Episode 130: ‘Heartland,’ ‘Middle America,’ and US Media’s Vaguely Nostalgic, Racialized Code for White Grievance

Citations Needed | February 3, 2021 | Transcript

[Music]

Intro: This is Citations Needed with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson.

Nima Shirazi: Welcome to Citations Needed a podcast on the media, power, PR and the history of bullshit. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam Johnson: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: Thank you everyone for listening. Of course you can follow the show on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed and become a supporter of our work through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson. All your help through Patreon is always incredibly appreciated, it keeps the show independent, it allows us to produce our full length episodes and give you some News Briefs along the way.

Adam: As always, you can rate and subscribe to us on Apple Podcast, that is very much appreciated.

Nima: “We need a president whose vision was shaped by the American Heartland rather than the ineffective Washington politics,” declared presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg. “AOC Kills Jobs Middle America Would Love to Have,” proclaims The Washington Examiner. Amy Klobuchar insists she’s a “voice from the heartland,” while The Washington Post’s Jennifer Rubin tells us, “[Bernie Sanders] is not going to sell in Middle America. You have to WIN Middle America.” Everywhere we turn in American political discourse, the terms “Heartland” and “Middle America” are thrown around as shorthand for quote-unquote “everyday” men and women somewhere between the Atlantic Ocean to the East, Pacific to the West, Canada to the North and Mexico to the South, those people who are supposedly insufficiently represented in media and DC circles. Those evoking their status presumably are interjecting these true Americans otherwise overlooked needs into the conversation.

Adam: But terms like “Heartland” and “Middle America” are not benign or organic terms that emerged from the natural course of sociological explanation, they are deliberate political PR products of the late 1960s emerging in parallel with a shift from explicit racism into coded racism. Their primary function is not to discuss the political will of a vague, non racialized cohort of people situated in the midwest or the “middle” of the geographic United States, or even white people as such, it’s to express a deference to and centering of whiteness as a post-civil rights political project.

Nima: Indeed, the use of “Heartland” and “Middle America” in a non-agricultural context among the pundits, politicians and the press was largely nonexistent until the presidential campaign of Richard Nixon in 1968 and its use, from the outset, was exploited to describe — without offending these very same white people — those opposed to the gains of civil rights, school integration and welfare programs benefiting black communities. The rise of these terms in popular discourse parallels exactly the rise of white flight, Richard Nixon’s so-called “silent majority”, school bussing and the broader political project of the American suburbs.

Adam: On today’s episode, we will explore the origins of the terms “Middle America” and “Heartland”, what they mask, what they reveal, why they’re still used today, and how conversations about “whiteness” as a political ideology would benefit greatly from being clear that this is the subject being discussed, rather than relying on code words that vaguely allude to the subject of political “whiteness” without clearly stating it.

Nima: Later on the show we will be joined by Kristin Hoganson, Professor of History at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She is the author of books including Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920; American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century; and Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. Her latest book, published in 2019, The Heartland: An American History.

[Begin Clip]

Kristin Hoganson: I think in those narratives what gets lost is that the United States has exercised tremendous global power, right? That the history of the United States in the 20th century world is not just one of victimization, but it’s a story of a superpower that has really profoundly impacted the lives and well-being of people in other countries and I think the heartland myth is at the base of those claims, because I think a key component of it is that there is an isolated core at the center of the country that is this buffered place that has been protected from the rest of the world, that the people there are profoundly isolationists in opposition to coastal elites, who are the capitalist class, who have investments and financial commitments to other parts of the world, and that real America is inward looking and cut off from the rest of the world.

[End Clip]

Adam: The terms “Middle America” and “Heartland” are used so often we sort of barely even notice.

[Begin Clip Montage]

Dennis Kneale: I am fresh from the heartland, we’re ready to go.

Ed Schultz: This is outside the Beltway. This is outside the Big Apple. This is out there in the Heartland, in Indiana and Colorado. This is a grassroots effort.

Pete Buttigieg: I also think it helps if we produce a nominee from the Heartland.

Jon Scott: From Guantanamo Bay to America’s Heartland, the White House today announcing this will be the new home for nearly 100 detainees who are now at Guantanamo Bay. It’s a state prison in rural Illinois.

Ann Curry: The veteran newsman reports from the Heartland of America.

Kayleigh McEnany: Here in New York City, deeply out of touch with Middle America.

Laura Ingraham: The primary reason that Trump ran for office was so he could fight for American workers, especially in the factory towns across Middle America.

Bernie Goldberg: Elites, whether they’re in the media or not, look down their long elitist noses at people in middle America, they think Middle America is a barren desert.

Michael Smerconish: We may be watching the start of a populist movement on the left, but what is it? And what does Middle America think about it?

Pat Buchanan: It’s the base of the party and it’s also the base of Middle America, sees losing a country because they got an invasion.

Joe Trimbell: That’s Alameda for you. It’s like a little piece of Middle America here in the Bay Area.

Tucker Carlson: What’s so striking is that Middle America, the parts of the country that have been most wounded by these changes, the economic changes the country’s gone through, are Republican areas, mostly.

Ainsley Earhardt: Your administration’s base is in Middle America.

Pete Buttigieg: These Heartland values don’t have to lead you into the arms of the Republican Party, especially this Republican Party.

[End Clip Montage]

Nima: The words “Heartland” and “Middle America” succeed as political propaganda terms, because they both cleverly sneak in normative value claims under the guise of value neutral descriptors. “Heartland” ostensibly refers to the heart of the country, the thing in the middle, from its earliest reference, indeed, from the term’s invention, “heartland” was used in an imperial and in fact a distinctly anti-Russian context. In his 1904 analysis of geopolitical strategy entitled The Geographical Pivot of History, English geographer Sir Halford John Mackinder coined the phrase to mean the central Eurasian landmass, the strategic center of industry, farming and energy and specifically the part of the world that then comprised the Russian Empire and just a decade and a half later, the Soviet Union. Mackinder later wrote in 1919, after the First World War, that:

“Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland;

who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island;

who rules the World-Island commands the world.”

This would later be known as the Heartland Theory, the academic underpinning to imperial and colonial geostrategy. In effect, the scholarly mirror of the board game Risk.

