Episode 107: Pop Torts and the Ready-Made Virality of ‘Frivolous Lawsuit’ Stories

Citations Needed | April 22, 2020 | Transcript

[Music]

Intro: This is Citations Needed with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson.

Nima Shirazi: Welcome to Citations Needed, a podcast on the media, power, PR and the history of bullshit. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam Johnson: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: Thank you everyone for joining us this week. You can follow the show on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed and become a supporter of our work if you are able to do that at this time through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson. We cannot thank you enough for continuing to support us, we know we are in a very strange new world right now so we are hoping that everyone is staying safe, staying healthy, and listening to as many podcasts that are called Citations Needed as possible.

Adam: Yes, during this trying time, we appreciate your support. We definitely are about 25,617 on the list of those on the front lines, but the content wars are important. Hopefully we’ll get you through this time with the content. I know there’s a lot of people who’ve messaged us and tweeted at us saying that they were home and they needed more podcasting, we will try to follow the news and make sense of it to the extent to which it intersects with media analysis. Now that we’ve all rallied around in the September 12, 2001 mode, we will gradually morph into the September 13, 2001 mode where we figure out who we’re going to bomb and how we’re going to infringe on civil liberties and all the fun stuff that comes with all sorts of crises.

Nima: And we will be there all along the way.

Adam: We’ll try to stay ahead of that because I don’t know Trump wants to go to war with China. I assume Russia will get involved somehow so who knows? But hopefully it doesn’t get that bad but, you know, you never know with this country.

Nima: “Woman Sues TripAdvisor After Falling off Runaway Camel,” notes the Associated Press. “Red Bull Paying Out to Customers Who Thought Energy Drink Would Actually Give Them Wings,” eyerolls Newsweek. “Tennessee man sues Popeyes for running out of chicken sandwiches,” scoffs NBC News.

Adam: We see these quote-unquote “frivolous lawsuit” stories all the time and have for many decades now. Seemingly absurd cases of get-rich-quick schemes often with catchy headlines, a caricature of a plaintiff-friendly legal system run amok. These stories play into faux-populist tropes of a country full of lazy poor people looking to cash in and a sleazy legal system that leeches off hard working Americans like you and me.

Nima: But how organic are these “pop torts” — or popular stories of frivolous lawsuits — and more importantly, how true even are they? What organizations are behind cherry-picking and teeing up these seedy and shameful tales of greed for uncritical writers, editors and producers to put out in the world? Who’s backing them, and what, perhaps, may be their ulterior motives?

Adam: Moreover, what are the human stakes to so-called “tort reform” and how did it come to be that the vast majority of Americans came to accept the premise that, at some point in the 1980s, we all became amoral, lawsuit-happy scumbags out to shut down Mom and Pop stores and grab a quick buck?

Nima: Later on the show, we’ll be joined by Joanne Doroshow, Founder and Executive Director of the Center for Justice & Democracy at the New York Law School. She is also co-founder of Americans for Insurance Reform.

[Begin Clip]

Joanne Doroshow: When it comes to medical malpractice and the problem of substandard care in urban areas and then the high rates of preventable medical errors in some of these areas, so when you make it more difficult for people to go to court and sue or limit what their compensation is, those who are receiving the substandard care are going to be harmed by that. More harmed than, you know, a corporate CEO in Greenwich, Connecticut, let’s say.

[End Clip]

Adam: I’ve been excited about this episode for a long time. I think that this is sort of a spiritual sequel to our episode on PC College Kids because it follows surprisingly a similar trajectory of who funds these things. Many of the same forces that fund all the PC college campus panic and it has a very similar propaganda pipeline where you have a sort of blanket surveillance system set up, in a sense, where you cherry pick the kind of more superficially appealing lawsuits, you pump them into right-wing funded kind of quasi media outlets or think tanks who then highlight those and then those funnel their way into mainstream media reports, New York Times and NPR, Washington Post and then those then inform the broader culture and then ultimately find their way into what the ultimate form of messaging is, which is pop culture: television, show scripts, et cetera. The obsession with frivolous lawsuits in the campaign for tort reform, has many of the same funders and serves a similar ideological ends and follows a very similar pattern of bad faith cherry picking, and disseminating that into kind of a broader cultural belief that, at some point, there’s always this nebulous point and I assume it’s in the ‘70s or ‘80s, where everyone got way too sensitive and weak and we just started complaining on college campuses, or in today’s episode, we just started suing everyone.

Nima: Exactly. I think the idea of “so sue me” and then turned on its head is this very common trope that has been weaponized. I think that weaponization is what is so often missed, that these are not necessarily always and most often not just reporters finding goofy or weird or pathetic stories that then they lift up and people all shrug and eye roll about bad faith gamers have the system, right? But so much of this is manufactured anger, deliberately pumped into our news and our entertainment by a network of think tanks, PACs, astroturfed concerned citizen groups, corporate syndicates and right-wing judges. This is not simply reporters digging up silly stories, and it is all meant to drive a sense of anger at the system at whomever it may be — your fellow citizen or these ambulance chasers — to then change the way that our justice system is supposed to work and somehow miraculously, the way this always needs to manifest is by getting rid of judges and juries that are on the side of people, and instead replacing them with those that side with corporations. But there is this myth undergirding this entire trope, the myth that people are slipping on ice and deciding to bankrupt mom and pop hardware stores that they happen to fall in front of, that this story of greedy, selfish, personal gain is ubiquitous. There’s this idea, because of the number of stories we see about it, that this happens all the time and it is dragging down our justice system. It is overwhelmed by these frivolous tort cases, but the reality shows something very different.

Adam: Yeah, I think important to begin by saying that there are several studies and indicators that tort law has, since the panic began, really in earnest in the ‘90s when then Governor Bush and then later President Bush in the 2000s started making this effort to push tort reform on a mass scale, that tort lawsuits have actually gone down quite a bit. So an op-ed in the Des Moines Register in June of 1995, noted that, quote:

The number of product-liability medical-malpractice and personal-injury filings have decreased in the last 15 years [since 1980]. Unless one considers child-custody, divorces and domestic-abuse matters to be ‘frivolous…’

— I guess those had gone up —

…one cannot blame the overall increase in litigation on unnecessary civil lawsuits. Frivolous lawsuits are rarely filed, and eventually they all fail due to an abundance of safeguards built into the system.

Unquote. And we’ll talk about what those safeguards are later. According to data from the Center for Justice and Democracy in 2008, tort cases represented only 4.4 percent of all civil caseloads in the seven states that reported these figures. The Center found that from 2007 to 2008, “tort caseloads fell by 6 percent in 13 general jurisdiction courts reporting, while contract litigation (often businesses suing businesses) increased by 27 percent.” Data from the National Center for State Courts indicates that between 1999 to 2008, tort caseloads declined by 25 percent in general jurisdiction courts reporting with contract caseloads rising by 63 percent in the same courts during the same period. So what you see is increasingly either tort law or civil personal injury suits have basically been steady, they haven’t really changed or they’ve gone down since the ‘80s whereas businesses suing other businesses have increased by quite a bit. But of course, businesses suing businesses don’t play into this get rich quick kind of welfare scheme framework so you never hear about that, which is the bulk of civil lawsuits. It’s Google suing Apple and the Koch brothers suing whatever, you know, what I mean, it’s corporations suing other corporations.

