP protesting Al Gore for his support of intellectual property enforcement on AIDS drugs, that was obviously bad PR, that he was going to sort of move into this space, and own the space and avoid anything that addressed the fundamental drivers of global poverty, AIDS, and later, of course, climate change, which is now his new big thing, which is a totally separate episode we’ll get into later.

Nima: And what it also does is it merges these ideas of the West being noble and generous with the idea that philanthropic and technocratic solutions are the way that humanitarian relief can be provided, that people are lifted out of poverty and precarity of ill health or government corruption, right? So it bolsters the thing that he already does, it just turns it into , you know, this PR effort, because it’s now in service of humanity instead of his bank account, except his bank account never quite happens to suffer despite all the charity, which then brings us Adam to one of our favorite global charities: Global Citizen.

Adam: So, Global Citizen was created in 2008 as the Global Poverty Project in Melbourne, Australia. Its founder is “humanitarian” Hugh Evans. Prior to Global Citizen, Evans founded the Oaktree Foundation, an Australian NGO that pushes “education reform” in formerly colonized Asian countries. Oaktree now partners with USAID-funded education reform NGOs in places like East Timor.

Evans reportedly founded Global Citizen with $60,000 from the UN and $350,000 from the Australian government. So from day one, Global Citizen was set up not to challenge power, but was funded by powerful institutions. In 2012, Global Citizen had its most publicized event, the Global Citizen Festival. The top donors to the festival, at least the 2018 version, because they’ve done a version of it pretty much every year since then, included Justin Trudeau, Bill and Melinda Gates, and the World Bank. Major sponsors include Cisco, Delta, Live Nation, Citibank, Google, Procter & Gamble, Salesforce. In 2015, as I wrote about for my Substack, Global Citizen did a concert, oftentimes does these kind of controlled opposition stunts with the International Monetary Fund, where there’ll be a World Bank or a G7 or G8 summit that’s sort of in proximity, either geographically or timewise, and they’ll call on world leaders —

Nima: Ah, yes.

Adam: At these rallies to help solve global poverty, they shared the stage in 2015, and some other years, with high ranking IMF officials who give speeches at these rallies to sort of say how they fight poverty. Now of course, the International Monetary Fund, like the World Bank is despised by activists in the Global South, the IMF extorts poor countries with exploitative privatization schemes and structural adjustment programs that drive poverty, which we’ll discuss more with our guests, the IMF is a major driver of poverty and to show how wedded they are to this to this global financial Western capitalist regime as it were, despite all their funders, which should be obvious enough, in 2020, their World Leader of the Year Award went to the EU Commissioner Ursula von der Leyen. The 2018 World Leader Award went to Conservative Party Norway Prime Minister Erna Solberg, both of whom are fierce opponents of the TRIPS waiver, two of the group’s four finalists last year actively work against waiving patent vaccines for vaccines, and the third was the actual head of the IMF. So this is Global Citizen, it is heavily funded by Gates. The concerts it puts on, the Vax Live concerts, which we criticized in our April 2021 News Brief on Global Citizen, are all funded entirely by Bill Gates, you can go look on Bill Gates’ website, it says he gives $1.8 million, $1.5 million, depending on the concert. So Global Citizen is a reputation laundromat for corporations and for Bill Gates and the IMF itself and it is funded by the World Bank. It is funded by the Western banking institutions that help, they are sort of extensively there for global development and relieving poverty, but basically they’re there to enforce structural adjustment programs and the privatization of resources in the Global South.

Nima: To discuss this more, we’re now going to be joined by our first guest, Jason Hickel, economic anthropologist, professor, author, and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. He is Associate Editor of the journal World Development and his most recent book is Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Jason will join us in just a moment. Stay with us.

[Music]

Nima: We now welcome back to the show, Jason Hickel. Jason, welcome back to Citations Needed. It’s great to talk to you again.

Jason Hickel: Hey, it’s good to be here. Thanks for having me.