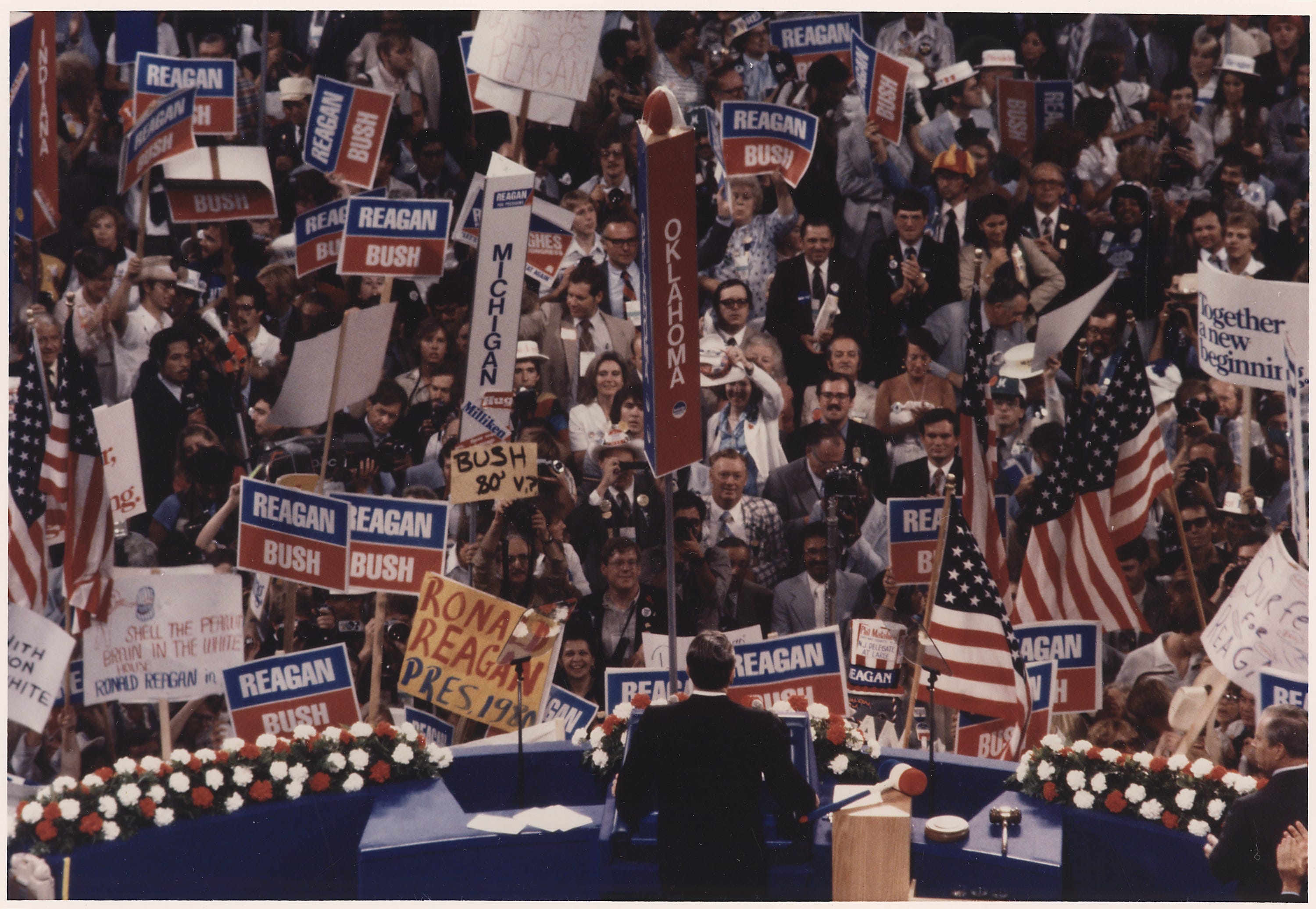

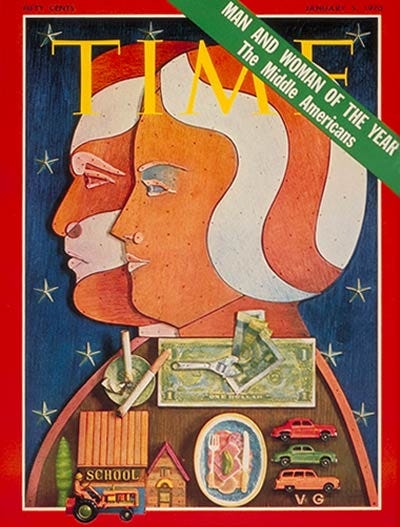

Adam: It’s second and more modern usage that we’re using today really emerged in the early and mid-1960s and peaked in the late-1960s, early ‘70s. Not just to speak to an agricultural center of the United States, but a moral center of the United States and unpretentious average baseline of kind of yeoman, white farmer types as political shorthand for white identity politics, specifically white identity politics in rural America or illiberal cities. The second term we’ll discuss is “Middle America,” which was cemented in popular consciousness around the same time, a little later, New York Times and other newspapers started using “heartland” around 1962, 1963 and almost always in reference to the social unrest and changes that were happening at the time. So “heartland,” from its beginning, was a phrase used to discuss those that were reacting to the social changes, the anti-war movement, the Black Civil Rights Movement, Women’s Liberation Movement. So from the get go, it was by its very nature, a reactionary term. The term “Middle America” was coined in 1968 by syndicated columnist Joseph Kraft, and it really reached its peak popularity in 1969, when TIME Magazine declared 1969’s Person of the Year, “The Middle American,” and this was, solely in relation to those who reject what TIME Magazine refers to as the excesses of the late-1960s. Once again, like the term “heartland,” which smuggles in a normative claim about having a heart or a moral center, “Middle America,” recast reactionary right-wing politics is being in fact middle ground, in time and again, and we’ll read from the TIME Magazine Person of the Year article a bit later, but they are references, they’re not George Wallacites, they’re not the far-right, they’re not overt segregationist. Therefore, because of the existence of George Wallace, the Nixon base, and Nixon himself, is presented as Middle America, in relation to the radical left-wing. Middle America is presented as being exclusively white and middle of course, has normative connotations. Middle is good, right? It sort of connotes moderation, both in terms of, it’s not just a geographic term, the sleight of hand is really done because it says their politics are in the middle. This is Middle America, the suburbs, they’re average, right? All of this has sort of normative baggage, which recasts Nixon-era white reaction to the civil rights movement and anti-war movement as being the center, the thing that’s rational and in the middle of the country.

Nima: That centering also moves away from the coasts, teeming with immigrants and Blacks and Jews, right? The middle of the country is this white centrality at its core, both in values and also race. Now, the reality of this, the history of this is false, it is a myth, but that is how it is using these double meanings of both geography and values were almost certainly not by initial design, yet it’s the reason that they grew so popular and have since never really gone away. Their primary evolutionary advantage, these terms, why they survived when other 1960s-era code words kind of failed to do so in the same way or fail to still have that same kind of cachet as they have now, is inherent in their value the way that they are loaded code words that associate whiteness with a default Americanism, a reaction to both right-wing and left-wing perceived extremism, a connection with the center and the politics of rural or suburban America as necessarily more American than other things.

Adam: Using Ngram and a Newspapers.com search one sees that the term “Heartland” reached its peak popularity actually in 2004 during the post-9/11 Bush years. This obviously paralleled the rise of “homeland,” which is sort of similar, has similar connotations, but it really took off as a political ideal in the late 1960s, along with middle America. Newspapers.com, The New York Times and Google’s Ngram shows a similar peak with the word “Middle America” which reached its first peak in the early 1970s and then was later brought back again and peaked in 2004 during the Bush years. So we had this kind of soul searching for some generic middle of whiteness that needed to be appealed to in the first instance of “heartland” as a kind of political project was found in The New York Times in 1962. This was about six years before the term “Middle America,” its cousin, was coined. The article reads, from June 1962, “Report from the American ‘Heartland’: Not so overwhelmingly agricultural as the cliche suggests, the Middle West represents in an important sense the ‘true’ America, a balance wheel for the nation.” Middle America, actually, prior to 1968, fun fact, usually meant Central America, that’s what you’d refer to as Nicaragua, Panama, Costa Rica, etcetera, you refer to that as “Middle America.” That is obviously no longer the case. This article, somewhat detachedly, but I think somewhat sincerely, presents the idea that the middle of the country, the heartland, is marked by certain values and we see this time and again, this kind of uncritical assumption that they’re kind of morally superior to everybody else. The heartland has a reputation of being the:

“…‘true’ America, embodying its ideals, its sturdiness of character and its homespun sagacity about world affairs — in an unstable world, a rock of tradition and a bulwark of truth to cling to.

“‘The president ought to come out here and talk to some farmers,’ a visitor said the other day. ‘He’d get better advice than he’s getting from those college professors and experts.’”

So, from the beginning, this concept of “heartland” is also tethered to anti-intellectualism and the article would go on to sort of hand wring about the sort of social changes that are happening and how those have not yet reached the heartland.

Nima: Another example of how columnists avoided discussing whiteness as its own political ideology or political current was an editorial from a number of years later, this from September 1969, during the Nixon administration, from the Lexington Leader and in it it says this:

“As a result of this trend, the Heartland — the land of Methodist church suppers, mile-high mining camps, county fairs, steamboats round the bend, cattle drives, waving wheat, Park Forest, Middletown, German biergartens, Polish polka parties and elm lined Main Streets, U.S.A. — is shaping up as the mainstay of a new political era. To define the Heartland with more geographic than sociopolitical precision, it includes every state without a coastline or seaport, save Vermont, and reaches from the Appalachians to the Rocky Mountains. Together, these 25 states cast 223 of the 270 electoral votes needed to elect a President of the United States. In 1968, Nixon carried 21 of the 25 Heartland states. Kindred areas like the Outer South and Southern California (heavily settled from the Heartland), provided the additional margin of victory.

“There can be little doubt of the effect that the Negro revolution has had on the Heartland. The old division — the alignment of the Southern oriented Border and Southwest against the Northern settled Great Lakes, Farm states and Northern Rockies — is no longer valid. The Heartland is no longer just a spatial concept; it is becoming an ideological entity. Within the House of Representatives, most votes on Great Society issues have straddled the old Civil War division, joining the South, the Farm Belt, the Rocky Mountains, the border and the Great Lakes against the Pacific, the Middle Atlantic and New England. The old Blue-Gray ‘Border’ is the border no longer. A new ideological fall line is emerging in the Great Lakes and along the Pacific; its basis is sociology, not history.”