Nima: So let’s dig into this a bit. The idea of “tort reform” is itself an elaborate campaign designed to hinder people’s ability to sue a company or to collect damages from a lawsuit. “Tort” itself refers to a wrongful act that may warrant damages or an injunction, and the “reform” part of this in this case, is the euphemism for changing that — by which we mean gutting — that civil-legal system in favor of corporations. Now, state to state laws vary on tort and tort reform has a number of different subcategories. For instance, there is the idea of putting limits or caps on medical malpractice legislation or even damages, to limit the rights of patients who have been injured or killed due to malpractice and then put caps on the amount that people can be awarded if they win their lawsuit. Sometimes these caps are as low as $250,000, which seems like a lot, unless you’re talking about something that has fundamentally changed or destroyed your life. There are also pushes to limit non-economic damages. This means if a person is injured the calculation of their economic loss includes the consideration of wages or lost salary, not just in the past, but potentially in the future. So non-economic damages are meant to compensate for physical and mental suffering regardless of income. But here’s the thing, people with low or no wages are more likely to receive a greater percentage of their compensation in the form of noneconomic payments. Think about elderly people who are not working, think about children who get hurt, or harmed or killed, who aren’t making a salary at the time, all they have are non-economic damages and yet, tort reform seeks to limit those.

Adam: This point can’t be stressed enough that capping all non-economic damages effectively makes rich white men, by definition, way more valuable to the legal system and way more likely to get larger settlements than everyone else.

Nima: Another piece of reform are limits on class action legislation. Now class action is when a lot of different people come together to sue a company at the same time, some federal class action legislation has created significant limitations already on access to the courts for victims of discrimination.

Adam: So we’re going to go into the history of tort law. Tort reform was spearheaded by a cabal of medical, tobacco, and other industries starting in the 1970s. This was the result of several decades’ worth of changes to the civil-legal system that broadened individuals’ rights to sue businesses — one of the very few forms of recourse that they had to recover from corporate wrongdoing that caused damage to their lives. So the thing to understand about tort law is that as unseemly and as déclassé as it may seem, it is for most average people the only mechanism you have to hold corporations accountable for what they do to you. There is no real, you know, if DuPont poisons my water, and I want to get something out of it, if the EPA doesn’t sue them or they don’t get arrested by the FBI, which the likelihood of that is basically nonexistent, the only recourse I have as an individual with any kind of agency, as it were, is to sue them. So once you cap that, once you gut that, once you get rid of that the mechanisms of holding corporations accountable by individuals basically don’t exist and I think some people don’t really quite understand that, that it’s the last line of defense, that’s the last check against corporate power and without it, and we’ll show this later, without it, you have effectively no incentive for corporations and large industry to act in a way that’s ethical or doesn’t harm people.

Nima: In addition to being the last line of defense, it’s often the only because when you think about how government regulations have been destroyed and rolled back and gutted over the years, how that is itself a corporate campaign bolstered by politicians who advocate on behalf of companies rather than constituents, you already don’t have these checks in place. So oftentimes, the personal injuries suffered, are the only recourse that cannot only get some kind of recompense for individuals, but create change on a larger scale by holding companies to account. University of Virginia law professor G. Edward White has chronicled some of the changes over time in terms of tort law, which include workers’ compensation, strict liability, and comparative negligence. For example, workers’ comp first appeared when New York State passed a statute in 1910 modeled on an 1897 British law. Before this, workplace accidents were seen as a necessary tradeoff for getting business done and injured workers had no option for any kind of compensation like the ultimate sweat pledge from Mike Rowe, right? Your safety doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is that the bosses get the work done.

Adam: Then you have this concept of comparative negligence. This is a doctrine that there are degrees of negligence from minor to gross. According to White, quote:

Chronologically, comparative negligence surfaced approximately at the same time as strict liability for defective products, first being discussed in the literature in the late 1920s and ‘30s, and receiving support from prominent commentators by the 1950s. But comparative fault systems were not implemented on a large scale until the 1970s.

Thus, the birth of tort reform.

Nima: By many accounts, U.S. tort reform emerged on a state-by-state basis as an overwhelmingly right-wing phenomenon. Many names are attached to its origins, but so many of those names have to do with the John Birch Society, including the Koch brothers, Richard Mellon Scaife and Lynde and Harry Bradley, the brothers who founded the right-wing Bradley Foundation.

Adam: And where do we remember the Bradley Foundation? The Bradley Foundation, along with the Walton family and the Walton Family Foundation are two of the primary creators of the charter school movement, we discussed them at great length. The Bradley Foundation was behind Cory Booker’s first big profile position in the Black Alliance for Education options in 2000. They have their fingerprints on pretty much every right-wing thing you could possibly imagine. They are actually more socially conservative than the Koch brothers are. The Koch brothers, of course, are the Koch brothers. They need no introduction.

Nima: All this to say these are not just organic movements to change our legal system, rather, these are concerted conservative efforts. Dan Zegart in October 2004, wrote an excellent piece about tort reform in The Nation and he wrote this, quote:

The reach of the civil justice system expanded dramatically during the 1970s, but by the early 1980s a retrenchment was under way. The seed money for tort reform came from the same group of extremist multimillionaires whose family foundations nurtured the rest of the ultra-right’s agenda, especially David and Charles Koch, Richard Mellon Scaife and Lynde and Harry Bradley. Of the dozens of think tanks they created, four–the Heritage Foundation, the Washington Legal Foundation, the American Legislative Exchange Council and especially the Manhattan Institute and its Center for Legal Policy–took particular aim at plaintiff’s lawyers.

End quote.

Adam: A lot of what we cover on the show oftentimes is very evil, powerful people versus people with no power. Now, in the interest of full disclosure, it is true that this is not really the case here you have tremendous evil power and then you have on the other end of the equation some power, right? Plaintiffs, attorneys, and trial lawyers and personal injury lawyers or hold totally powerless, many of them, of course, are millionaires but comparatively, they’re very, very small time. It’s difficult to come across numbers that give an exact amount to sort of quantify the power but suffice to say that large fortune 500 companies oftentimes with legal staffs that are scores of lawyers have a lot of power, what they don’t have is visibility. They don’t have advertisements on TV. They’re not the punchline of every third joke in the ‘80s and ‘90s in sitcoms. They don’t have pejoratives like “ambulance chaser,” they’re kind of this evil behind the curtain that gets away with it because they’re not part of our kind of cultural Zeitgeist, right? And so the prevalence of personal injury lawyers is far exaggerated beyond their actual power, especially in what we’re going to talk about next, which is the origins of modern tort reform, which began in my home state of Texas, the trial lawyers were a major funding apparatus of the Democratic Party. And one thing you have to realize is that capping tort and undermining personal injury lawyers and trial lawyers, has a secondary, and I think even might get even argue a primary effect, of also undermining a primary funding base of the Democratic Party. So one of the founders of modern tort reform was a little known Texas billionaire named Dr. James Leininger, a medical supply business owner and member of a network of wealthy Texas conservatives who leveraged their immense wealth in Republican politics in Texas. Now, if there was one person who would want to undermine tort form, it would be a medical supply business owner. So a 2000 article from the Center for Public Integrity explored Leininger’s network of wealth and influence. According to the article, quote:

In the mid-1970s, the GOP claimed only one senator and two members of the House of Representatives and no statewide officeholders. Today, both senators, 13 of 30 members of Congress, and all 29 statewide elected officials are Republicans. Most of them, such as Perry and Cornyn, were financed by Leininger and handled by political consultant Karl Rove.