Adam: So here we are, again, doing an episode that largely focuses on criticizing Bill Gates, but also a kind of broader ideological framework, and specifically this time, there’s a lot that has happened since we last had you on to talk about what you call the sort of development narrative or the kind of Pinker-Gates rah rah development narrative, specifically around the TRIPS waiver issue which we talked about the top of the show, the COVID vaccine patent waiver issue, Gates and organizations funded by Gates have taken heat over the past six months, heretofore unseen, this obviously coincided with revelations that Bill Gates had had multiple meetings with Jeffrey Epstein, which didn’t really help is Teflon PR apparatus. I want to sort of begin by talking about the Gates world’s hardened opposition to the TRIPS waiver, after President Biden in May 5 came out extensively in favor of a TRIPS waiver — although later they dragged their feet to the point where it’s now not really clear if they support it, even in theory — that the Gates Foundation came out and said in this kind of half assed, ‘Oh, we support it, but it has to be narrow,’ but it was more of an ass covering thing. Specifically these kind of high profile concerts with Global Citizen, which focused exclusively on COVAX, much to the suspicion of many Global South activists and anti-vaccine apartheid activists. I want to sort of talk a bit about what, because again, we obviously didn’t talk about this because we didn’t have a time machine at the time, what the Gates world’s opposition, and the heat they got over a patent waiver for COVID vaccine so third world countries could scale up manufacturing, which again, the proposal is a year old now, but they’re still negotiating it — in fact, they’ll still negotiate until at the very least December of this year, so a year and three months after they first proposed it — what does that say about your broader critique of the Gates world, and how does it sort of heighten the tensions and contradictions of their model of charity?

Jason Hickel: Yeah, this is important and fascinating, and to me, it’s amazing, that Gates gets away with sort of portraying himself as this cuddly wise grandfather in wool sweaters who cares about the poor, because the wool sweaters by the way, are clearly a PR tactic, because let’s be honest, he’s a hard nosed capitalist who cares primarily about capital accumulation that has always been for him the bottom line, and his primary strategy for capital accumulation is to lock up intellectual property, create monopolies, and extract rents. So Gates has done more than any other single figure in human history to lobby for tighter IP laws globally, including through the TRIPS agreement, which is sort of in dispute right now, and the collateral damage from this has been extraordinary. So it’s most obvious, of course, in terms of restrictions on access to medicines in the Global South, which is what’s under discussion. Most medicines obviously can be manufactured in generic form for very cheap, but the TRIPS agreement basically makes this illegal to do. So, for instance, a significant chunk of the AIDS crisis can be attributed directly to the TRIPS agreements, which prevented Global South countries from manufacturing and importing generic antiretrovirals for a long time before it was overturned by activist pressure. So it’s an example of how IP law has literally killed people totally needlessly, in large part because of an infrastructure that Gates himself has contributed to building for the sake of his accumulation, and now exactly the same thing is happening with the vaccine. So we have this totally unacceptable apartheid situation where people in the Global North are getting booster shots, while most people in the Global South haven’t even received a single dose, and it’s hard to imagine, to me, a more egregious expression of colonial inequality. So it’s remarkable because basically Gates claims to be a champion of public health, but when the interests of public health conflicts with the interests of capital accumulation, he goes hardcore for the latter, and by the way, I think we should also mention that this is an issue, also, when it comes to renewable energy technology, which no one is really talking about yet. We’re in a situation where we need this technology to be disseminated as quickly as possible to prevent catastrophic climate breakdown, and IP laws are a major obstacle to dissemination. So when it comes to medicines, when it comes to other forms of technology over and over again, it’s clear that capital seeks to enclose key resources that are necessary for survival in order to extract surplus, and that’s basically been the MO of capitalism for 500 years, and it’s extremely dangerous.

Nima: Yeah.

Jason Hickel: So, the idea that the Gates Foundation, Global Citizen, the World Bank, and major capitalist firms and donors, represent an effective force against poverty is just disingenuous in the extreme. The narrative creates the impression that poverty will be solved through the benevolence of the rich. In reality, what is obviously required is a struggle against the forces of capital accumulation and imperial appropriation to win basic principles of social justice, like decent wages, universal public services, and a fair global economy. This is the only thing that has ever delivered effective gains against poverty, but it’s exactly what billionaires are trying to hedge against. So, I think that’s what’s sort of represented in this sort of spectacle.