Adam: Yeah, so from the beginning, they say, ‘Oh, it’s a geographical space, but it’s not really,’ it’s a moral idea or a political project, and again, all these things are talking about the preservation and protection of whiteness, because the lumping of white flight from the urban areas to the suburbs and kind of merging with the rural areas, is clearly what’s being talked about in Nixon’s popularity, you know, law and order, peace with honor, all these kind of very white centered ideas are not really given any kind of credence. And so, in 1969, The New York Times ran an article that kind of said as much, their headline was, “Change in the Heartland” and they went to Stevens Point, Wisconsin, and did similar hand-wringing, and using obviously sort of more dog-whistles than one can count.

“Stevens Point, Wis., Oct. 28 — A man looking for the old America, the mythical American where life was not complicated by problems of cities and race and change generally, might have tried this town among the rivers and irrigated farms of central Wisconsin. It seems a Sinclair Lewis town, clean and well-ordered, population 20,000 with no buildings more than a few stories high and hardly a black face in sight.

“To Stevens Point yesterday came 250 juniors and seniors from the high schools of Wisconsin’s Seventh Congressional District, the one Melvin Laird used to represent before he became Secretary of Defense. They took part in a workshop of the Laird Youth Leadership Foundation, set up by Mr. Laird years ago to give college scholarships in the district.

“The boys and girls were subdued and monochromatic by the standards of New York or Boston or Chicago — hair neat, wearing ties and jackets, pinafores and charm bracelets. A local Republican professional remarked.”

So, yeah, the article sort of goes on to talk about how they have all this anxiety about the changes happening, which is to say, the black uprisings in major cities, specifically throughout the North, the Midwest, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, and that there’s this kind of look of, you’ll see this in the TIME Person of the Year article, there’s this constant era of hand wringing about like anxieties, without any understanding that okay, I don’t want to totally flattened the class distinctions between whites, because I think those are a meaningful undertone of what’s being talked about here, but setting that aside, there’s this thing where white culture dominated or white people were the central figure, I mean, television, film, literature, journalism, the default was white for centuries at this point, right? And that dominance went from 100 percent to 99.5 percent and now it’s panic time. It’s like freakout time, right? That ‘the Blacks are getting uppity, the women are burning their bras, and I don’t know what the fuck to make of this whole thing.’ And instead of saying, ‘These are very moderate asks, Jim Crow really oppressed Blacks in the South and racial prejudice in the Northeast,’ it says, ‘Okay, now we need to sort of coddle the white masses who are now scared of change’ and for some bizarre reason, instead of calling that white reactionary politics or white grievance politics or a whiteness as a political ideology, we’re gonna keep calling it the “heartland” or Middle America and it’s a weird sort of sleight of hand because if we talked about it as a project of whiteness, I think we would have a far more honest conversation, but you keep noticing the media, especially in the context of Richard Nixon’s win in 1968, constantly refuses to speak about it in explicit racial terms and to the extent race is talked about, it’s like a subcategory, maybe mentioned in paragraph 37, and race — which was common at the time, and to a large extent still exists today — race as a “concept,” quote-unquote, is this equal playing field where blacks and whites are kind of fighting for territory, it’s not seen as a form of oppression by one party to another, which is where the term middle America comes in, heartland’s close cousin, middle America. Middle America was coined in 1968, as we mentioned by Joseph Kraft, who was a columnist, but really became the new buzzword in 1969, when TIME Magazine named middle Americans their time Person of the Year and I want to read the intro from that, because it really I think, kind of cuts to the, it’s so vague, it’s like in typical kind of TIME Magazine fashion, right? This is a magazine that made its bread and butter off bullshit generational discourse. TIME Magazine, from the beginning, was always about arbitrating the extremes and telling you what the center is. Typically that center was pro-empire, moderate liberal race stuff around the margins, but was basically maintaining the status quo.

Here’s the opening paragraph to their 1969 Person of the Year, “The Middle Americans”:

“THE Supreme Court had forbidden it, but they prayed defiantly in a school in Netcong, N.J., reading the morning invocation from the Congressional Record. In the state legislatures, they introduced more than 100 Draconian bills to put down campus dissent. In West Virginia, they passed a law absolving police in advance of guilt in any riot deaths. In Minneapolis they elected a police detective to be mayor. Everywhere, they flew the colors of assertive patriotism. Their car windows were plastered with American-flag decals, their ideological totems. In the bumper-sticker dialogue of the freeways, they answered MAKE LOVE NOT WAR with HONOR AMERICA or SPIRO IS MY HERO. They sent Richard Nixon to the White House and two teams of astronauts to the moon. They were both exalted and afraid. The mysteries of space were nothing, after all, compared with the menacing confusions of their own society.

“The American dream that they were living was no longer the dream as advertised. They feared that they were beginning to lose their grip on the country. Others seemed to be taking over — the liberals, the radicals, the defiant young, a communications industry that they often believed was lying to them. The Saturday Evening Post folded, but the older world of Norman Rockwell icons was long gone anyway. No one celebrated them; intellectuals dismissed their lore as banality. Pornography, dissent and drugs seemed to wash over them in waves, bearing some of their children away.

“But in 1969 they began to assert themselves. They were “discovered” first by politicians and the press, and then they started to discover themselves. In the Administration’s voices — especially in the Vice President’s and the Attorney General’s — in the achievements and the character of the astronauts, in a murmurous and pervasive discontent, they sought to reclaim their culture. It was their interpretation of patriotism that bought Richard Nixon the time to pursue a gradual withdrawal from the war. By their silent but newly felt presence, they influenced the mood of government and the course of legislation, and thus began to shape the course of the nation and the nation’s course in the world. The Men and Women of the Year were the Middle Americans.”

So there’s a lot going on —

Nima: Literally could have been written in 2017 or 2021.

Adam: “Middle America,” like “Heartland,” is both everything and nothing. It’s what you want it to be for the time, and again, this is typical of the sort of Newsweek, TIME Magazine, middlebrow, cultural writing, right? This is sort of a trend piece. They invented the ‘Boomers are doing this’ and ‘Generation X is,’ I mean, it’s bullshit, right? It’s bullshit pseudo politics, because this is all various ways of not talking about white reaction to black people asking for a modicum of baseline dignity, and economic security, which has been denied to them for decades, right? Or wanting to end a war in Vietnam that was genocidal that ended up killing three million Vietnamese. These are considered sort of radical demands, and the middle American just wants his country back, which he feels is quote “slipping away.”

Nima: Right, exactly and the article even gets more explicit while being still full of dog-whistles. So there’s a section headlined “Race,” and it says this:

“The rising level of crime frightens the Middle American, and when he speaks of crime, though he does not like to admit it, he means blacks. On the one hand, Middle America largely agrees with the advances toward equality made by blacks in the past ten years. Says Robert Rosenthal, an insurance auditor in New York City: ‘Sure, I know it’s only a handful of Negroes who are causing the trouble. Most of them are the same as whites.’ His daughter Nancy, 17, attends a school that is 60% black, and she expresses both the adaptability and anxiety of the Middle Americans: ‘I always look down the stairway to make sure no one is there before I walk. It’s not really bad, except that you can’t go into the bathroom because they’ll take your money.’

“Middle Americans express respect for moderate black leaders like Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young — which is easy enough. Middle Americans would generally like to see the quality of black education improve. But the idea of sacrificing their own children’s education to a long-range improvement for blacks appalls them. ‘They moved to the suburbs for their children, to get fresh air and find good schools,’ says Frank Armbruster. But programs such as bussing ‘negated all their sacrifices to provide their children an education.’” End quote.

Adam: Yeah, this is perfect, right? This is exactly what the purpose of these terms did, and still do in many ways, which is they whitewash the far-right ideology being advanced, ‘they would love to watch the Negro be more educated,’ how the fuck do you know that? What are you basing that on? That’s just ‘Oh, they want them theoretically to be better educated, but they don’t want them to bus to their schools.’

Nima: But not if it changes their lives at all.

Adam: Yeah, it’s assuming a degree of sacrifice, which is not really real, or that like yeah, they theoretically sort of want these things or at least they hand wring about them, which is all they really care about because you don’t want and they insist on several occasions these are not Wallacites, they are not George Wallace voters.