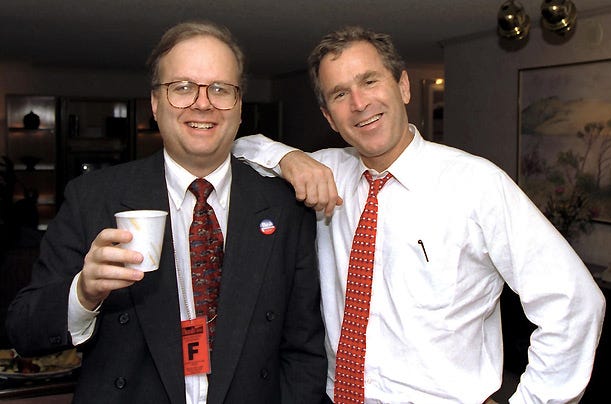

So you really can’t understand modern tort reform without understanding Karl Rove and Texas and how much that, it’s sort of like you can’t understand Cory Booker without understanding charter schools. You can’t understand George W. Bush without understanding tort reform.

Nima: And that article was written in 2000. Texas has gotten only more red in the years since. Leininger was also instrumental in the development of the tort reform campaign specifically, alongside the influential Karl Rove. Now remember, Leininger had a personal stake in tort reform: He and his business, a medical device company called Kinetic Concepts, had been sued dozens of times in malpractice cases, at least 60 times as of the writing of that article 20 years ago. 2000. He wasn’t the only one. The tort reform campaign was also attracting the attention and funding of other Texas industry tycoons, like William McMinn, Gordon Cain and J. Virgil Waggoner, who made millions in the Sterling Group, a Houston chemical company takeover firm.

As of 2000, Leininger had financed a half a dozen different think tanks and foundations with pro-tort reform policy positions. These include: Children’s Educational Opportunity America, cleverly abbreviated as CEO America, there is also a CEO San Antonio, Kinetic Concepts Foundation, Texas Civil Justice League, Texas Justice Foundation, Texas Public Policy Foundation. Leininger also created or helped fund 13 different political action committees or PACs to elect conservatives like aforementioned Rick Perry, John Cornyn, and certainly George W. Bush.

In 1988, after Leininger’s company lost liability insurance, he founded his first PAC, called Texans for Justice, to advance the tort reform movement. That same year, 1988, Karl Rove seized on the opportunity to saturate the Texas Supreme Court with right-wing judges. Now, Rove was the architect of the watershed “Clean Slate ‘88” Texas campaign, which won conservative candidates all six of the state judgeships that were on the ballot that year. So six out of a total of nine.

Adam: So in 2005, PBS Frontline did a documentary on Karl Rove called The Architect and they really did a good job showing how Karl Rove views the media, thus the fact that we’re talking about him on Citations, used the media specifically 60 Minutes to effectively paint the Democratic Texas Supreme Court is being on the take from quote-unquote “trial lawyers” who are seen as corrupt. Now, of course, the billionaire backers of Karl Rove and the other side of the equation aren’t mentioned in the 60 Minutes report but similar how teachers unions became this all encompassing evil, but the other guys somehow were not sort of, the billionaire backers were these non-conflicted goody two-shoe philanthropists. So I want to listen to that clip right now. I think it does a good job sort of summarizing what was really at stake with tort reform in Texas.

[Begin Clip]

Man #1: He attacked, attack, attack was sort of the model that he used.

Reporter: And in the mid ‘80s, Rove found an anger point that could unite voters statewide: tort reform. To Rove, tort reform was a simple story. The elected State Supreme Court had been bought by wealthy Democratic personal injury lawyers.

60 Minutes: Is justice for sale in Texas?

Reporter: A story was pushed to the news magazine 60 Minutes.

60 Minutes: The Wall Street Journal has called the decision of one Texas court a national embarrassment. The New York Times —

Man #2: It was an enormously powerful piece in Texas. Rove was a part of the business effort that encouraged 60 Minutes, that fed them information. You couldn’t have written a headline that was better than the 60 Minutes piece or more effective.

Reporter: Rove capitalized on the story.

60 Minutes: Justice Ted Z. Robertson once took $120,000 in campaign money from Clinton Manges and then switched his vote back and forth in a crucial case involving Manges. This year, Robertson’s taken over a million in contributions from special interest lawyers.

Man #2: He knew intuitively you had to have, as Mark Twain says, a devil for the crusade. And if this was the crusade, in the context of a judicial race, which no one really cares about, you had to, you had to demonize somebody, in this case, you it was central casting, they were doing it to themselves.

Reporter: And Rove’s strategy had a bonus. If he shut down the trial lawyers, he would cut off their money to the Democrats.

[End Clip]

Adam: So yeah, again, it’s not as if they weren’t taking money from trial lawyers but it was a fraction of what the other side of the equation was. This is something you come up against time and time again. So it’s like, people say, ‘Oh, well, the New Orleans, you know, school system was corrupt, and the FBI raided them two years before Katrina,’ and it’s, like, yeah, but the other side’s also way more corrupt and that’s really not the point, right? It’s not as if trial lawyers don’t donate money to people’s campaigns but somehow the conversation only becomes about quote-unquote “trial lawyers” and we don’t talk about the fact that the other guys have dozens more trial lawyers and they also have conflicts of interest and they also fund campaigns and they also fund things like ALEC and all these bogus think tanks.

Nima: And there’s a larger movement-building piece of this, too. So part of tort reform is also about changing the nature of the courts themselves, of marginalizing and scandalizing judges that stick up for individuals and for consumers and packing the courts instead with right-wing, pro-business zealots who protect corporations from the people, not the other way around. This is a concerted effort that Rove drove in Texas in the ‘80s.

Adam: And Karl Rove played to this popular thing against tort reform, but what they never say is that these misconceptions about tort reform, misconceptions he himself just repeats, again, are not the sort of organic populist things that sort of emerge. They’re not these cultural forces that come out of nowhere like the blues or folk music, they are top down propaganda campaigns in a very sort of clear way. Propaganda campaigns that even supposed liberals begin to internalize.

Nima: So having really been born in Texas, all of this really came to a head during the governorship and then subsequent presidential campaign, and then the unfortunate administration of George W. Bush, who really used tort reform and in effect the downsizing of civil courts as a signature campaign talking point and concern. He, on numerous campaign calls during his reelection campaign in 2004, called medical liability, for instance, quote, “the largest cost in the healthcare system,” which is patently untrue. So now that that had reached the mainstream and to the highest echelons of government, we can see how this myth of the overbearance of tort on the legal system really has much wider implications for a right-wing power-building project.

Adam: So in the 1980s, certain political elites developed a full-fledged machine to implement tort reform. In 1986, we saw the creation of the American Tort Reform Association, or the ATRA, a corporate syndicate looking to overhaul civil liability laws. This followed a period that’s been called the “asbestos wars,” where some 20,000 lawsuits were filed against asbestos maker Johns-Mansville. ATRA is funded almost exclusively by Fortune 500 companies — oil, gas, tobacco, Philip Morris, Dow Chemical, Exxon, General Electric, Aetna, GEICO, many, many insurance companies as well.

The ATRA created a number of astroturfed groups relying heavily on phrases like “lawsuit abuse” to sell a narrative that “frivolous lawsuits” were running rampant. These included: Citizens Against Lawsuit Abuse, the CALA. CALA plastered billboards across South Texas with slogans like “Lawsuit Abuse: Guess Who Picks Up the Tab? You Do.” The founded a group called Stop Lawsuit Abuse. They founded a group called Lawsuit Abuse Watch. The Michigan chapter of Lawsuit Abuse Watch hosted a, quote, “Wacky Warning Label Contest” in 2007. The contest was meant to demonstrate how, after being sued, companies had to make warning labels on products extremely specific and/or clear. Examples include: “Danger: Avoid Death” on a tractor, “Do Not Iron While Wearing T-Shirt” on an iron-on t-shirt transfer, “Caution: Safety Goggles Recommended” on a letter opener. And so again, this is part of this cultural war they’re doing where you need to kind of trickle down these, this image of the legal system run amok and, of course, it’s all funded by DuPont, Dow, tobacco companies.