Adam: But Coca Cola is a major sponsor of Global Citizen. So —

Nima: Yeah, well, exactly. So I guess that makes it okay. I mean, right? So one of the main critiques of this particular episode is the humanitarian benefit concert, the celebrity show. Now, hundreds of years ago, I don’t think the, you know, Medici family was funding humanitarian aid art benefits, and yet we have these high profile fronts now like Global Citizen, that serve the Gates world, to really launder reputations, right? They put on these big concerts, impressive roster of celebrities to say, for instance, combat vaccine apartheid in the Global South, as we’ve been talking about, but suspiciously, organizations like Global Citizen have really nothing to say on patents or trade deals like the TPP or anti-union efforts of large corporations for obvious reasons. They supposedly fight poverty while simultaneously taking money from Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, Google, Cargill, Citibank, Coca Cola, World Bank, who’s who, murderer’s row of Western capitalist interests. Jason, can we talk about the purpose of these big PR spectacles, who they benefit, what their model of, they often kind of coincide these concerts with G8 summits and stuff like that, to call on leaders to step up and be responsible. What is all this really meant to achieve?

Jason Hickel: So the IP regime is obviously problematic to the extent that it restricts access to lifesaving medicines and technology, and I think this much is pretty easy for people to grasp. But it’s also a major mechanism of imperial power in the world economy, and I think this is a point that is worth unpacking a little bit, because it’s a little bit less obvious. So, 97 percent of all patents in the world economy are controlled by firms that are headquartered in the Global North. This represents extraordinary monopoly power that enables them to depress the prices of their suppliers, while setting final prices artificially high, okay? So for instance, Microsoft products and Apple products are produced almost entirely in the Global South, with Southern labor and Southern resources by Southern firms, but Microsoft and Apple control the patents, so they get to dictate the prices, they pay their suppliers, what basically amounts to subsistence wages, and then massively markup the final retail price, which allows them to capture the profits in the Global North and whatever tax haven they happen to use. Okay, so when thousands of Northern firms behave like this, we get a situation where the actual process of production for the world economy happens disproportionately in the Global South, but the income from that production is captured disproportionately in the Global North, it’s not difficult to see that this is a major driver of global inequality, and all of this, in fact, also generates systemic price inequalities between the Global North and Global South, and price inequalities create a problem when it comes to international trade. Okay, so the basic rule of trade is that all imports have to be paid for with exports. So price inequalities mean that for every unit of embodied labor and resources that the South imports from the North, they have to export many more units to pay for it, and this has the effect of generating a massive net flow of embodied labor and resources, labor and resources embodied in traded goods flowing from South to North that’s transferred effectively for free from the poorest parts of the world to the richest, okay? So basically, the patent regime maintains poverty wages in the Global South, perpetuates global inequality, and facilitates a massive net transfer of resources labor from South to North. So, it’s a bit rich that the kingpins of the patent world get away with pretending to care about poverty, when in fact, their method of accumulation does so much to create it in the first place. Social democratic policy was brought in by socialist movements in Scandinavian countries, and this should not be surprising, because under capitalism, obviously, the point of production, the point of the economy is to facilitate the accumulation of capital, not to meet human needs, and so the narrative that’s being promoted here, that capital is how the solution to impoverishment, just gets it wrong on every front, it’s clearly a PR narrative that’s intended to support and get us to buy into this narrative, which maintains our consent for what is a fundamentally unjust system.