Nima: Right. So they’re not your, you know, Jim Crow segregationist Southerner, they’re just your average Joe who wants life to be normal and uncomplicated and the article, which I encourage all of our listeners to read in full because it is quite dazzling, continues this way:

“The gaps between Middle America and the vanguard of fashion are deep. The daughters of Middle America learn baton twirling, not Hermann Hesse. Middle Americans line up in the cold each Christmas season at Manhattan’s Radio City Music Hall; the Rockettes, not Oh! Calcutta! are their entertainment. While the rest of the nation’s youth has been watching Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy, Middle America’s teen-agers have been taking in John Wayne for the second or third time in The Green Berets. Middle Americans have been largely responsible for more than 10,000 Christmas cards sent to General Creighton Abrams in Saigon. They sing the national anthem at football games — and mean it.

“The culture no longer seems to supply many heroes, but Middle Americans admire men like Neil Armstrong and, to some extent, Spiro Agnew. California Governor Ronald Reagan and San Francisco State College President S.I. Hayakawa have won approval for their hard line on dissent. Before his death last year, Dwight Eisenhower was listed as the most admired man in the nation — and Middle America cast much of the vote…”

Adam: What’s so weird is that throughout this article, they list these major pop culture products after they say that the pop culture doesn’t represent their values.

Nima: Right.

Adam: They’re like, Hollywood ignores them, but then there’s this huge John Wayne movie called The Green Berets that Hollywood made, like someone’s making this or they don’t like this avant garde theater, Oh! Calcutta! so they go see the Rockettes. Well, the Rockettes are still being produced in New York City.

Nima: So, much of the kind of game is given away by the fact that so many people who are quoted in this TIME piece, this Person of the Year “The Middle Americans” piece,which was published right at the beginning of the year in 1970, is that so many of the people quoted are from New York or are in New York. So again, it is not really about geography, right? It’s about sociology. It’s about the ideology of whiteness.

Adam: Well, it’s the definition of smarm, right? The reason why Pete Buttigieg says, ‘I’m from the Heartland,’ he’s mugging, it’s the textbook definition of smarm. It’s a smarmy invocation, in 90 percent of the examples we’ve found in media people evoking the heartland or middle America they themselves are not actually from the heartland or middle America. It’s a way you smuggle in your own conservative ideology. It’s sort of like Bill Maher’s whole white working-class, right? Which we could do a whole episode on, white working class is similar, where you say, ‘Bernie Sanders is not going to fly in the heartland.’ This thing that I don’t like I’m going to take my worldview, my reactionary worldview and then projected onto some vague cohort of puerile America and tell you why I’m going to oppose that thing. So when you say it, you’re mugging, right? When Pete Buttigieg says, or Amy Klobuchar says ‘I’m from the Heartland,’ it’s a totally vacuous phrase, it doesn’t mean anything. To say nothing of the fact that the motherfucker’s from South Bend and his father’s a Gramsci scholar, so shut the fuck up, but whatever, that aside, like it’s pure smarm, because it’s sort of saying, ‘I’m a real American. No, I’m not from Oakland like Kamala Harris. I’m not from Brooklyn, like Bernie Sanders. I’m from the sort of wink wink. I mean, you know what I mean? Frankly, it’s fucking, these terms are extremely anti-semitic. I feel like we’d be remiss not to stop and talk about that, but, to me, it’s very much about not, especially when people talk about like media elites, I think we know who they’re talking about when they say that.

Nima: It’s the Jews in New York and the Blacks in Oakland. They even mention, you know, the article says this:

“Middle America’s villains are less easily singled out. Yippie Abbie Hoffman or S.D.S. leaders like Mark Rudd are hardly important enough by themselves to constitute major devils. With such faceless groups as the Weathermen, they merely serve as symbols of all the radicals who pronounce the country evil and ripe for destruction. Disliked, too, are the vaguely identified ‘liberals’ and ‘intellectuals’ who are seen as sympathizing with the radicals. Perhaps the most authentic individual villains to Middle America are the Black Panther leaders, Eldridge Cleaver and Bobby Seale.”

So there is this acknowledgement of Black liberation, of Black power, of Civil Rights being the real thing that is scaring the quote-unquote “middle Americans.” Now it is clear that they’re talking about white Middle Americans, it’s clear they’re talking about whiteness as an ideology, as a project in itself, but that is not identified. It is all of these things that say it without saying it, and laundering the idea from TIME Magazine and other writers who wrote about this incessantly at the time and still now, that it’s all about being in — where else? — the middle, right? Middle America, but middle of the road, the center. It’s not about the radicals. We’re not Wallacites who like lynching, and we’re also not Eldridge Cleaver, right? So, who is in the middle and it always comes back to this quote-unquote “Middle American” regardless of where they actually live, where their families emigrated from, what industries they work in, it all has to do with opposing the liberal and intellectual elites, which is oftentimes code for Jews, and of course, quote-unquote “Black militancy,” and TIME Magazine itself says quote, “It is the black militants who especially anger the white middle.” It is clear what is being discussed here and still equivocated for.

Adam: The concept of the heartland was constantly referenced by Richard Nixon himself. I mean, there’s article from July 1970 in The New York Times:

“During one of a series of quick interviews for local television and radio stations, Mr. Nixon declared himself happy to be back in the American “heartland.” Fargo thus became the fourth city to receive that designation since Mr. Nixon began, as he puts it, ‘taking government to the people.’ The others were Indianapolis, St. Louis and Louisville.”

“The people” presumably being in the heartland, not people outside the heartland not being people. Ronald Reagan in his 1984 campaign, his whistle stop tour, his train was called The Heartland Special. That same year in 1984, a confederation of chemical, oil, tobacco companies founded The Heartland Institute, a far-right think tank that still exists today. The wholesome sounding Heartland Institute was central to discrediting science linking cigarettes to lung cancer and spent a lot of money on climate denialism throughout the years and still does. Over the years it’s been funded by the Kochs, Bradley, and the Walton families. The Walton Foundation loves this word heartland along with Brookings, they funded a Heartland Project where they were trying to determine what was the heartland and what the heartland wanted. You’ll be surprised to learn they want less corporate regulation.

Nima: Shocking.

Adam: In 2004, Bush kicked off his reelection with what he called a Heartland Tour. So I’m reading from a CNN article in July of 2004 in Springfield, Missouri:

“A day after John Kerry’s acceptance speech at the Democratic convention, President Bush began a month long push to his party’s event with a visit to America’s heartland. At a Republican rally in Springfield, Bush defended his record in office, took shots at Kerry and underlined his conservative views and values. Bush told cheering supporters Friday that ‘there’ll be big differences in this campaign. They’re going to raise your taxes; we’re not. We have a clear vision on how to win the war on terror and bring peace to the world,’ Bush said. ‘They somehow believe the heart and soul of America can be found in Hollywood. The heart and soul of America is found right here in Springfield, Missouri.’”

Wink, wink. Wink, wink.

Nima: (Laughs.) So much of this, whether it’s the TIME Person of the Year piece or that same year 1970 there was an ABC News special for their now mini series called “Straight from the Heartland” and further kind of pushing what is genuine, what is authentically American in their own press release, which is rife with dog-whistles, of course, it says this, “Those who live in the American heartland are often considered honest, sincere, cautious, conservative, individualistic, hard working, and religious.”

Adam: Right. So the people who aren’t are not honest? I mean, obviously, time and time again, they associate whiteness with good moral virtue.

Nima: And this is still happening today. When Claire McCaskill was quoted as saying, “Free stuff from the government does not play well in the Midwest,”it was pointed out that well, you know, Representatives Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar, people like Representative Lloyd Doggett from Texas or John Lewis from Georgia, they may not fit neatly into those kind of categories. Veteran Washington journalist from The New York Times Jonathan Weissman tweeted this: “Saying @RashidaTlaib (D-Detroit) and @IlhanMN (D-Minneapolis) are from the Midwest is like saying @RepLloydDoggett (D-Austin) is from Texas or @repjohnlewis (D-Atlanta) is from the Deep South. C’mon.” So again, this is a journalist for the Times deciding who is allowed to be Midwestern, who is allowed to be Texan, who is allowed to be Southern, and of course, it’s not going to be those who are not the kind of quote-unquote “Middle American” of Heartland lore.

Adam: Yeah, it’s clearly so Midwest again, which we haven’t talked about yet, but Midwest is very much in this camp, right? It’s a proxy for whiteness. So when people say, ‘Oh, well Rashida Tlaib is from the Midwest,’ your brain starts to fry and you’re like, well, no, that can’t really be because the Midwest isn’t an actual place, it’s a political shorthand for the protection of white identity politics. He later apologized for this and such but, you know, one of the things that it does is it permits and then it’s also used to left punch, and it’s also used for the purposes of smarm. So we’re gonna play a clip that we played, I think, on the show once before of Samantha Bee left punching protesters after Trump’s win for being violent. We want to play this clip real quick in order to listen to it, I want you to look at who is important, who’s the constituency that the left must build its strategy around?