Nima: Right, and so you see these kind of cultural products like the Saturday Night Live ad happy fun ball with the outrageous warnings that are put on that but what’s behind that, what is making us laugh is actually bankrolled oftentimes by these major corporations. We’re just falling for it.

Adam: Yeah, because if they were organic, cultural forces they wouldn’t need to spend millions and millions of dollars going and finding these cases and bringing them to the mainstream press. And so, a 2012 Wall Street Journal editorial called California Suing cited an ATRA report on quote-unquote “judicial hellholes” to malign state court systems for their, quote, “frivolous lawsuits” unquote. The ATRA judicial hellholes report that they release every year, New York Times criticized it in 2007 for basically just being a series of anecdotes. It’s not an actual study, there’s nothing systemic or methodological about it. It’s just doing what most of these groups, what Committee for Federal Budget Responsibility does, where you sort of just create collateral for reporters who need to report something, right? ‘A recent study by a trade group,’ blah, blah, blah and of course, they always come to the conclusion that there’s this rapid effort to sue people. Now the US Chamber of Commerce, which of course is not a federal agency, although a lot of people think it is, it is a business trade group founded in 1912 that has been a major, you may be surprised to learn, has been a major driving force behind tort reform. The Chamber of Commerce founded its own tort reform group in 1998, called the Institute for Legal Reform or the ILR, which created a campaign called Faces of Lawsuit Abuse that still does YouTube videos today that garner about 115 hits per video.

Nima: (Laughs.)

Adam: Let’s listen to one of those.

[Begin Clip]

Woman: The face of lawsuit abuse isn’t rich or poor, young or old, male or female. It isn’t one particular ethnic group. It is all of these and more. Each year lawsuit abuse turns countless American dreams into nightmares. Now, a new study ranks all 50 state lawsuit systems. Where does your state rank? Go to instituteforlegalreform.com to find out and raise your voice for change. Find the power, stop the abuse.

[End Clip]

Adam: In 2009, the Chamber of Commerce began airing trailers before movies that talked about lawsuit abuse and those trailers would highlight sort of absurd lawsuit abuse cases, again, feeding this cultural, you’re just constantly inundated with this assumption that this is a very common practice. So they find these somewhat obscure cases, present them in the least generous way humanly possible, so for example, there was a case that they love to talk about where the headline is a lawyer sues another lawyer over too firm a handshake, right? And they talk about this all the goddamn time. So this is a case between two men in Palm Beach, Florida, over a 2014 handshake between two attorneys George Vallario, Jr. and Peter Lindy. Again, this is sort of like the PC stuff where at first glance, you’re like, ah, that seems kind of absurd, and then you read it, you find out okay, the guy who is being sued was 16 years his Junior. One was 60 years old, one was 76. The man who was injured was 76 years old. He, according to his statement, says, quote-unquote, he has had the “the worst pain he had ever felt” and he wakes up every day in pain. Vallario said he has gone to specialists and endured lost time and suffering as a result of the injury. He was treated by orthopedic doctors three times a week for six months, but the treatment really didn’t seem to work. And so you know, the guy is 76 years old and if the guy crushed his hand, according to him, he asked for an apology and didn’t get one which is why he sued. Now, does that merit a lawsuit? I don’t know. But if someone just sort of crushed my hand and refused to like, help me with the doctor’s bills, I think I would maybe sue them.

Nima: And yet all we hear are the headlines, right?

Adam: Yeah. And this is true for almost all these cases, right? You have this very superficial headline that really doesn’t explain the sort of nuance of it and the nuance doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a justified lawsuit or one you would even agree with if you’re a jury, but it kind of takes the wind out of the sails, right?

Nima: But then you see the faces of lawsuit abuse videos doing these, you know, man and woman on the street interviews in cities across the country and bearing the title, “This Frivolous Lawsuit May Give You A Brain Freeze”, obviously it ice cream related lawsuit hilarious, or a video called, “Take One: Can You Guess the Fake Frivolous Lawsuit?” It’s like a quiz show, a traveling quiz show, but the people who are interviewed here clearly have bought into the narrative that we are all sold, it really is not their fault, they’re given an option of a few ridiculous sounding lawsuits and then they comment on why this is a problem.

[Begin Clip]

Man #1: It honestly doesn’t surprise me these days, just with the amount of stories out there and stuff you always hear about those kinds of things out there.

Woman #1: It’s not necessary.

Man #2: Not necessary.

Woman #2: Not necessary. It raises the cost of other things because of insurance of lawsuits.

[End Clip]

Adam: So yeah, so they interview these people on the street who all have these kind of, again, very pop notions of how lawsuits work and so they say, ‘Well, you know, the stories and stuff’ and it’s like, well, what stories? Where? This is just it’s just a thing we all sort of agreed was a thing after decades long propaganda. To be fair, there was one sort of pop cultural pushback on this, which was an HBO documentary called Hot Coffee, which we will link to in our show notes. Definitely watch it. This is what we’re doing is sort of, a lot of this is covered by Hot Coffee. So definitely watch that. It was a film that really pushed back against a lot of this bullshit.

Nima: So the case that Hot Coffee is about is the now-infamous Liebeck v. McDonald’s Restaurants.

Adam: The ultimate pop tort, the original pop tort.

Nima: Yeah, the one that everyone knows about and refers to, the landmark case that occurred in 1994 about an incident that happened in 1992 and it was this: Stella Liebeck suing McDonald’s — over what? — spilling hot coffee on herself. When that obviously sounds ridiculous when presented that way, right? But it is the go to example. It’s been consistently misrepresented in popular media, from Jay Leno monologues to obviously Seinfeld to Toby Keith songs. But here’s the story. Stella Liebeck, who was 79 years old at the time, accidentally spilled McDonald’s coffee on her lap one day in 1992 when she was sitting in a car. The coffee, the temperature of which was estimated at 190 degrees Fahrenheit, caused horrific third degree burns on her legs requiring skin grafts surgery. Initially Liebeck only wanted McDonald’s to pay her medical bills totaling roughly $200,000. McDonald’s declined offering instead $800 only leaving Liebeck with really no choice but to sue the corporation. Now while the jury agreed that Liebeck should get nearly $3 million, $2.9 million, a number that got a massive amount of media attention itself, Liebeck eventually settled for about $500,000 or $600,000 and McDonald’s in turn agreed to lower the temperature of its coffee. But Liebeck’s case, despite the actually very reasonable details, that she wasn’t driving a car at the time, she was actually sitting in the passenger seat, the car was parked, all of these things got completely mangled in the media, and the case really took on a life of its own. For instance, the St. Louis Post Dispatch in December of 1994 wrote this, quote:

Only in America. The phrase used to make us think of success — names such as Andrew Carnegie and Frederick Douglass. Harry Truman, from haberdasher to president. The man who kept a sign on his desk that read: The Buck Stops Here. Not anymore. Now we’ve got the Menendez brothers and Stella Liebeck and Bryan Fortay. America, the land of the free: guilt free, fault free and responsibility free. Blame you, blame them, blame everyone, but don’t blame me. I’m just the victim.