Adam: I think, where the contradictions are most stark to me at least, and I think to our listeners who may listen to this and think, ‘Oh, well, you know, Coca Cola and Google, they’re sort of, they’re not good, but they’re sort of benign, or they’re kind of amoral, I don’t really see the problem with them collecting checks from them,’ one of the more, I think, where the rubber really hits the road, where I sort of pause and I think, am I losing my mind? Their relationship and partnership with the International Monetary Funds, something that for quite some time now, the left and even liberals took for granted, was a driver of poverty in the Global South. There was a recent Center for Economic and Policy Research, CEPR, did a report on IMF exploitative loans and effectively blockbuster late fees for these large sums of money they take out. Just two examples, Argentina will spend $3.3 billion on surcharges from 2018 to 2023 alone, Lebanon in 2017, just one other example, used 44 percent of its federal budget just to pay off IMF loans. Now IMF, there’s dozens of these examples, I’m sure you can share several of them, the IMF shared a stage with Global Citizen. One of their top officials in 2015, and they’ve done this a few times, and they talk about how they’re really working to fight global poverty. In 2020, the head of the IMF was a finalist for Global Citizen’s World Leader Award, they have financial ties with and obviously Global Citizen’s funded by the World Bank. I want to sort of talk about this, obviously, things like opposition to structural adjustment programs, these extortion loans, these surcharges, which again, if one can read the CEPR report, it’s a little dry, but it’s very interesting because these are basically just tacked on late charges, for lack of a better term, they have no value at all. I want to talk about how we hold up these major drivers of poverty in the Global South, again, something I think was pretty much conventional wisdom like 10 years ago, they’re held up by Global Citizen, not only as not causing poverty, but they’re actually actively seeking to stop it. I want to talk about the Global Citizen’s cozy relationship with the IMF, and what that says about this broader narrative.

Jason Hickel: Yeah, it’s interesting. I mean, okay, so the IMF loans are problematic for several reasons. The most obvious, of course, to most people is the fact that this is basically an extortion at debt relationship, as you pointed out, so you have countries like Lebanon who spend a huge chunk of their national budgets basically servicing interest payments to Western banks, right? And sometimes these loans have been paid off many times over, they are old. But the bigger issue here is that the IMF structural investment programs basically prevent Global South countries from using the policies that we know to be effective when it comes to reducing poverty and improving development outcomes, and this is really where the rubber hits the road and it’s terrible, because Global Citizen is promoting this narrative as part of a kind of development and poverty reduction narrative. But, in fact, the IMF does the opposite, and this is clear when we look at the history of the past couple of decades, because we know that in the immediate postcolonial decades, you know, the ’60s and ’70s basically, independent governments were rolling out progressive, in many cases socialist economic policies that were designed to delink the South from imperial exploitation, and build sovereign economic capacity using things like tariffs, subsidies, capital controls, nationalization of key resources, land reform, labor unions, social spending on healthcare and education, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, and it was working remarkably well, and it was extremely successful in reducing poverty. But the problem with this approach was that it cut off the North’s access to the cheap labor and raw materials that Northern capitalism fundamentally relies on, and it led to a crisis of capital accumulation in the Global North, and to solve this crisis, the IMF was basically sent out to impose structural investment programs across the Global South which reversed these progressive reforms, pretty much in one fell swoop with, you know, enforced liberalization, privatization, austerity, it led to an incredible increase in impoverishments and in hunger, and triggered these riotous protests against the IMF across the Global South, and it’s amazing now that the reputation of this institution is being laundered like this so explicitly, and I guess the people don’t have enough historical memory to sort of recall the points that were established by the anti-globalization movements against the IMF.

Adam: Yeah, because they’re also heavily funded by the World Bank. Can you talk for a second about the World Bank and how it sort of functions in this broader development narrative? Because unlike the IMF, they actually get direct funding from the World Bank, and quite a bit of it actually.

Jason Hickel: Yes, the World Bank is funny because, in some ways it’s kind of worse than the IMF, because it sort of brands itself as this institution that’s organized around ending poverty, right? Like that is it’s explicit —

Adam: Right.