[Begin Clip]

Samantha Bee: Oh, god damn it, there is nothing the left can’t lose, including the moral high ground. If you jerks are just trying to get all your anarchy shit out of the way before President Trump gets control of the FBI, I hate to tell you this, you’re too late. You just gave Middle America an excuse to dismiss all these peaceful protesters as undemocratic sore losers. Thanks.

[End Clip]

Adam: Yeah. So here, we give an excuse to Middle America, which is white people, and it’s like, okay, maybe? But why don’t you just say that, say the thing you really want to say, which is why this is another quintessential smarm moment. It’s a smarmy thing to say because she’s interjecting herself as the arbiter of what middle America will and won’t like, not sure how one gets that status, but presumably, lots of people in the media seem to have it, and it’s like, why don’t you just say you don’t like it? Say that you personally don’t like it or you find it vulgar or you don’t like protests that break windows, like say what you want to say, don’t try to speak through Middle America, and that’s kind of the thing I find most grating about it is that not only does it obscure conversations about whiteness as something to be preserved and protected, it obscures people’s own conservative opinions. So that’s why it’s such a great propaganda term because it’s so nebulous, it’s so porous, so it can kind of be whatever it needs to be.

Nima: It’s also fundamentally ahistorical. And so, to that point, we are now going to be joined by Kristin Hoganson, a Professor of History at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She is the author of a number of books including Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920; American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century; and Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. Her latest book, published in 2019 is The Heartland: An American History. Professor Hoganson will join us in just a moment. Stay with us.

[Music]

Nima: We are joined now by Kristin Hoganson. Kristin, thank you so much for joining us today on Citations Needed.

Kristin Hoganson: It is great to be here.

Adam: So, I want to begin by kind of defining terms, which is obviously central to this episode in particular, but also how we sort of evoke these concepts, you note that the idea of an American heartland was kind of adopted from popular usage of Eurasia or Russia, the Russian heartland post-World War Two, and then began to sort of slowly evolve and sort of peak in the ’60s as a kind of counter to the LA-New York-DC, and its positioning within a kind of post civil rights, white identity politics for lack of a better term. So I want to sort of talk about when someone evokes the word “heartland,” as we argue in our introduction, it sort of has a double meaning, sort of heart is in the center of the country, geographically, but also heart in a sense that it’s the moral center of the country, kind of untainted by the excesses of the coasts, e.g. immigrants, Jews, I think there’s about a dozen different dog whistles we can get into. What do you think the image being evoked is by the heartland, when people say that term, and what do its origins tell us about what the political utility of the term is?

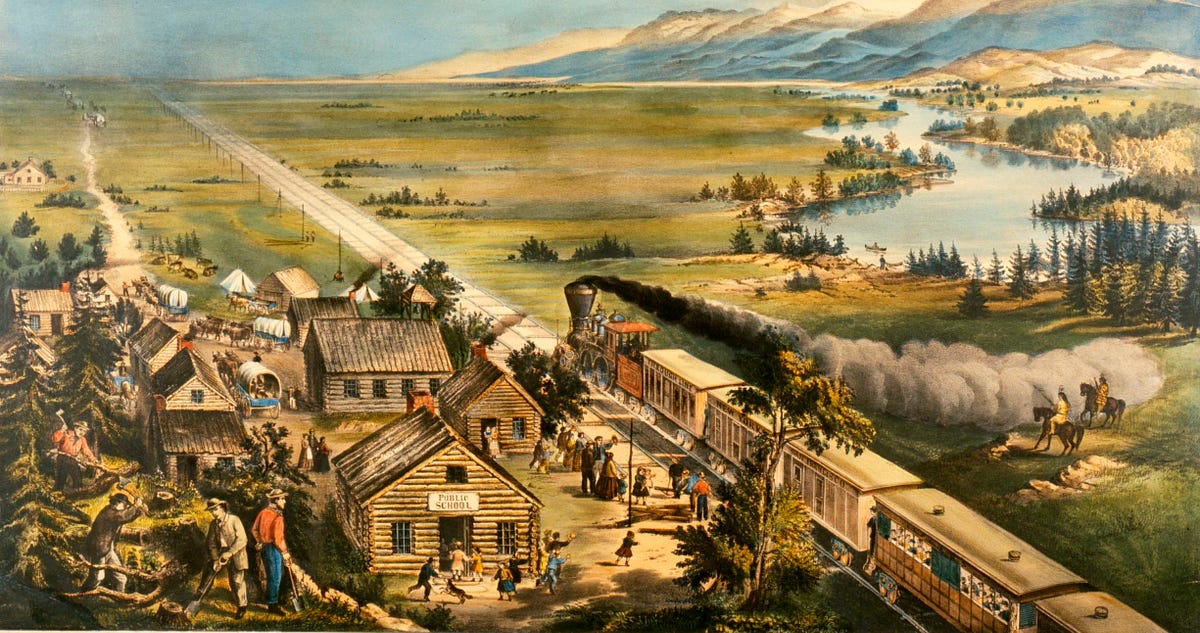

Kristin Hoganson: Yeah, so you’re totally on to something when you say that it seems to be a geographic term, but that is really about values, and that the backstory was a backstory about geostrategy. So the term first originated with British geographer, Sir Halford Mackinder, who in 1904, developed the term in reference to global power and his argument was that whoever controlled the Eurasian heartland would control the world and that was a counter to navalist theories that held that naval power was the key to global power and then during World War Two, it referred to the struggle to control Central Europe and then in the Cold War it is used in the United States to anxieties about Soviet domination over Eurasia. So the backstory of that term is all about global power and what it was first adopted in the United States in reference to the United States after World War Two, it was about global power. It was about the industrial heartland, and it was about U.S. dominance and the Cold War. But at the same time that that term took off in reference to US power, it also began to refer to this nostalgic, nationalistic place and eventually was that rival understanding of the heartland that emerged triumphant and in that idea of the heartland, it was all about real America and the entity that was held up in opposition to the heartland wasn’t just foreign rivals for global power, but it was exactly as you said, it was people of color, it was non-Christian people, it was about urban industrial workers as being excluded from real America. And the term then came to be affixed not so much to centers of industrial production to the great industrial manufacturing cities of the Midwest, but rather to the rural Heartland and then in that more nostalgic, soft focus heartland, it was all about family farmers, people of Northern European descent, people who were Christian, who seemed to represent some kind of quintessential Americanness and that is, I think, the sense in which the word heartland is typically used today, as a term with mythological significance, right? That is bigger than just some kind of geographic reference point, but is used politically to convey a sense of who counts as an insider in the United States and implicitly then who are outsiders who don’t really and fully belong.

Nima: Yeah, I think to that point, you write so much about, you know, in your book, how it’s really about the beating heart, rather than say, maybe the bleeding heart, but it’s all about hay rides and farmers markets, not obviously like the Haymarket Riots, and you really kind of center in on corn, cattle, and I guess maybe for lack of a better term, capitalist pigs, and how these commodities kind of being produced in this quote-unquote “heartland” are then connected to the growth of American power and American Empire. And you kind of talk about how seeing this Middle America, this heartland as being almost isolationist in our political imagination in the propaganda that we hear, that it’s all about this heartland/homeland, right? And yet, as you’ve written, Kristin, there is so much to do with this geographical space, and the people who live there and produce there and the growth of American Empire. Can you just kind of dissect that a bit?