Adam: Now the Menendez brothers were obviously subjected to years of sexual assault, but setting that aside, yeah, that this case, the coffee case was this, kind of the ultimate Paradise Lost, the fall of the garden of, where America had lost its innocence because of trial lawyers. So and then of course, you have pop culture depictions of frivolous lawsuits, which are a very popular trope in film and television. In 1990, The Golden Girls, one of the main characters, Blanche, rear ended someone while driving the car of another main character, Rose. The person she reruns threatens to sue claiming he suffered injuries from the impact. So there was an episode of Frasier where he takes a seat while waiting at his local coffee shop and he meets with a man he assaulted to smooth things over and he threatens to sue him. There’s of course, Seinfeld where Kramer mimics the hot coffee thing where he spills coffee on himself while sneaking into a movie theater and then he later did it in another episode, where he inhales too much smoke and then he calls his ambulance chasing later Jackie Chiles. CSI: New York, there was a murder victim in one of the episodes who quote “made a living” unquote from serial lawsuits. The murderer turned out to be someone he sued frivolously. King of the Hill, the character Lucky, who was added later in the series, also makes a living off suing companies repeatedly and that’s how he got his nickname.

Nima: So from entertainment to news media, we see this being a very cultural touchstone. Reader’s Digest has actually provided tons of ammunition to the tort reform movement dating back decades, but still, in the past decade or so, they still post listicles of, you know, outrageous abuses, schemes and blunders from their Waste Book, a report on government waste, which was actually written by Republican Oklahoma Senator Tom Coburn, a longtime tort reform proponent, so they republish this in their aggregation. But we’ve all seen these headlines, right? “Burglar sues homeowner who shot him” from the Muncie, Indiana Star Press in April 2016. The AP in 2018 reported, “New Mexico woman sues hospital for resuscitating her.” Yahoo News in 2019, “Woman Is Suing Olive Garden After She Got Burnt By A Stuffed Mushroom.” Also from 2019 in NBC News, “Tennessee man sues Popeyes for running out of chicken sandwiches.” From USA Today, just this year, this past February, quote, “A man sues himself? A docket of 25 of the weirdest, silliest and frivolous lawsuits.”

Adam: Yeah, so what happens is that these tort reform organizations highlight and build listicles of these lawsuits and then they share them with the media who report them and think it’s really funny. There’s not a lot of nuance. Well, you notice this is the same with the PC stories. At no point do the people reporting these ever, that I’ve ever seen in terms of like the kind of viral NBC News, AP stuff, the local reporting does this but the actual viral clickbait reporting never actually reaches out to the people who are doing the lawsuit, they never ask them for comment, because they’re not really doing reporting. They’re repeating clickbait that reinforces a cultural assumption that people sue too much. Episode 72 on John Stossel, we pretty much covered all this but suffice to say that John Stossel has spent decades, specifically going after the Americans with Disabilities Act, which is one of the very few legal and political protections for people with disabilities but John Stossel in 2013, while he was being funded by — you guessed it — the Koch brothers vis-a-vis The Reason Foundation, he did a special called The Lawsuit Industry where he always talks about small business owners being sued by people with disabilities. In 2017, he did a segment called Parasitic Lawyers and the ADA. So you’ll notice this time and time again. They always say small businesses, small businesses pay, small businesses have to pay lawsuits, have to abide by the ADA. It’s never really about small businesses and the reason we know this is because people like John Stossel are not funded by small businesses, they’re funded by big businesses, but small businesses, which we could absolutely and almost certainly will one day do an actual episode on small business owners as this human shield for corporate malfeasance, this mysterious small business owner. Now I’m sure small businesses don’t like quote-unquote “frivolous lawsuits,” but the real power center, the real people funding this are not small businesses, they’re basically all Fortune 500 companies.

Nima: Now, something that is most often missed in any discussion of tort law, is often how it is the only way that people can actually seek justice. Now, we’ve talked about this before, but it actually has a lot to do with racial and economic discrimination. So for instance, when it comes to medical malpractice, racial and ethnic minorities often get far worse medical treatment by the healthcare industry than other people, right? And are subject to many more higher rates of preventable medical errors. When you curtail the rights of patients who have been harmed or injured or even killed due to medical malpractice, this inevitably, some might say deliberately, but certainly disproportionately hurts racial and ethnic minorities. Now, this is no small thing. It has been reported time and again, that medical malpractice is the third leading cause of death in the United States. It harms more than one in ten patients and many of these mistakes are totally preventable. This is not some small thing that is blown out of proportion and as we already discussed, the idea that non-economic damages disproportionately hurt people who are either too young to be working, too old to be working or cannot work or don’t make that much money, this really has a extremely outsized effect on them. Also, when assessing damages, courts often rely on economic data that has already been generated through a very racist and classist system. When determining what kind of damages on lost salary in the future a plaintiff can get if they win their lawsuit, it’s another situation of like, garbage in garbage out, where they are looking at, you know, women get assessed at much lower rates, children who are Latino or black get assessed at much lower rates because of what they are deemed to potentially be losing in future earnings because people of those races or ethnicities or gender may not make as much in the past, and therefore they’re not assessed to make as much in the future.

Adam: One of the more infamous cases of moral panic that was actually kind of somewhat corrected by the media, there was a woman in the Upper East Side, who in 2011, was given an a quote-unquote overzealous hug from her nephew and she broke her wrist and so she sued her nephew for $127,000, which was the technical means with which she had to sue him to get the insurance to cover her losses. Her nephew and her nephew’s family supported her and thought it was a good idea. It was a sort of formality to get the insurance money. But this didn’t stop everyone from New York Magazine to The Daily News to the Washington Post to BuzzFeed having these sensationalist headlines about a woman suing her nephew after she was injured during a hug, right? Which seems outrageous. Why would you, how do you sue a 12-year-old?

Nima: Right.

Adam: So CNBC, “Aunt sues nephew for $127,000 over enthusiastic birthday hug.” BuzzFeed, “A Woman Unsuccessfully Sued Her Young Nephew After She Was Injured During A Hug.” Washington Post, “Aunt loses lawsuit against 12-year-old nephew who broke her wrist with a ‘careless’ hug.” And then of course, you look at the fine print and then she went on The Today Show and defended herself and says, ‘I have to sue to get the insurance money,’ and that the nephew and in the nephews family is totally okay with it and it makes sense because it’s a legal formality. Her insurance only offered her a $1 compensation before she decided to sue, and she wanted someone to help cover her injuries. So again, you have this, there’s this headline that seems shocking and outrageous, and of course, we all know that only 40 percent of people actually read past the headline, and then the articles don’t actually mention the nuance either, a lot of times, and then you have the reality of what happened and your reading and say, okay, well that actually kind of makes sense. And you see this time and time and time again, with pop torts, the sensationalist headline, which again is the whole point of it, right?

Nima: Right.

Adam: Because the goal is not to convey information; it’s to create little McNuggets of pop wisdom that people can say, ‘Oh, it’s like the aunt who sued her nephew. Oh, isn’t that fucking hilarious? People always want a free payday.’

Nima: And to create collective anger at the system in order to change it in favor of corporations.

Adam: Right, because people believe their insurance premiums are high because of frivolous lawsuits and so they don’t direct their anger at the insurance companies raising their premiums, right? Or, I don’t know, a system that doesn’t have a single payer healthcare system, they direct their rage at these one-off kind of Welfare Queen tropes.

Nima: So much of this has to do with the fact that our system does not actually provide healthcare for its citizens by just the nature of people living here, citizen or not. And so many of these lawsuits have to do with getting insurance money, paying for medical bills, for paying for living expenses while not being able to work in a system where prices go up, where rent is out of reach, all of these things have everything to do with the way that we are expected to live and then what happens when things change and there are no safety nets to catch people and so the legal system winds up being the last bit of recourse and then that is condemned as being frivolous.