Jason Hickel: Okay. So the IMF is explicitly about economic stability, and in fact, induces instability, and the World Bank is explicitly about ending poverty, but in fact, produces poverty. So it’s one of those bizarre Orwellian nightmares that we’re in. So, I mean, look, the two are sort of twin institutions and the key thing to understand is that in both of these institutions, the G8, and specifically the USA, controls the decision making. So the G7 has more than 50 percent of the votes in both of these institutions, and the USA has veto power over all major decisions, which is crazy, given the fact that these are the key institutions of global economic governance, that the Global South, which has a majority of the world’s population, would have a minority share of votes in these institutions. I mean, if that was the case in any national governments, we would clearly recognize this as apartheid.

Adam: Have you heard of the US Senate?

Jason Hickel: It has obvious racial dimensions and yet this form of apartheid operates at the very center of global economic governance, and nobody really bats an eyelid about this. It’s very bizarre.

Nima: Yeah, it really makes you understand what “world” in World Bank or “international” in International Monetary Fund really means, and it doesn’t mean the world, right? “We Are the World” actually takes out a much starker context, when you realize that, you know, it’s an American celebrity singing that. So, you know, another thing that we’ve been focusing on in this episode is how these kinds of big spectacles not only do the reputation laundering that we’ve been talking about, but also how they really steal the attention, deliberately so, away from protest movements. So, you know, Jason, you were just talking about the anti-globalization movements, you know, think about 20 years ago, 20 plus years ago, so much media attention on, say, protests happening at a global summit, or certainly, you know, WTO meeting, that the media would actually cover that as a spectacle, right? As an activist spectacle on purpose designed by protesters and activists and advocates to do that very thing, to get the attention of the media. It seems like these now, kind of big celebrity events, put on by those very institutions that are the targets of anti-globalization protests, now become not only fodder for media attention, but it’s almost like, they’re almost branded as protests themselves, right? Because they’re the ones getting out there. ‘We are all in solidarity and we’re calling on the leaders to do something, you need to do this, you need to pay more attention to this.’ But then it’s like, sponsored by Bank of America and Google, right? And so can we talk just a little bit about how not only the kind of limits and problems of the Bill Gates-Bono activist model, but also what it’s doing to really train media attention away from where it used to be, and put it to where it can just kind of like, seed the status quo further.

Jason Hickel: Yeah, no, no, it’s amazing actually, and yeah, I mean, the story of the anti-globalization movement in terms of media coverage is crazy, because, as you pointed out, at one point, it was grabbing headlines, and now it’s nowhere to be seen — and yeah, that’s a disaster. But look, I think the bigger issue here in some ways, is actually like, yes, the anti-globalization movements that we saw, sort of represented in Seattle, et cetera, et cetera, that was clearly an important progressive force, but a significantly more important progressive force throughout the history of the past several decades or past century, has been the anti-colonial movements from the Global South with allies in sort of particular segments of the Global North. So when it comes to questions of poverty and development, et cetera, et cetera, again, the only effective force against the scourge has been the anti-imperialist movements, and today it’s alive and well and is clearly represented in a vast range of social movements in the Global South. Take, for example, read the People’s Agreement of Cochabamba, okay, so signed in 2010. It’s a document about the climate crisis, and it’s by far, in my mind, the most important document on this issue ever written. It was signed by thousands of social movements across the Global South, and it’s explicitly anti-imperialist, explicitly, it’s clear that among social movements in the South, their analysis of our crisis-ridden system, everything from inequality to mass impoverishment to climate and ecological breakdown, recognizes imperialism as the core problem here, and yet, that’s not part of Western discourse, and is barely part of progressive discourse even, and that’s a problem, I think. But fortunately, I think that it is increasingly emerging as part of our discourse. But again, it’s being brought by indigenous movements in the Global North as well as social movements in the Global South, not just the People’s Agreement, but look at like the Red Deal published recently by indigenous activists in North America, or the Managua Declaration published by La Via Campesina, the network of sort of anti-imperialist peasant farmers around the world, the Anchorage Declaration, the People’s Vaccine campaign actually is kind of an example in my mind of the anti-imperialist movements coalescing around this issue. These are clearly the progressive forces in history and in our world today, not the World Bank and the IMF and Global Citizen, and so it’s essential that we shine the spotlight on these movements, which have always existed in some form and recognize that our future lies with them. Our future lies with these movements succeeding and we need to line up with them in solidarity.