Kristin Hoganson: Let me begin with some Trump rallies and some of the things that he has said in the rallies including in places like Ohio, I think a lead narrative is about victimization, and how the heartland has been victimized by the rest of the world and that one of the things that he promised to his base is that he would end that victimization and I think in those narratives, what gets lost is that the United States has exercised tremendous global power, right? That the history of the United States in the 20th century world is not just one of victimization, but it’s the story of a superpower that has really profoundly impacted the lives and well-being of people in other countries. And I think the heartland myth is at the base of those claims, because I think a key component of it is that there is an isolated core at the center of the country that is this buffered place that has been protected from the rest of the world, that the people there are profoundly isolationists in opposition to coastal elites, who are the capitalist class, who have investments and financial commitments to other parts of the world, and that real America is inward looking and cut off from the rest of the world. And insofar as you look at histories of development over time, I think an older narrative has been that people have progressed from being profoundly local in many ways and then over the course of time increasingly connected to the nation, and then ultimately to the rest of the world, especially with more consciousness to globalization starting in the late 1980s. But if you look at the histories of the animals you were just talking about, the cattle and pigs, and also things like soy, which was imported from East Asia, the early seeds in the early 20th century and other forms of agricultural production, the vast majority of the genetic material was imported to the United States, much of it in the 19th century as a result of scientific agricultural breakthroughs, and more bio prospecting in other parts of the world for genetic material that can be used for profit in the United States. And so I guess the point of all this is that this seemingly local and isolated core really has never been local and isolated, that from the very get-go, it was connected to larger currents. And if you go back even before the establishment of the United States, the indigenous people who lived and many of them continue to live in what is now the heartland, were not local in any sense of the word that would make sense to us now, that they had trade connections over vast distances, and in many cases were highly mobile, and traveled widely through space and locality was not really, you know, a vocabulary word. It wasn’t a concept. And it was something that was introduced by the pioneers who by definition, were people who came from somewhere else, who like to consider themselves pioneers because it hid the colonial aspects of what they were doing and who struggled to define themselves as local, they had to invent the idea of themselves as being local as a way of claiming rights and belonging. These would be the indigenous people who they were displacing, and then over the generations in opposition to immigrants and other people who were coming into their communities, making their own rights claims. So the very idea of the heartland being a profoundly local cut off place hides histories of connection that predated any kind of establishment of locality.

Adam: Yeah, which I think speaks to one of the things I find fascinating, which is this undercurrent of, retconning in white indigeneity, which I find weird parallels with South African propaganda, pro-Apartheid propaganda in the 1960s to 1980s, which is they say, ‘Oh, well, the Dutch settlers had been there forever,’ it was kind of timeless that they actually predated African tribes in some senses and it seems like the obsession with the heartland in our sort of collective vision has a lot to do with creating this idea of a kind of timeless, white North American establishment that almost makes it, like you said, the true America or real America, right? Sarah Palin had a “real America” comment, that it sort of gives more moral purchase to the broader settler colonial project, because it kind of grounds the white majority into a place where it sort of feels like it’s always kind of been there. I want to sort of talk about the value of having this real America as a sort of timeless concept that we can refer to, and what it says about, for lack of a better term, that what this sub-myth says about the broader myth of manifest destiny in North America, and why having a heartland sort of is essential to that project.

Kristin Hoganson: Yeah, so that’s so interesting, you know, thinking about the comparisons with South Africa and the retroactive continuity. I definitely think you’re onto something with that and one of the things about the heartland is that the term is used more in nonhistorical contexts, I think, then and historical analysis. So I think it has come to apply to a kind of a fictive place, an imaginary place that serves ideological functions, and in that sense, it’s not really an explanatory word that helps us understand historical processes over time, right? So in seeming to be static and timeless and essential, it hides how Midwestern states have come to be the way they are today.

Adam: Yeah.

Kristin Hoganson: So it hides histories of settler-colonialism, it hides histories of killing and displacing indigenous people, it hides histories of prohibiting free Black people from living in states such as Illinois in the 1850s when there was legislation that forbade that, it hides histories of sundown towns in the Midwest that forbade Black people from living in places where they were allowed to work during the day, but had to leave at nighttime to keep towns all white. So in that sense, you know, just thinking about the heartland as an imaginary place that people assume they know because of all the kind of connotations of picket fences and apple pies attached to it, it hides how Midwestern states actually came to be whiter, at least in their rural areas, than other parts of the country and how they came to have populations and rural areas that were disproportionately, in comparison to the rest of the country, of Northern European descent. It has histories of federal land redistribution, of taking land from indigenous people and giving it to veterans or making it available to white people through land grant opportunities. So the point is just to agree in large part with your point about how the term kind of naturalizes things that have violent histories, and backstories in many cases, and also, in making the heartland seem to be real America or quintessential America, by making it seem like they are insiders and outsiders, how it continues to do really significant ideological work, that it seems to be a nationalist mythology, but I think from our own time period is easier to call it out as a white nationalist mythology that insiders who are included in the story do not look like the country as a whole. That is highly illusionary.

Adam: That’s what’s so annoying about the whole process. We spent the greater part of an hour talking about these concepts and what we keep coming back to is the idea that when people evoke the terms “heartland” and “Middle America,” which we can get into as well, then even I think, to a great extent in “the Midwest” as a sort of political shorthand, I don’t even think they mean white people per se. I think they mean whiteness as a political project, as a post civil rights political project and so much of these conversations would be very much clarified if people just said that. If they said, ‘This isn’t gonna play well in Middle America, Trump’s really popular in the Heartland.’ It’s like just say you mean people whose politics are centered around whiteness as a political project. You know what I mean? It’s a thought terminating cliche in its most pure form, which is to say it obscures far more than it elucidates and I find it very annoying when pundits use these terms and obviously we discussed at the top of the show, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar always mention the heartland, and it’s like, just say, you think that white people are more likely to vote for you than they are Bernie Sanders or Kamala Harris, and were viewed as being more exotic, you know what I mean? Like there’s a kind of chickenshit-ness to it that I find a little annoying.

Kristin Hoganson: Yeah, so it obscures not only the diversity of people who are living in the Midwest now, including small towns and rural areas, people who are working in things like meatpacking plants across the Midwest, it not only hides the present, but it also distorts the past, which was a multi-racial past from the very beginning of European colonization in North America. And in the past, it also was profoundly shaped not only by the kind of trade connections that I was alluding to earlier with the importation of genetic material, the export of agricultural products, but also, you know, the idea that it could be cut off from the Midwest from the rest of the world hides histories of how the United States as an imperial power wasn’t just a entity that exercise power beyond its shores, but the empire came home from the beginning to places, including the rural Midwest. So to take one example, in my book, I start with Champaign County in East Central Illinois, where I happen to live, and I follow threads that lead out from that place, and there’s a military base that was in the county that is shut down now, but was established as a military base in World War One and it was a place to train pilots to fight in France and the earliest aviators who came there to train the pilots were people who’d been serving under Pershing in the Mexican Expedition and been flying sorties into Mexico and so then they came to central Illinois to teach those flying skills and they were joined by people who’ve been serving in the US military in the Philippines and then they took their aerial expertise to France and the congressman who was representing the district at the time, William McKinley — who’s not to be mistaken for President William McKinley from Ohio, another Midwesterner who is, you know, the architect of American Empire around 1898 — but the William McKinley I’m talking about made 30 transatlantic trips in the early years of the 20th century, and he circled the globe three times, including stops in the Philippines and he went on various tours of the Caribbean to look at US island holdings in places like Cuba, Puerto Rico, visited Panama, and he was big on the speaker’s tour advocating American Empire, U.S. Imperial expansion, he was also big on the global governance, he was deeply involved in the inter parliamentary union, which advocated for global governance and he liked to speak in the county about, you know, he positioned himself as an expert on Philippine affairs and little did he seem to focus on there are actually a lot of veterans in his district who are veterans of the Philippine War and there were students from the Philippines who were studying at the what is now the University of Illinois and those students were networking with students from places like China, and Mexico and India and they were forming anti-colonial solidarities. So they come to the Midwest to study agriculture, as well as other subjects like engineering, it was not unusual for students to come to Illinois, that was a pattern across land grant universities, and the outcome was that places that are considered to be, you know, profoundly isolationist, disconnected from the rest of the world, became hotbeds of anti colonial activism, even in the early years of the 20th century and all those kind of histories of connection are not well known by people, including people who are living in the communities where this is part of their history.

Adam: Well, yeah and part of the way you do that is by eliminating any vaguely urban area, sort of not counting this Midwest, right? Like you said, well, the IWW was founded in Chicago, that doesn’t count, Chicago doesn’t count.

Kristin Hoganson: Oh, yeah.

Adam: Well why? ‘It’s not part of the Midwest. It’s not part of heartland.’

Nima: Well, right. As you write in your book, you know, there’s so much tied to what you discuss as being these local histories, which, you know, you’ve been referring to but I’d love to kind of hear a little bit more about this, the othering and belongingness of how local histories are written and how the local histories that we see of middle America, the Midwest, the Heartland, become almost like this mythologized nationalist history, because they rely on, you know, as you yourself have written, “The establishment of churches, courthouses, schools and parks all merit mention, as do gleaming hospitals, depots and streetcar lines.” But these histories make nearly everyone within their orbit look good by sleighting everyone who didn’t fit the proper mold, right? And so can you talk about how these local histories have kind of informed a larger national mythology and how they really serve, as you say, norm-making and boosterish ends?