Adam: Yeah. And there’s again, there’s this moral dimension to it that we sort of, we hearken back to this time in the ‘50s when men were men and worked and we didn’t take handouts and suddenly everyone’s looking for a quick payday, a quick get rich quick. And again, it plays into this kind of slightly fascistic nostalgia for this time in which we all worked and now we’re all just a bunch of lazy ingrates and we’re overly litigious and again, the constant barrage, the pop culture references, the John Stossel specials, all those sort of pop torts in pop culture, all the top ten, this begins to really shape how people view this and all nuance is lost because on the trial side, except for things like maybe Hot Coffee and the occasional corrective article on page B12, there’s not really a counter-propaganda effort. I think there’s been some effort to correct that, but mostly there isn’t. You really get one propaganda effort and it’s always on the side of corporate lawyers.

Nima: To discuss this more we’re going to be joined by Joanne Doroshow, Founder and Executive Director of the Center for Justice & Democracy at New York Law School. She is also co-founder of Americans for Insurance Reform. Joanne will join us in just a moment. Stay with us.

[Music]

Nima: We are joined now by Joanne Doroshow. Joanne, thank you so much for joining us today on Citations Needed.

Joanne Doroshow: Sure. Thanks for having me.

Adam: So at the top of the show, we detailed the propaganda origins of so-called tort reform from the think tanks to TV shows to popular public consciousness and, and this sort of general idea that the US is full of greedy jerks looking to kind of sue anyone for a quick buck. Now, I happen to agree that the US is full of greedy jerks, I just think they’re mostly on Wall Street, they’re not getting run over by cars and this kind of cemented itself into becoming conventional wisdom. There’s a broader media campaign, you had episodes of All in the Family, The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, you had all these sort of pop culture examples of it — for some reason, TV writers and cheap clickbait editors love these pop torts — when in your imagination or your experience did this kind of conventional wisdom cement itself and was this myth that Americans are kind of uniquely litigious and lazy and greedy, is that something that was always the case or do you think that was, at what point ‘70s and ‘80s do you think that really kind of cemented itself as this thing we all sort of agreed was real?

Joanne Doroshow: Yeah, well, it was a very orchestrated effort, actually and it all started really with the insurance industry. When we’re talking about the property casualty insurance industry, that pays claims, basically, when businesses do bad things, or doctors are negligent and it’s a very cyclical industry in terms of when rates go up and down and they decided to raise rates on primarily doctors in the mid ‘70s. That’s when it all first started, and you know, had nothing to do with claims going up. It was entirely about other accounting practices that they had, but they raised rates, they went to lawmakers, they said ‘Don’t look at us, it’s all those lawyers and juries that are forcing us to raise rates on businesses and doctors’ and there wasn’t a lot of education, and there still isn’t among our lawmakers and regulators, about whether that’s true or not. And it wasn’t true, there was never a jump in claims. But they basically went to lawmakers at the state level mostly and said, you know, ‘Unless you strip away patients rights to go to court or the rights of defrauded or injured people to go to court and sue, the rates will never come down,’ so they were sort of threatening and certainly hoodwinking the states and a lot of them succumbed to pressure and passed the first sort of wave of tort reform laws or tort limits on people’s rights to go to court. Then rates for businesses stabilized for about a decade, and then they went up again in the mid ‘80s and it was like deja vu all over again. They went to lawmakers and they said, ‘Oh, we gotta reduce rates, the only way to do this is by passing tort limits and going after juries’ and a whole bunch of states at that point did it. Then 13 years go by, same thing happens in the early part of the 2000s and these bits of sort of rate hikes, they go on for about two to three years and everything stabilizes. But so much time passes between these crises that lawmakers don’t even remember or certainly members of the media don’t remember what was really causing it, that it’s not, it’s never litigation, or juries, or anything like that.

Adam: So in the aggregate when this began to cement itself in the ‘70s and ‘80s, there was never really a spike or increase in lawsuits.

Joanne Doroshow: There never was a spike at all. And you know, we were, and some of the consumer advocates, were certainly by the mid ‘80s, I was already working on this screaming, you know, there’s no evidence of this, and the insurance companies would lie about it and then, of course, years later, go back and look at the actual data and you can see it was, you know, they were lying. But the thing to also remember here is that while these situations were happening, the corporations and hospitals, doctors, you know, even though they were being price-gouged by their insurers, because they were told to blame juries, and they knew that they’d get tort reform during these periods, they were willing to go along with it. So instead of going after the insurance companies, they joined with the insurance companies that were price-gouging them and lobbied for tort reform and other liability limits, and that’s exactly what they got.

Nima: So much of this happens out of the public eye, like what is actually behind all of this, but what I think most of us see is the public-facing messaging, which gives this general impression that tort, in general, is this kind of wacky, silly thing—something people do for a quick buck. It’s a sitcom plot, it’s daytime reality TV, it’s a goof story on page A14 of the paper, but there are real human stakes here. Can we talk about what those are and what the real human cost is to what is known as capping tort? And where that can lead?

Joanne Doroshow: Yeah, let’s first talk about what the functions of this tort system are because you can understand what happens when you start taking away people’s rights. First of all, it’s to compensate people that have been injured through no fault of their own, but through some kind of corporate negligence and sometimes these are catastrophic injuries. The second thing it does is it provides deterrence in terms of wrongdoing. It basically says to corporations, you’re going to be on the hook for liability unless you clean up your act and become more safe and that function has been so important since basically the Reagan administration when the regulatory system started to get dismantled, and there was no sort of government check on a lot of misconduct so the tort system actually provided that. So there’s that deterrence function. And there’s also a really important disclosure function because public trials will force information out into the public so that people know about it and regulators know about it. And, you know, there are many, many examples of how important those functions are and some of them, for example, listeners may know about them from movies that have been out in the last several years. Like there’s one that’s out right now, I think you can get it on pay per view called Dark Waters.

Nima: Mm hmm. Sure.

Joanne Doroshow: Which is about the DuPont poisoning —

Nima: DuPont with Mark Ruffalo, yeah.

Joanne Doroshow: Right. Well, you know, when that story was starting, it was really the lawyers or one lawyer and then other lawyers who started suing and as a result of the case, thousands of pages of testimony and depositions were released and, you know, sort of came to light and it was through that process of legal discovery that so much information was uncovered about what DuPont was doing. So —

Nima: Basically poisoning the entire planet.

Joanne Doroshow: Exactly, and who even imagined, but that’s exactly what they were doing and continue to do. So you know, that’s an example of how litigation can be so important. Another really important example a few years ago, General Motors, it came to light that General Motors had for decades before that been using a part, an ignition switch that was defective and was causing power loss, it would just deactivate critical systems like steering and brakes and airbags and all these people were hurt in these crashes and killed and GM covered the whole thing up. And it wasn’t until there was a lawsuit by the parents of one of the victims who had passed away, their daughter, Brooke Melton, that the world learned of this and all the credit goes to their attorney who was incredibly persistent. His name was Lance Cooper and during this discovery process, he hired his own engineer to prove the existence of this defect and until he did that, nobody knew about it. And then finally, GM admitted it and confirmed the whole thing. There’s a huge coverup that went on for a long time. So you know, that’s kind of another good example of how important litigation can be to uncover wrongdoing and then to hold these companies accountable.