Nima: Yeah, it’s pretty remarkable that, you know, exactly a decade ago, Occupy Wall Street was in Zuccotti Park and now during a global pandemic, we have Global Citizen in Central Park in New York and it’s like, oh, okay, what a decade it’s been.

Adam: Yeah, I mean, it’s the thing that I find kind of bleak about this is that a lot of people fall for it and then when you sort of point out that maybe we shouldn’t rely on the forces driving poverty to sort of prop themselves up as anti-poverty, so many celebrities we have Coldplay, BTS, Bono, Selena Gomez, I mean name it, I mean Jimmy Kimmel, even sort of your sort of good-natured who don’t sort of know, they don’t really sort of know better because it’s they suck up all the oxygen, and again, I’m maybe I’m a little bit too paranoid, but I really do think this to a large extent, the goal is to kind of take these high profile activists and channel them into this bullshit because again, they were raising money for COVAX, and they actually had a program where you could text to like T-Mobile or AT&T to donate $1 to COVAX and Bill Gates cut a promo for them and I’m sitting there just, I’m like Bill Gates could fund COVAX tomorrow in five minutes. The problem with COVAX was never the lack of funding, it was the fact that none of these so-called pledges from the Global North for vaccines were at all enforceable, I mean, the European Union pledged 200 million doses in December of 2020. As of August of 2021, they had delivered less than 7 percent of those doses then literally like the next day, they pledged 200 million doses again, and they made all these headlines. Meanwhile, the EU is the biggest single, European Union Commission, is the single biggest barrier to a TRIPS waiver, even more than United States, which is batshit, because the United States is the United States and we’re, you know, we’re usually the most, but the European Union is the one holding us up, and so you see the head of the European Union Commission being praised by Global Citizen as this anti-poverty hero and being nominated for a world leader of the year and I just, again, you feel like you’re, you know, the word gaslit gets thrown around a lot, but I think it seems like an apt term. So, I guess what would want to ask you, Jason, is, and this is kind of maybe a little bit of a goofy question, but I’m curious to hear your answer, which is, if there was a kind of good-natured celebrity listening now who sort of wanted to do good, what would you tell them? Would you tell them to sort of maybe avoid this claptrap and what organizations maybe we should be highlighting, and I know you already named a few, but what would you say to them?

Jason Hickel: Yeah, I mean, okay, let me just first think about this a little bit, because COVAX is an interesting phenomenon, right? I mean, for me, initially, it also sounded like a good idea, but it’s very clearly either been intentionally designed to be or is being used as a distraction mechanism from the ultimate objective, which is to decommodify the vaccine.

Adam: That’s right.

Jason Hickel: And it’s wild when you think about it, because it’s true, you know, these pledges are unenforceable, totally non-binding, but also the pledges, even on their own terms, are utterly inadequate. I mean, 200 million doses? Give me a break. That’s a fraction of the global population. It’s child’s play. It would barely vaccinate a country much less, you know, the billions of people who have yet to receive access to a vaccine. So, yeah, I mean, it’s obviously a clear example of the charity model in action, which is basically let us maintain a system that’s organized around appropriation, and then give you some leftovers as a salve, and that’s literally, when it comes to COVAX, that’s literally what’s going on. I mean, these are literally the leftovers of Global North vaccine consumption, and, I mean, it’s insulting in the extreme, and the fact that this is not recognized in Western media discourse, is indicative of how little Western media pays attention to perspectives from the Global South, where it’s widely recognized that this is obscene, a travesty of human rights and just a slap in the face.

Adam: It’s also just extremely inefficient, like the idea that you would sort of cook a meal, you know, bake it in the oven for 30 minutes, then give your table scraps as opposed to giving someone —

Nima: The recipe?

Adam: Millions of people the ability to make the food themselves, on its face it doesn’t make any sense.