Kristin Hoganson: Exactly. So one of the things I was trying to get at in the book was where did the idea of the heartland come from? And it seemed like local histories were the antecedent and the vein of thinking that made things like the heartland myth possible. I don’t want to slam all local history, right? There are incredibly insightful, well researched analytical accounts that can change your worldview, that can help you see the world if not in a grain of sand, then at least in a very different way and I want to celebrate and applaud those forms of local history, and also to celebrate local histories that can help people understand things like difference or their place in the world or their connection to the broader streams of history. So I’m not trashing all local history. But I am very critical of antiquarian forms of local history, which are the kinds of, what you were just talking about, like when was the first school built, when did the streetcar line go in, who built which church and so forth, and those types of local history often are all about deciding who are the insiders, and who are the outsiders and the insiders are typically the people who literally own the place, right? They’re the property owners. And they feature very prominently in 19th century local histories, many of which were produced by commercial agents, and they wanted to sell the books to the people who buy them, who are the people with money and so huge parts of those local histories are mini bios of the leading fathers and they tend to be bad in the community and they write out Native Americans, including people who have ongoing connections to various communities, they write out people who don’t own property, anybody who doesn’t fit into the normative, you know, ideals of who should be celebrated in the community, they’re completely excluded, and working class transient people, women do not figure largely except for like women as family members of wealthy people in these histories and beyond just like that exclusionary component, early local history set the stage for teaching people to think about bounded units of space. So they tended to take the geographic unit, whether it was a town or a county, as determinative, and the history is its color inside the line kind of history, right? You know, so whatever the boundary of the town or the county is, that’s where the story starts and ends. And you just read about things that exist in that space and the possibility that each of these little patches is stitched to larger fabrics, just does not figure into these local histories. Let me reminisce for a second about when I was in graduate school in the 1980s, which was a time period in which local histories were really in vogue, in part because of the ability to do more of computer assisted big data research and community studies, and I remember being in a discussion at one point about like, what about the people who left? And the answer was, well, they’re hard to trace, right? So now we can look at church records and figure out average lifespan, fertility, age of marriage, things like that, and do a lot of number crunching in that respect. But to trace people when they left was understood as a technically very difficult thing before internet and digital searching made it more feasible. But even then, a lot of people who left were indigenous people who were kicked out and all those records are organized by tribal name, and it would be very easy, even prior to current digital searching methods, to trace a lot of those histories but that wasn’t part of the mindset, right? That was a legacy of an older vein of local history writing, which was all about, you just look in and don’t have a kind of dual vision where you look in and out and I think that mode of thinking is behind the heartland myth in not only in so far as it’s exclusionary, only some people matter and other people’s histories are assumed to be not so important to the core story, or those people are considered to be not as worthy as others, but also in the kind of relentless effort to think that we can fix a story inside of set boundaries and not pay attention to how seemingly national stories have unfolded in imperial spaces and global spaces. Which is, you know, one of the things that became so apparent to me when I was researching the book is that it really was a global history, even though it started and ended with a very small county.

Adam: This touches on I guess provincialism is a theme we talked about a lot. We did a whole episode on the kind of political currents of contemporary popular country music and one thing that we kept coming back to is this idea of nostalgia and the political potency of nostalgia and it seems very much that much of the discourse, the contemporary discourse, the sort of Nixon era onward, Reagan’s whistle stop tour the train was called The Heartland Special, Bush had his Heartland Tour, I mean, so there’s a sort of an aching for some time and of course, it’s never specified what that time is because I think if we had to do the messy work of specifying the time period, it would be clear what our political goals are, right? “Make America Great Again” being the ultimate manifestation of that kind of nostalgia. Can we talk about the sort of nostalgic properties of the term “heartland” and the other close cousins we’ve been talking about, which is sort of Midwest or middle America, how does nostalgia play into this concept of a heartland and to what extent has this idyllic world ever existed or can it come back again for a certain set of people?

Kristin Hoganson: Yeah, well, it can never come back again, because it never existed in the first place.

Adam: Right.

Kristin Hoganson: Which I can elaborate on that, but I think the lens of nostalgia makes the heartland seem essentialist and fixed in time and so the idea that it has developed over time, that there are histories like what I’ve been talking about, of dispossession, and forced removal and violence, that gets hidden if it’s just some kind of mythical timeless, quasi family farm picture that comes to mind. It is outside of history, right? And if something is taken outside of history, it takes it outside of rational, empirical analysis, right? It’s just an imagined projection and not something that’s actually based in any kind of evidence that can actually help us understand how things got to be the way they are today in a better way, and actually understand how things are today. And part of it, I think, with the nostalgia is it makes the heartland seem to be a very safe place, right? It’s a quintessential safe place in some respects. But it’s not the safe place for everybody, right? If we understand the rural heartland, and I am talking about the rural heartland in all these comments, as generally Northern European descended kind of place, then that hides all the ways in which it has been a really unsafe place for other people, with indigenous people in the time period that I study, the 19th century, being a foremost group for whom the heartland was not a safe place, quite the opposite, right? It was a place of unrelenting violence, and that gets hidden in the kind of nostalgic understandings of the heartland as the place where real America can be found. It contributes also to ideas of go-it-alone-ism, right? If you take the heartland out of history and think that it’s just someplace that has always existed in its own kind of pure form, it prevents us from understanding all the connections and alliance politics that human migrations, the capital investments, the imported engineering technologies, the export markets, a trans-imperial solidarities that link the people who did well economically in the heartland with imperialist powers in Northern Europe that may have been rivals in some respects in the North Atlantic, but if you tilt the access to a North-South axis, they were definitely working in solidarity with each other, and you know, in very cooperative non isolationist ways. All that gets hidden if you take the heartland out of history, and just put it in the realm of nostalgia. And just one final comment on that is the word heartland, I think often with the idea of the heart in the middle, makes people think of some kind of fixed core, right? That the heart is a spiritual thing, it’s not just a muscle, but it’s metaphoric, right? It’s about an inner nature or a true essence or who you really are at heart or what the nation really is at heart, and so at least the ideas of fixity that, again, take the heartland as this mythic place out of the wider fabric of history. But I think there’s a different way of looking at a heartland, and that’s to think about the heart as the circulatory organ, right? It’s all about pumping and about circulation and about valves that kind of regulate the flows, right? So it’s not like the flows can go anywhere, anytime on an equal basis, but they’re kind of regulatory mechanisms that patrol borders or make it possible for a circulation to happen and that also prevent it in some cases, and I think that different way of thinking of the heartland is actually probably more true to the history of the place.

Nima: Yeah, I love that idea of kind of the arteries that go everywhere, and you really weave that throughout your book, the stuff that I keep coming back to are, you know, the advertisements for the railroad that’ll take you to New Orleans, so you can get to Panama, right? Or the idea that hog production in middle America is a civilizing industry, you know, that in the early decades of the 20th century there are things that you reproduce in your book, you know, from say, the Breeders Gazette in 1911 and it’s, “The American Indian never produced a hog, nor have the Asiatic tribes of wandering proclivities,” therefore, America as as a civilizing, colonizing entity. This from the Urbana Courier in 1918, “American food must complete the work of making the world safe for democracy.” And then perhaps my favorite, The Worlds’ Meat in 1927, quote, “Those nations which have been the most vigorous colonizers of modern times and which are the most advanced in the achievements of this industrial age are the heaviest meat eaters.” And that while meat eating “may not be the cause of greater virility… all racial evidence available indicates that the ordinary meat-eating races are the most virile races of the world.” This idea of virility and colonization and taming the wild finds this place in the heartland, but then as you say, bleeds out right all over the globe and I think that there’s this idea that we keep seeing time and again in our political discourse and, earlier in the show, we talked about how TIME Magazine in 1969 named “The Middle Americans” their Person of the Year, and the very next year ABC News at a primetime special called, “Straight from the Heartland,” there’s this shtick of really always coming back to the center and ignoring the rest, even though it’s broadcast that everything pumps outward. But there’s this idea that the press is always trying to find, you know, they did this with Nixon, they did it again, obviously, post-2016 with Trump, trying to pin down this mysterious silent majority that is really America and so what we see is, you know, the liberal journalists rush into small towns, Grand Island, Nebraska, for instance, and try and figure out why Republicans keep winning. Can you maybe talk about, you know, you talk about essentialism, and you criticize it throughout the book, and you kind of talk about this impulse of “liberal elites,” quote-unquote, on the coasts rushing to the heartland to listen to the beating heart of America and how that can be helpful, but also particularly reductive.