Adam: So one of the things that strikes me is the idea that the popular misconception I think is based on kind of two things. And I want you to sort of riff on these two concepts, if you can, and tell me to the degree to which you think these are problems. Number one, there’s this thing where, because we’re saturated with plaintiff’s attorney advertisements on daytime TV, that they’re more visible and they’re seen as being sort of sleazy, they’re kind of out trolling, you know, ‘if you’ve been injured on the job,’ so there’s kind of this, but we don’t interface with Exxon Mobil’s lawyers, right? Like, there’s, like, 50 guys in suits, who play golf and smoke cigars and drink scotch together, you know, whatever, and we don’t see that side of it. To what extent do you think the kind of outward facing nature, just by the ways in which liability law works, I assume because, you know, people don’t necessarily know when their rights have been trampled, to what extent do you think that that lack of visibility, you know, that the assumption, I’m sure if you polled a hundred people, and you asked them what percentage of lawyers are what they would call quote-unquote “ambulance chasers,” I’m sure they would say 50 percent or something, right? To what extent do you think that informs or misinforms people? And the second thing is, I think people really think that there aren’t already filters for quote-unquote “frivolous lawsuits,” because of course, there are frivolous lawsuits, right? But the thing is, there are systems in place for that, because there’s a jury, right?

Joanne Doroshow: Checks and balances. Yeah.

Adam: Like, that’s the thing. The idea that there’s these 12 dupes you find who, you know, so can you kind of touch on both of those concepts and sort of talk about the misconceptions around that?

Joanne Doroshow: Yeah, well, you know, lawyer advertising, the bar associations never used to permit it and then they started and that’s why you see ads on television and what it does is actually allows people who have been hurt to figure out that they actually have their rights, there’s somebody to protect rights and they can sue. But yeah, you don’t see corporate lawyers doing that kind of advertising.

Adam: Because they don’t need to because Exxon already knows their rights.

Joanne Doroshow: Exactly and that sort of, unfortunately, will contribute to, most people don’t think they’re ever going to get hurt, and that they’re ever going to need a lawyer and they don’t, I mean, very, very few people file lawsuits unlike sort of conventional wisdom. It’s extremely rare that somebody would even file a claim for compensation, let alone a lawsuit. But I think people think that advertising may encourage people to file frivolous lawsuits. Now there are two really strong checks to the system. One is the way lawyers get paid. They get paid on contingency. That means that they don’t get anything and unless they win their case and then they take a third. There is a strong incentive for attorneys to not bring frivolous cases, because they’re never going to get a dime if they do that and, you know, these lawyers have to put out all the costs up front. It’s very expensive in some situations to bring a lawsuit so they are pretty rare. And then the second thing is, yeah, there are juries but even more importantly, there are judges and judges will knock out a frivolous lawsuit and they do it all the time and there are sanctions for lawyers to bring frivolous lawsuits. There’s a federal rule about it. It’s called Rule 11. The states all have rules about it. So there’s all kinds of checks and balances in the system to make sure that those kinds of cases don’t go forward. And, honestly, except for sort of rhetoric about this, I’ve never seen a single sort of data point, statistic from anybody in the corporate side to show that there are too many frivolous lawsuits. It just doesn’t exist.

Nima: So one of the things you’ve written, Joanne, is about the racist subtext of tort reform, something usually not talked about when this topic comes up. In your paper, which was called “The Racial Implications of Tort Reform,” you write that, quote:

Minorities are frequently forced to bear a disproportionately large share of this country’s health and safety problems. Whether it is inferior medical care, infringed civil rights, environmental pollution or any number of other indignities and injuries that juries are asked to evaluate every day, our civil justice system provides an essential tool to combat injustice in America.

Tort reform has a troubling and disproportionate effect on racial and ethnic minorities who have been injured and seek justice through the civil courts.

End quote. Can you expound on this and potentially specifically in terms of how tort reform has been messaged over the year namely, in the ‘80s and 1990s. How was the concept kind of racialized to serve as almost this quasi welfare queen narrative that we see today?

Joanne Doroshow: Yeah, I mean, the narrative is that people don’t take responsibility for their lot in life, for things that they do wrong and so they find greedy lawyers who would be willing to abuse the legal system just to take advantage of it and get money out of it. And it is sort of one of the underpinnings of the tort reform movement that we have to make it less of a jackpot, let’s say, for people because we have to make sure people take responsibility for what they do. And then of course, when you cap damages, it’s the corporations and it’s the wrongdoers that are getting off the hook here. But yeah, I mean, in terms of sort of the victim mentality and, you know, you mentioned sort of welfare queens, the others, people that are looked down upon by other Americans, some of the tort reform messaging sort of picks up on some of the anti-victim feelings that some people have about their fellow Americans and when people get hurt, it’s pretty astonishing to see that oftentimes it’s the victims that get blamed for that instead of the person that conducted the wrongdoing. So that sort of feeds into that narrative. But you know, there are other issues when it comes to medical malpractice, and the problem of substandard care in urban areas and there are high rates of preventable medical errors in some of these areas. So when you make it more difficult for people to go to court and sue, or limit what their compensation is, those who are receiving substandard care are going to be harmed by that, more harmed by, you know, a corporate CEO in Greenwich, Connecticut, let’s say, and the other related problem is the most common tort reform is what’s called a cap on non-economic damages. Those are the kinds of injuries that are suffering trauma, blindness, permanent disability, and they are not tied to one’s income. They are not economic damages. That’s what economic damages are. So economic damages tend never to be capped but non-economic damages are. So when you have somebody who’s a minority, a child, a senior citizen, women, often who don’t work outside the home, those people are more likely to receive a greater percentage of their compensation in the form of non-economic damages.

Adam: Right.

Joanne Doroshow: So, it can have a really disproportionate impact on those types of people.

Adam: One of the things is also in addition to sort of the racial aspects of it is you touched on the gender aspects and I want to talk about that for a second because I think much of what we know about, you know, a lot of the #MeToo cases from Harvey Weinstein to Roger Ailes at Fox News, like a lot of that came via lawsuit, we wouldn’t really know much about any of it if there wasn’t a lawsuit. Can we talk about the degree to which, because I mean this this sort of falls under the general umbrella, which is that we basically, the average person has basically no tools to hold corporations accountable, right? I, Adam Johnson, have no access to a lobbyist, I have no access to a congressman, that the only real tool the average person has and correct me if I am mistaken, is some sort of lawsuit, is legal restitution. Can we talk about how I think a lot of people don’t really realize that that’s the kind of function of that system and you saw this, I think, manifested quite clearly with the power asymmetries of a lot of the serial rapists and abusers that were revealed by #MeToo.

Joanne Doroshow: Yeah. Well, yeah, there’s actually a very troubling development in the ability of #MeToo survivors to bring their court cases, which are very important. They are the reason why so much of this has come to light but what we’re finding out is that most employees these days, particularly for a corporation, like Fox, let’s say, have been forced to sign arbitration clauses so that they are only allowed to litigate their case in a rigged arbitration system that is secret. That is where there’s really very limited right to appeal, where the arbitrator doesn’t even have to be a judge, can issue an opinion or make a ruling that violates the law, and there’s nothing anybody can do about it. But the main thing is that they’re secret and private. In the case of Gretchen Carlson, for example, who is portrayed in Bombshell the film and many people know her story that she was the first of the Fox employees to sue and she at first tried to sue or thought about suing Fox, but she and everybody there had signed an arbitration clause. So she went after Roger Ailes personally, and that’s how she was able to get around it but then they ultimately settled with her and she was forced to sign a nondisclosure agreement and that’s the other part of this is the secrecy problem in cases like this. She’s now working really hard both to get rid of forced arbitration, which is very difficult because the US Supreme Court has basically allowed it and allowed it to spread into almost every part of our lives now, and she’s tried to get rid of these non-disclosure agreements but she can’t even talk about her case, because of all this.