Jason Hickel: Yeah, I mean, again, the entire product is clearly intended to prop up the existing IP model and protect it from dissents, and it’s worked so well, right? I mean, the fact that it’s such an obvious campaign to get behind, the People’s Vaccine campaign, but COVAX has just pulled so much of the oxygen out of that movement, because again, celebrities are just like, ‘Oh, this sounds like a great plan. It’s a multilateral cause let’s get behind that.’ And I’m sure that they’re well meaning, but it’s a total trap. It’s a distraction. And, to me, the main problem here with people like Kimmel, there’s just a fundamental lack of analysis. People don’t understand how the world economy works, that traditionally the left and unions have been the vector of sort of education or sort of transmission of this kind of knowledge to understand how capitalism actually operates, how it causes poverty elsewhere, et cetera, et cetera, but in the absence of an effective labor movement, and in the absence of like a radical progressive movement in the Global North, which is sadly the case right now, and in the absence of an effective anti-imperialist alliance, then we have the sort of complete failure of political imagination, and the result is people like Jimmy Kimmel, right? Who sort of parade this absurd charity model as if it’s serious, and it’s totally unacceptable.

Adam: Yeah, I mean, it’s also the incredible sophistication of the NGO complex, which is a whole different episode, but you look at some of these websites that are Gates funded, and it’s like, it’s so hard to do sort of even tell even for a cynical media critic who does this for a living, it’s hard to tell sort of what are, you know, sort of well oriented and not sinister NGOs and which aren’t because it’s not always clear and obviously there’s sometimes a mix of both. I mean, anyone in this world knows that it’s not always going to clear cut and that’s what made the TRIPS waiver debate so interesting to me, because it was so egregious and so obviously calculated that mainline liberal groups that are not necessarily even left or anti-imperialist, like Human Rights Watch, and Doctors Without Borders were like, ‘Well, this is obviously a no brainer,’ and so you had this kind of breakdown of the NGO industrial complex where the odd man out, the total people looking from the outside in was Gates world. I mean, that was it. There was no one else. If you got funded by Gates, you were either quiet or an opposition subtly in opposition to the TRIPS waiver, and if you were not, you were for it, and it was wild to watch because it was the most predictive metric. If you saw someone published an op-ed in the Washington Post that was like ‘Well, maybe you know, the TRIPS waiver is a distraction, it’s really about technology transfer and COVAX,’ and then if you looked it up, like there was a 99.99 percent chance they were funded by the Gates Foundation, and now it was one of the more it was, it was interesting because it basically, again, I think, not to blow smoke up your ass, but I think it vindicated most of your criticisms that we had made before about that whole world.

Jason Hickel: Yeah, yeah, no, it’s troubling indeed, and look, I think when it comes to alternatives that people can get behind. I think it’s just obvious, rally behind the People’s Vaccine campaign, and any organizations that are promoting that are worth supporting for that reason. But I think we also have to push this horizon a little bit, right? And we should take the opportunity to do so. The broader principle here has to be not just patent waivers on the vaccine, but patent waivers on everything that is necessary for all medicines and technologies that are necessary for human survival and well-being, particularly in an era of ecological breakdown. So, we need to push the principle of de enclosure to the extent that capitalism has always relied on processes of enclosure, our position has to be to constantly push for the de enclosure of the commons, these should be commons, and that’s the broader principle we have to push for.

Nima: So I think that’s a great way to get into my final question here, Jason, which is your latest book is Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, you’re now talking about de enclosure, what’s the next “de” we can look for from you, what are you working on these days, and how can people get involved?

Jason Hickel: Yeah, so I’m working a little bit more these days on imperialism, and we have a couple of papers coming out that illustrate our findings on this empirically, which is to me pretty exciting. I don’t know how geeky people get about imperialism, but —

Nima: We are all about geeky anti-imperialism here on Citations Needed.

Jason Hickel: I’m thinking more about the extent to which imperialism is deeply related to the ecological crisis, so that’s what I’m focusing on now, and I’ll be posting papers in the coming months.