Kristin Hoganson: Yeah. So first, let me comment on what you were talking about with the “meat eating” and “virility.” That’s about global power. That’s the Mackinder view of the heartland. It’s all about exercising and projecting power over other people and those are the stories that get forgotten, that yearning for global power, the desire to exercise it, and in fact, the actual exercise of global power and, you know, deep involvement in that. As to your other point about people from coastal areas flocking to the heartland, yeah, I mean — what’s better? — the flyover jokes where the heartland just kind of gets written off all together, though not Chicago, of course, you know, not the urban heartland, but the rural mythical heartland is just Dullsville, not worth landing or the kind of patronizing we’re going to come in and figure out what’s really going on so that we’ll win the next election. I think there is a need to listen, frankly, I think that there are coastal and urban media biases and I have to say in working on the book, I would make my arguments about things like global connection and inter imperial connections, and I would get so much pushback. ‘Well, we all know that’s not true. We all know that they’re a bunch of like local hicks.’ This is not what I’m finding in my archival research. In these Breeder Gazette magazines, I’m finding that there are these dense networks of agriculturalists, there are agrarian solidarities that are not networked through Chicago, Chicago is not the nodal point, right? It’s like Springfield, Illinois, is more of a nodal point, or places where there are land grant universities are more nodal points for these agricultural networks, right? They’re just not on the radar screens of urban people because it’s not part of their, you know, economic universe and so I think, you know, in writing my book and speaking about it, I felt this pressure to reproduce the myth and so I want to acknowledge that, that I think that there are people in positions of media power, who are disconnected from various parts of the country, and, you know, continue to see other parts of the country through particular filters. But that being said, I also hear what you’re saying, where what you’re saying about people trying to find true America, real America, like they’ve bought into the myth in such a deep way, you know, that it’s affecting their reporting where they think they’re going to get the story if they talk to one person and don’t really realize the diversity even in rural places, not not only in places like Chicago, but in smaller towns and rural areas as well, that it’s a multi-vocal place. And in fact, the sense of not even knowing where the heartland is, right? That I’ve seen various pieces where people drive different maps of the heartland and no two maps look alike in part because it isn’t a set geographic unit. It’s not like something like the Great Lakes drainage basin or the Mississippi River drainage basin or the Great Plains or the wet prairies, you know, places that we could define with greater certainty. It’s a very fuzzy, vague, brass rods, sprawling, complicated place and so the sense that it could be kind of easily deciphered with kind of flyover reporting, I think is misleading and also, I think, I don’t want to go down this road too much, but I think one of the issues isn’t just the heartland, but it’s a rural urban issue and to suggest it’s all about the heartland just takes various politics and sticks them in the realm of this mythological space instead of what are the spatial areas and the political divides that are going on? And one more comment about what you were saying about listening, I think the issue is not only about coastal people going to rural and small town areas and listening, but I also think a challenge is for people in more legacy media, or well researched kind of fact based media to also be heard in some of these communities. I think that’s the flip side of the equation, right? If you look at the media landscape that people are operating in, I think it’s also just a disconnect with not only absorbing the mini stories of people in smaller communities in the Midwest, but also relaying the perspectives and politics of other communities in parts of the country, I see that as just as much of a of an issue.

Adam: Yeah, because the only thing I found slightly more grating than the parachuting in and doing the what-motivates-Trump-voter article was the sort of smug dismissal of that as a concept itself, because I think that’s also a problem, not to kind of equivocate here, but I also think that to me it’s not, I think the instinct is a good one, I think the impulse is a good one, because I think there were underlying features from the quote-unquote “heartland” or “middle America” that were missed. You touch on a lot of the trade policies, the inequities and trade policies that disproportionately hurt people in the Midwest or what we previously called the industrial Midwest, that I think were diminished or dismissed or mocked by pretty much every columnist at The New York Times, I think it’s fair to say, including the editorial board for 20–30 years. But it just seems like that the instinct is good, but then people rush in and then they they engage in these kind of reductionist cultural explanations that I think really are about reaffirming a fixed white grievance politics that we can’t really ever change or win over because if you can’t really change or win over, then you sort of all you can do is kind of witness the suffering and move on.

Nima: The Hillbilly Elegy-ism.

Adam: Yeah, pretty much and I guess that’s what I was getting. I don’t want to, I definitely don’t want to dismiss or rather I wouldn’t want to dismiss the idea of parachuting in per se, because I do think that’s a good instinct to have and Dean Baquet has talked about that, right? He sort of says, ‘Yeah, we have a blind spot. Of course we do.’ But anyway, I feel like we could do a whole episode on the weird obsession with meat as a proxy for manliness, but we’ll do that some other time.

Nima: (Laughing.)

Kristin Hoganson: Oh. I totally want to be part of that.

Adam: I’m not joking we may do that because Nima was reading them off to me and I was reading the ads in the book and I was like, this is weird. They’re obsessed with meat.

Kristin Hoganson: And the racial politics of it, like these animals were all racialized, right? The highend animals were racialized differently from the animals that were just brought to Midwest feedlots for fattening and and the backstory to that could take a whole episode.

Nima: The Chinese pigs and the Irish pigs. It’s incredible.

Adam: Yeah. We’ll definitely invite you back for that. Before you go, do you want to talk about what you’re working on? Obviously, you got a book published last year. You can talk about that a little bit or maybe what you’re working on next or what you got going on down there at the University of Illinois?

Kristin Hoganson: Yeah. So what is going on now at the University of Illinois is COVID-19 24/7 I have to say. So I’m director of Undergraduate Studies right now for my department and it has been just relentless around the clock labor with the shift to largely remote teaching and related COVID issues. But hopefully, eventually things will get better and then I’m hoping to write on the Great Lakes for my next books. I’m fishing, I guess, I’m fishing for leads right now.

Nima: I very much look forward to that. We have been speaking with Kristin Hoganson, Professor of History at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She is the author of books including Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920; American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century; and Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. Her latest, published in 2019, is of course The Heartland: An American History. Kristin, thank you so much again for joining us today on Citations Needed.

Kristin Hoganson: Oh, thank you so much. It’s really been fun.

[Music]

Adam: Yeah, I think I think the idea that, you know, this is why Northwestern University in Chicago is called Northwestern. It used to be the frontier, and the heartland as an aorta of imperial growth, which, of course, was unironically used up until it fell out of fashion in the ’50s and ’60s, it’s essential to its purpose, just as it was central to any kind of theories about dominance of Eurasia or the Eurasian continent in western Russia and Eastern Europe and it seems this idea of the kind of timeless yeoman farmer who’s simple and unpretentious and honest, you know, it’s just bullshit. It’s associating whiteness with moral virtue. I mean, that’s all it is. That’s all the term does.

Nima: And, you know, to Professor Hoganson’s point, and which you can read in her excellent book, is that the history of these places (and it’s all places) but determined by a kind of manufactured, mythologized history, is the white history of the place often absolved of settler-colonialism, absolved of empire building, absolved of racial oppression, absolved of xenophobia and anti-immigrant violence and policy on purpose because then you get this whitewashed — literally — history of a place that, again, is every place because it can be Manhattan’s Radio City Music Hall with the Rockettes all the way to a farmer in Napa, but as long as the values that are being proffered, the quote-unquote “values,” the quote-unquote “worldview,” is a white one, is a white nationalist and a white supremacist ideology, that is what Heartland means, that is what Middle America is meant to mean and that is what is signified whenever these terms are used in the press and political speechifying.

Adam: Yeah, so just say it. I mean, we have a very limited thesis here that we’re not even saying, say what you want to say. If I’m Pete Buttigieg and I’m Amy Klobuchar and I want to say that ‘I think I’ll do better with white voters because I’m white and inoffensive — ’

Nima: ‘And the policies that I promote are going to help them more than others.’

Adam: Right. Then say that, don’t give me this bullshit about how you’re from the Heartland like you’re in a fucking Hallmark movie. It’s so grating, it’s like, just be honest that we’re talking about white people and whiteness as an ideological project and say that, and let’s be honest about that and what the implications of that are and who that excludes from being able to use that moniker because I guarantee you it has nothing to do with the fact that you’re from South Bend, Indiana. That’s just a rhetorical cover for that.