Adam: Because I mean, it seems like my other job is I write for a criminal justice reform website called The Appeal and one of the things I keep coming up against, because I’ve done various articles and podcasts on abuse of prisoners in the prisoner healthcare system, and the Angola prison in Louisiana, prisons in New York, and I keep coming across this thing called the Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1996, which to me, if you want to see what the country would look like without tort law, you would look at the prison system because they have basically no rights and as one would expect, they get treated like animals. So I think just as a sort of comment real quick, and you can comment on if you’d like or not, but I really think that if people want to see what that world looks like, by all means, go to Angola prison and see what it’s like when you have no legal recourse.

Joanne Doroshow: Yeah, and healthcare in prisons, it’s such a huge thing and, you know, talk about substandard care —

Adam: Because are they going to sue? They can’t sue anyone so they don’t give a shit.

Nima: Yeah, and what we’re seeing now, especially in prisons, and jails across the country, is this deliberately maintained petri dish where people’s rights and health are just not considered at all and almost deemed to be part of the punitive process ‘Well, you know, if you weren’t in here, then maybe you could take care of yourself,’ and so, I think we just see this kind of doubling back on itself in terms of how it damages people, the loss of rights, the loss of recourse and then subsequently the loss of health.

Joanne Doroshow: Right. Yeah, I mean, you know, you can see where the deterrent function of the tort system has been sort of voided out when it comes to the prison system for sure.

Nima: So Joanne, before we go, we would love to hear about what you are up to, what the Center for Justice & Democracy in New York Law School is doing, and how we can keep up to date and how our listeners can keep up to date on the work that you’re all doing?

Joanne Doroshow: Well, great, thanks. We just put out a huge study along with another consumer group called the Consumer Federation of America about the insurance industry, about how they create these fake crises. The reason we did it now is because we see that the industry is trying to trigger what’s called a hard market, when that’s when rates go up, for the fourth time and the insurance industry is sitting on more money than they’ve ever had in their entire history, they have a surplus of something like $812 billion, so there’s no reason for them to raise rates on anybody at this point, and they can certainly pay their claims and they’re getting out of a lot of these coronavirus claims right now. It’s interesting how they, all the events that have had to cancel, concerts and so forth are not covered, the insurance companies haven’t covered them for this. So I think they’re going to come out of this fine, you know, their investment income may be down but we needed to show to lawmakers that they have to be really worried if we see businesses and consumers getting hit with rate hikes because they’re not needed. So that’s the kind of thing we just did. We obviously are a little bit on hold at the moment but we’re also working on a project about child sexual abuse cases and, again, the insurance industry’s complicity in allowing turning a blind eye to it because we know that they settled cases over the years and never brought any of it to the public’s attention. So we feel like they have been complicit in this and we’re taking a look at that sort of thing as well. We are keeping track of President Trump and civil justice, we put out a scorecard about his civil justice record a little earlier in his term, and we’re taking a look at it again. It’s not a high priority for him as it was for some other Republican presidents like Bush.

Adam: Well, yeah, we could do a whole thing on Bush, we don’t have time, but he really seems like the center of gravity for all this and in many ways.

Joanne Doroshow: Yeah. George W. Bush was, I mean, he would talk about it almost every speech, he’d give the State of the Union, all the time and he ran on it. He ran on in Texas. He was terrible. So he made it a huge priority. This guy Trump, you know, probably because he sues all the time, doesn’t really care as much about limiting rights but that doesn’t mean people in his administration haven’t chipped away at all kinds of things, which they’ve done. So. Yeah, he’s bad news.

Nima: That is true. Well, that is I think, a great place to leave it. Joanne Doroshow, Founder and Executive Director of the Center for Justice & Democracy at New York Law School, also the co-founder of Americans for Insurance Reform. Joanne, thank you so much again for joining us today on Citations Needed.

Joanne Doroshow: Thank you for having me.

[Music]

Adam: Yeah, I guess the sort of human side of it is the side I’m interested in it because I do think some of these things become abstract in kind of debunking the myths and the propaganda machine is important, but we have to establish the stakes about why it’s bad and how corporate negligence kills people and harms people, and why it’s not just about dunking on evil corporations for its own sake, that there’s a real sort of human cost to this because corporations don’t give a shit about killing people. We have several pieces of evidence that confirm this.

Nima: We have several decades, potentially centuries to confirm this.

Adam: Yeah. So it’s like, it’s funny because it’s so stupid when you think about it but again, what especially when it comes to things like the gendered and racist effects of tort reform that I think it really kind of puts into stark view, how serious this is and why so much money goes into these pop torts in convincing people, people who would otherwise benefit from that system quite frankly, middle-class, poor people who are the most likely to be screwed over by corporate negligence, that these are the people that are more likely to say, ‘Oh, everyone else is a bunch of,’ you know, I’ve seen this in interviews, they interview people who end up suing, they’re like, ‘I never thought I’d be this guy.’ You hear that a lot. People say ‘I never thought it’d be the guy that would sue,’ and it’s like, yeah, dude, because you got fucked over and you have no recourse, it’s not a moral failing.

Nima: Right and that’s the only thing that you can do.

Adam: Right, and so maybe there’s a reason why no one sees themselves as being that guy because we are a system that views accepting the idea of victimhood or that you’ve been transgressed as somehow a failing on your part because I don’t know we’re all a bunch of weirdo Puritans, but it’s okay, bro. Don’t be so hard on yourself.

Nima: It’s never going to sound like it makes sense until it happens to you and then you start to understand how some of these systems are set up and how they’re so often set against people, against working people, against people of color, et cetera, et cetera.

Adam: Yeah, of course. And the other side of the equation never feels bad. You’ll never hear a Google corporate lawyer who’s suing for patent infringement of Microsoft, they don’t sit around saying, ‘Oh, well, people want an easy payday,’ it’s just sort of factored in and sort of how we only criticize athletes for getting big contracts, but we don’t ever criticize the owner of the basketball or football team for raising ticket prices or increasing the cost of beer and hotdogs. Only workers, only people who are sort of not part of the default structure of power, are ever said to be greedy. Whereas those who are sort of behind the scenes don’t really catch headlines, they just sort of go about their day, cutting costs, increasing risk and liability, suing other corporations, that is sort of factored in, that’s not considered part of a broader cultural moral failing, despite that being the thing that actually increased in the ‘90s and 2000s.

Nima: It also speaks to the fact that a world where a way out of precarity, a way toward survival, is deemed to be, you know, potentially like if you slip and really hurt yourself, what you can kind of get out of that, that really shines a light not on the people who are trying to actually get compensation when they are harmed, but the system in which it is then set up for people to live such tenuous lives that it seems like that is the only recourse.

Adam: Right.

Nima: So that will do it for this episode of Citations Needed. Thank you everyone, as always, for listening. You can follow the show on Twitter @CitationsPod, Facebook Citations Needed and become a supporter of our work through Patreon.com/CitationsNeededPodcast with Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson. All your help through Patreon is so appreciated, especially at this time, when we are all hunkering down, we are staying in, we are staying healthy, we are staying safe as best we can, all your help is so appreciated if you are able to do that at this time. And a special shout out goes to our critic level supporters through Patreon. I am Nima Shirazi.

Adam: I’m Adam Johnson.

Nima: Citations Needed is produced by Florence Barrau-Adams. Associate producer is Julianne Tveten. Production assistant is Trendel Lightburn. Newsletter by Marco Cartolano. Transcriptions by Morgan McAslan. The music is by Grandaddy. Shelter in place everyone, listen to Citations Needed, take care of yourself and others. We’ll catch you next time.

[Music]

This episode of Citations Needed was released on Wednesday, April 22, 2020.

Transcription by Morgan McAslan.