Adam: Well, when we do our episode on Bill Gates’ pivot to climate change over the last six months, which I’m sure is going to be 10 times more curse than his mysterious pivot to global health in 1999 to 2000, we’ll be sure to have you back on to talk about all the ways in which he has made sure that whatever we do, we do not undermine the extractivist model. So, very exciting times.

Nima: Yeah, exactly. So look out for that. Jason, you’ll be hearing from us again for sure. I think that’s a great place to leave it. We, of course, have been speaking with friend of the show, Jason Hickel, economic anthropologist, professor, author, and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. He is Associate Editor of the journal World Development and as we have been saying, his most recent book is Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, published last year by Penguin. Jason, as always, thank you so much for joining us on Citations Needed.

Jason Hickel: My pleasure. It was good to be with you guys.

[Music]

Adam: Yeah, I think what Jason does really well, which is why we keep inviting back onto the show, is he sort of shows the connective tissue behind the broader systems at work, so we’re not just giving a bunch of lefty dogmas.

Nima: So we don’t just make broad ideological demagoguing assertions.

Adam: Yeah, about like, you know, rapacious, imperialist, capitalists, because again, at some point, these slogans, I think that jargon at some point kind of loses its purchase and becomes a little bit sloganeering, and I think what Jason’s work does really well, especially The Divide, which if you haven’t read it, please, please, please read it, it really does kind of, it provides kind of motive, Global Citizen and Bill Gates, they’re not sitting around twiddling their moustache, the ideology flows from their financial interest in the power structure, because again, if I’m on top, by definition, I believe I ought to stay on top, and that the system that made me wealthy, which again, and Bill Gates this case was quite literally intellectual property enforcement, right? Otherwise, there’s no such thing as Windows because it’s easily duplicatable. It’s easily stealable, as anyone who lived through the torrent days of the early 2000s knows, that naturally that’s the system that is the only ticket in town, everything else is a pie-in-the-sky, far-left fantasy. So within that narrow ideological framework, they may have developed the most moral system possible, but you’re granting an ideological framework, which is not, despite what they believe, a law of nature, it is manufactured politically, and so this quote-unquote “activist model” where we have these sort of capitalist pep rallies in Central Park, and then we sort of ask for table scraps with all the aesthetics of leftism, all the sort of aesthetics of protest, the aesthetics of —

Nima: Of calls to action and popular collective protest, gathering, unity, right?

Adam: Yeah, and something seems off when you’re sharing a stage with the CEO of Procter & Gamble and IMF, it’s like some alarm bells have to go off. It’s sort of like when I used to go to those creepy Christian meetups that your buddy would take you to in high school when he was trying to convert you and you’d show up and then everything was really positive and, ‘No it’s not about church, it’s just rock and roll,’ and you’re like, now there’s something else going on here, this is not right. It has that vibe, the sort of creepy, again, Gates directly funds these kinds of creepy rah rah concerts for COVAX and I think Jason does a great job showing why that is, sort of what their real purpose is.

Nima: I like making that connection between Global Citizen and the end scene of God Is Not Dead, (laughing) the big concert. It’s all this big kind of creepy evangelical shit, right? And so one is religious, and one I mean, which is also the evangelical one is also colonial, obviously, it’s kind of a missionary idea, this evangelical capitalism, evangelical imperialism.

Adam: Well, it’s when you pivot from protest to pep rally, right? You’re not opposing something, you’re cheering on this very vague concept, and then we’re, you know, again, there’s just going to be a separate episode, but where it starts to dip its toe into climate, I really think you get into even more sinister territory, but again, we’ll do that at a later date, because that’s now where all this kind of energy is going, this very vague climate activism where you basically text your legislator.

Nima: Yeah, exactly. But to talk more about this, we’re going to be joined by our second guest today, Jaume Vidal, Senior Policy Advisor at Health Action International. Working at the intersection of intellectual property rights, access to health technologies and human rights, he leads HAI’s European advocacy on innovation, transparency and trade. Jaume will join us in just a moment. Stay with us.

[Music]

Nima: We are joined now by Jaume Vidal. Jaume, thank you so much for joining us today on Citations Needed.

Jaume Vidal: Thank you for having me.